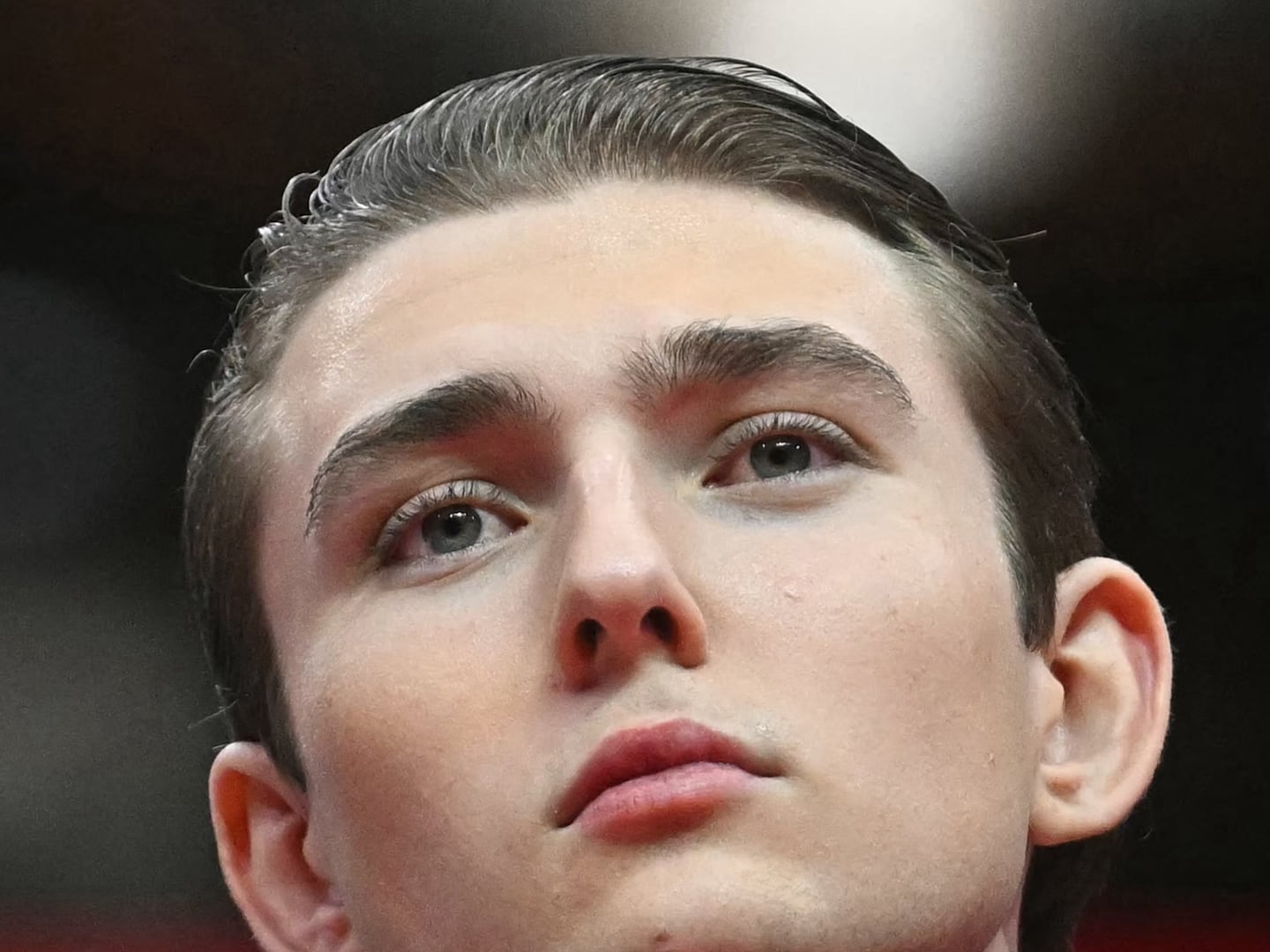

It’s around the fourth time that Jake McDorman and his The Right Stuff co-star Patrick J. Adams joke about him Zooming from his “murder room” that McDorman lets out a nervous laugh. “OK now I’m feeling like maybe this joke isn’t going to look good in writing,” he says, cringing—though still giggling—from his dark, tarp-strewn kitchen, where he’s been relegated for interviews during a house renovation. “I’m just going to put that out there.”

The teasing is appropriate. (“Keep him muted!” Adams ribs when McDorman signs onto the video call.) Adams plays John Glenn and McDorman is Alan Shepard in The Right Stuff, Disney+’s new series based on Tom Wolfe’s 1979 book and its 1983 Oscar-nominated film adaptation. About the seven astronauts whose lives were rocketed into upheaval when they were selected for the Project Mercury mission to send the first American into space, the series positions Glenn and Shepard as rivals, comrades in mission but adversaries in just about all other aspects of life.

But a sudden anxiety over how their jokes might play in the press isn’t some sort of actor’s narcissism; McDorman, who previously starred in Limitless and the Murphy Brown revival, and Adams, who spent nearly a decade playing Mike Ross on Suits, vibe on the opposite end of that ego spectrum. Rather, how the media—and then the world—interprets the most casual of comments and slightest of gestures is a dominant part of our conversation, as the stress that aspect of celebrity put the Mercury Seven under is one of the more nuanced explorations of the Right Stuff series, which launches Friday on the streaming service.

