In the 2007 movie Shooter, Levon Helm played the scene-stealing Mr. Rate, a former U.S. military man and gunmaker who knows all the secrets of American government. He explains the intricacies of the Kennedy assassination and the absurdity of the media story that “Anna Nicole married for love” with the same mesmerizing combination of spookiness and comic indifference.

It takes great depth to know what scares people and makes them laugh. Helm, who died of throat cancer on Thursday, was a man of rare depth and maturity, and his life was a tribute to artistic bravery and spiritual pride.

The millions of people whose lives felt the touch of Helm’s creative hand will not remember him for his acting performances, of course, but for his six-decade music career. He learned to play the guitar and drums at the age of 8, and by 17 he was performing in the whiskey-soaked, smoke-saturated barrooms of Helena, Ark. Living and playing in the American south, Helm was blessed to be witness to the formation of a new American tradition: rock and roll. Elvis Presley, Sonny Boy Williamson II, and Bo Diddley left indelible marks on him.

In 1968 Levon Helm’s the Band, which started as Bob Dylan’s recording and touring band, released their debut studio album in an attempt to pull themselves out from Dylan’s shadow—certainly not an enviable task. But Music From the Big Pink not only succeeded, it also earned the Band a permanent place in rock’s pantheon. And it allowed Helm, for the first time, to greet the world with his voice—a country twang that mysteriously possessed traces of everything Helm experienced and everything that made the experience of American music: country, blues, gospel, rock … it was all there.

The glory of Music From the Big Pink, Rock of Ages, and The Last Waltz are well-known to most rock-music fans, and it is those three pinnacles of the Band’s career that will provide much of the music for memory exploration and appreciation in the coming weeks.

But his most moving moment came more quietly, with the 2007 release of Dirt Farmer, his first solo studio album since 1982. Helm had recently fought off a bout of throat cancer, and after believing he would never sing again due to the damaging effects of radiation treatments, found himself back in voice. He wrote in the liner notes, “The last few years prove to me we live in an age of miracles.”

Dirt Farmer was a comeback album in the musical, medical, and spiritual sense. It was the sound of a man not only performing music again, but living again. He dedicated the album to his parents Nell and Diamond. His daughter, Amy, produced it and sang harmony. In a creation of familial communion, Helm came full circle in his artistic and emotional life. He became the dirt farmer—toiling in the cold, hard earth for a handful of grace.

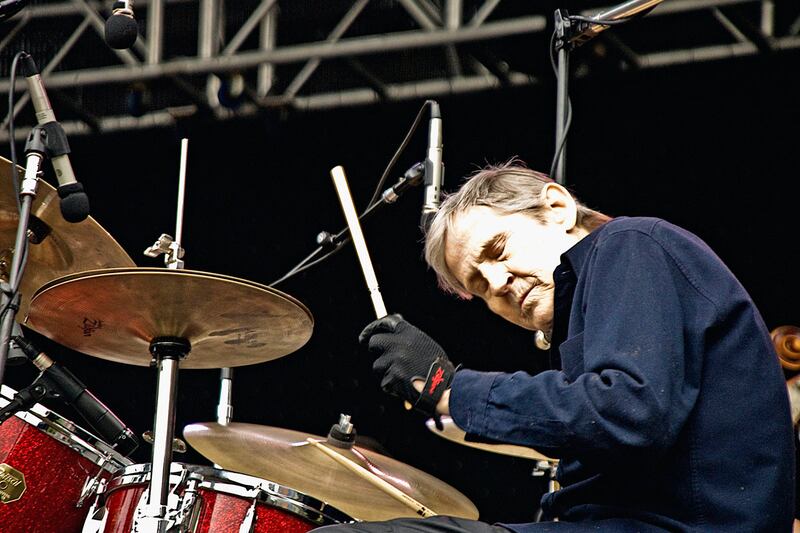

On the first song, “False Hearted Lover Blues,” Helm’s voice breaks through the door like a wheel on fire. The radiation had taken its toll, and his voice cracks and wavers on “Poor Old Dirt Farmer,” “The Mountain” (by Steve Earle), and the spiritual “Calvary,” but it always triumphs. The violins play with sweet sadness, and the harmony vocals possess the ecstasy and deliverance of a biblical jubilee. All the while, Helm keeps everyone anchored with his signature soft but intense drumming.

At the halfway point of the album comes a moment of great beauty. Helm sings a duet with his daughter on the contemporary folk song “Anna Lee,” written by Laurelyn Dossett in 2006.

The lyrics tell a story of a mother who sang her two children to sleep every night. One afternoon she heads into town to tend to her sister and dies in a drowning accident. Her children take comfort in the words of her lullaby:

I’ll return to you, dear, in the dimming of the day As the sparrow returns to her nest I’ll return to you dreaming with each lullaby Hold your sweet weary head to my breast

The prayerful promise finds its way to the children in the song of the nightingale and the whisper of an angel. Meanwhile, Helm’s rendition gives the song a mythic power filled with the secrets of the primitive heart.

Dirt Farmer won a Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album, but Helm had been offering definitive versions of Americana classics throughout his career. He sang the gospel with the fiery conviction of a Baptist minister, and he put his handprint into the foundation of rock and roll while the concrete was still wet.

Helm was a gifted musician, but his cultural significance extends far beyond his impressive body of work. He was an American archivist who sought to keep the American musical tradition alive even when it was under assault. His work and life showed that popular music can qualify as high art, both in its purpose and its effect. Rooted in spiritual and social traditions, it can be about the satisfaction of the soul as well as of the libido. It is a lesson that needs learning again.

Dirt Farmer gives listeners a profound insight into the soul of a contented man. With the memory and blessing of his parents, and with the hand of his daughter, he sang a collection of songs that spoke to the joys, defeats, deaths, and triumphs of the human condition.

On its closing song, “Wide River To Cross,” Helm sings that he is on his way home, but he still has “some miles to go.”

Helm was almost without equal as a drummer, and, considering his instrument, showcased a rare and uncanny gift for combining technical mastery with pathos. He never pounded the drums with bombastic fury, because he never needed to rely on such an easy way to move people. Bombast moves the body. Helm aimed for the heart. As the music critic Jon Carroll once said, “Levon Helm is the only drummer that can make you cry.”