Jeremy Scahill is a proud member of what the late neoconservative icon Jeane Kirkpatrick dubbed “the blame-America-first crowd.” He’s a writer, after all, for The Nation magazine and has a mutual-admiration thing going with MIT professor Noam Chomsky, who is better known for his revolutionary hatred of American power and influence than for his revolutionary advances in linguistics.

Scahill is also—to give him his due—an adventurous war correspondent who has spent much of the last decade courting danger in the Balkans, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Somalia. While his documentary Dirty Wars, based on his recently published book of the same name, is predictably scornful of U.S. motives and actions in the so-called war on terror, it is emotionally involving, a skillful piece of polemical moviemaking. It opens June 7.

Directed by Richard Rowley and co-written and narrated by Scahill, the film follows the conventions of a Raymond Chandler detective thriller, with Scahill as a hipster Philip Marlowe, discovering one disturbing detail after another until the full enormity of the conspiracy is revealed. The only thing missing is a hand-rolled cigarette.

“Kabul, Afghanistan—4 in the morning,” his weary voice confides over a sinister drumbeat, as he’s shown in the back seat of chauffeured sedan, his tense, bearded, grim face sheathed in chiaroscuro. “As an American journalist, I was used to filing stories in the middle of the night, but there’s always something eerie, driving through the deserted streets.”

And where is Scahill headed? To an MSNBC appearance, on a rooftop bathed in television lights. “Well, Keith, greetings from Kabul,” he begins. He has chosen a swashbuckling Afghan scarf for the occasion.

The film—much of which has been processed in deliberately washed-out color, frequently fading to black and white—is rife with clever cinematic devices and apparent homages to other movies. A scene of Scahill pushing a shopping cart through a Brooklyn supermarket, while narrating that “life back home was dull after being in a war zone,” seems like a direct steal from Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker. Frequent close-ups of his fingers flying across a computer keyboard constitute an update of All the President’s Men. An interview with Hugh Shelton, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff—in which the retired general clumsily defends the killing of pregnant Afghan women as “one of those damn acts of war,” because he knows what it’s like to be “shot at” by women in combat—recalls the infamous claim by Gen. William Westmoreland in the 1974 Vietnam documentary Hearts and Minds, that “the Oriental doesn’t put the same high price on life as does the Westerner.”

Rowley deftly manipulates images and sounds to get us in the proper mood. Horrific scenes of carnage and civilian funerals are inevitably accompanied by a Schindler’s List–y score played by the Kronos string quartet. Whenever Scahill is shown meeting up with various U.S. military types in darkened restaurants and other secretive locales, his stride is captured by stop-action photos punctuated by camera clicks, suggesting surveillance by an unseen government agent. And while a menacing shot of the Washington Monument against a roiling backdrop of time-lapse clouds might not remind every viewer of Saruman’s stronghold in The Two Towers, it does transform a symbol of freedom and democracy into an obelisk of the Evil Empire. And so on and so forth.

Scahill appears to revel, albeit gloomily, in his budding celebrity, mixing it up with Jay Leno on Bill Maher’s HBO show—that tense, bearded, grim face again—and testifying before congressional committees on taxpayer-funded government contractors who, he argues, are little more than paid killers. (They’re the subject of his previous book, Blackwater: The Rise of The World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army.) But the film’s relentless focus on Scahill as a counterestablishment hero-reporter, with the camera continually zooming in on his notebook scrawls as he pursues his lonely quest for truth, shouldn’t distract us from the important questions it raises about the uses and abuses of lethal force.

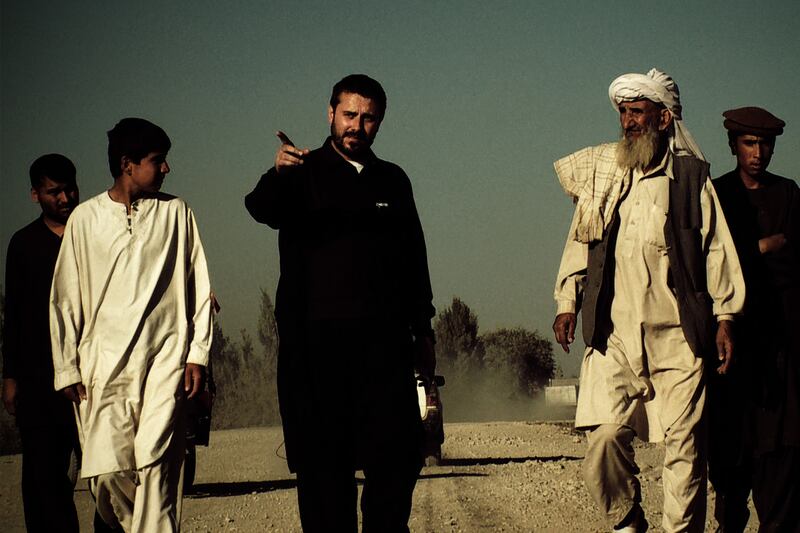

As the movie opens, Scahill travels to Gardez, Afghanistan, to interview an extended family who had been raucously celebrating a birth on a February night in 2010, dancing and playing musical instruments, when Navy SEALs descended in helicopters and shot and killed five of the relatives, including two pregnant women, for no good reason other than faulty intelligence. Instead of the Taliban insurgents they were expecting, the SEALs found an innocent family who had been bitterly opposed to Taliban rule. Among the dead Afghans was an American-trained police chief. NATO initially defended the attack (while the SEALs allegedly dug bullets out of the bodies in an attempted cover-up of U.S. involvement) and even accused the British journalist who exposed the unwarranted attack of shoddy reporting, before Vice Adm. William McRaven, the commander of the SEALs, showed up months later to formally apologize for the murders and seek forgiveness from the family.

“I wanted to wear a suicide jacket and blow myself up among the Americans,” one of the grieving men tells Scahill, saying of the U.S. special forces, “We call them the American Taliban.”

At its most illuminating, Dirty Wars exposes the heartbreaking human consequences of “collateral damage,” the obscene euphemism used by military strategists. Never mind the fog of war; the film documents the brutal, craven stupidity of war as played out in night raids of innocent Afghan families by the Joint Special Operations Command, the once-clandestine strike force that killed Osama bin Laden, as well as in the American sponsorship of homicidal warlords in Somalia, in drone and cruise missile attacks in Yemen and Pakistan, and in the summary execution of American citizens, including the 16-year-old son of al Qaeda leader Anwar al-Awlaki—a ruthless and ultimately self-defeating policy sanctioned and implemented by President Obama.

To his credit, Scahill doesn’t pretend to be an objective journalist, but nor does he seem to place much value on simple fairness. The film offers no evidence that he ever sought the explanations or insights of U.S. policymakers, whom he obviously regards with suspicion and disdain. Where other reporters might see an opportunity to develop a working relationship and obtain information, he treats a complaining phone call from an assistant to Adm. Mike Mullen, who was chairman of the Joint Chiefs at the time, as an affront and a threat.

Meanwhile, Scahill’s thumb is conspicuously on the scale during the movie’s discussion of Awlaki, whom he portrays as a moderate imam who was radicalized by American persecution and Yemeni imprisonment. He allows Awlaki’s father to assert unchallenged that his son was targeted merely for exercising his First Amendment rights to speak out against the United States—notwithstanding evidence, unmentioned in Dirty Wars, that Awlaki participated in the planning of the foiled “underwear bomber” attempt on Christmas Day 2009 to down an American airliner and was in close contact with Army Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan, who is scheduled to go on trial next month for the November 2009 shooting deaths of 13 people and the wounding of 32 others at Fort Hood, Texas. Surely images of that mass murder would have been as dreadful as any bloodbath in Afghanistan or Yemen.

Scahill, whose prose turns increasingly purple as the movie progresses (“Like a flywheel, the Global War on Terror was spinning out of control,” he narrates at one point), argues that Obama has in essence created a monster—a secret military force, with billions of dollars at its disposal but hardly any public accountability, that can project itself around the world and perpetrate terrible violence in sovereign countries that are not at war with the United States.

“We have created one hell of a hammer,” a confidential source, obscured in shadows with his voice altered, tells Scahill during a Deep Throat–ish encounter. “And for the rest of our generation ... this force will be continually searching for a nail.”