“This was really the first reality show,” Adams says. “They had to figure out how to sell this to the American public, while at the same time pulling off this extraordinarily insane and dangerous task of getting to space.”

“They faced a lot of ridicule amongst their own peers,” McDorman says, mentioning a scene in which Shepard’s father insulted him for “throwing away a Navy career to become a pop star.”

“It’s not like they were a bunch of musicians or artists or actors, who know that part of the job description is to curate some version of a public image to go along with your work,” he continues. “These were mad-dog fighter jocks. Hard-drinking people who lived on the edge, who then all of a sudden had to live up to this kind of infallible version of themselves before they had accomplished anything or even defined what an astronaut was.”

If there was one thing that director Philip Kaufman’s near-flawless 1983 adaptation of Wolfe’s novel and the astronauts’ story lacked, it’s that, even at a running time of over three hours, the adrenaline of the adventure left out some of the more meditative frustrations of the experience.

Project Mercury drafted seven of the country’s most talented fighter pilots, men so charged by renegade spirit and a sense of duty that they sometimes viewed their career’s 1-in-3 death rate as a dare more than a detriment. Each is willing to do whatever it takes to become the first man in space, yet each is oblivious to the fractured expectations heading their way. They bask in the spoils of celebrity—booze, women, freebies—but largely flinch at the responsibility of government service: they are being crafted and exploited as props for patriotism.

Some of the men, chiefly the righteous, Scout Leader-esque Glenn, see opportunity in the gladhanding. He’s game to hone a manicured image of American masculinity and morality, a packaged ideal for the country to rally around and then beam to the stars. Others, like the cocky, petulant—yet brilliant—Shepard sneer at the constraints, at best, or end up in fisticuffs in an attempt to reject them.

They became instant celebrities, and instantly at odds with the attention and the media. Enter a crisis manager and Life magazine, which is granted exclusive access to the men and their families in exchange for assistance in the other bold mission back on the ground: manipulating these military men’s intentions into an abstract of values to serve others’ political agendas and ambitions.

They were tasked to learn how to be astronauts, compete with each other for which of the seven would be the first in space, and adhere to a gee-golly standard of morality to drum up faith that America is great again, in turn returning patriotism to the country. (I can’t imagine why any of that would seem resonant in 2020...)

“Suddenly these guys were unable to do the job that they were hired to do,” Adams says. “The thing that everybody was excited for them to do, they couldn't because they were having to do interviews every day, and then take pictures, and then be running around the country going to factories on a press tour.” Then once Life is involved, “of course it's going to be everybody dressed beautifully on their front lawns with their happy families. For so long, that’s all we got to know about these guys.”

The edges that were sanded out in that process, the things that made these men human—and, in a powder keg of pressure and historic stakes, fallible—are what this version of The Right Stuff delves into. “They were expected to live up to this image that was impossible to maintain,” McDorman says.

It’s interesting to watch the show taking place in 1959 and observe how much the country and its values have changed, but how little the image it desperately clings to has not.

“Who can carry the weight of that now?” Adams says. As it happens, we’re speaking on the night of the first debate between Donald Trump and Joe Biden. “I mean we're about to watch it tonight. We're all trying to make it this guy [Biden], and God hope it works. But, you know, it's a lot for one person to shoulder. I would say probably impossible.”

Early on in the series, there’s an amusing moment when the astronauts bond over how frustrated they are with the inanity of the questions they’re peppered with: “What toothpaste do you use?” “What brand of underwear are you taking to space?” They realize they’re no longer macho fighter pilots so much as they’re fodder for banal lifestyle content.

While careful not to falsely equivocate themselves to pioneer astronauts and American heroes, there’s a semblance to that exasperation that Adams and McDorman can certainly relate to as actors.

Adams remembers when he first started Suits and was thrown into the red carpet lion’s den for the first time, ready to talk at length about his character on the show, only to be asked in quick succession what his favorite fall cocktail was and what song he couldn’t stop listening to at the moment.

“I was so prepared to talk about the job at hand,” he remembers. “It's how I feel like these guys were. They’re ready to talk about the mission, they’ll talk about you know what they’re looking to accomplish, they’ll talk about what brought them to the program. But all of a sudden they're like, ‘They want us to talk about what shoes we're wearing, or what our clothes are like, or what our wives think about things.’ You can watch the Mercury press conference and you can see them all struggling.”

There’s also the assumption that being thrust into the public eye means you’re automatically a person who would be good at navigating that space. That’s not been Adams’ experience. “Going on a talk show can be the most terrifying thing in the world,” he says. “You don't have a script. They’re like, ‘Just be yourself!’ But I don't know who myself is!”

McDorman starts laughing and jumps in. “You’re like scanning Stanslavski like, ‘What do I say on a talk show? What’s my motivation? It’s gotta be in here somewhere.’”

The Mercury Seven had Life magazine to help take the edge off. As for Adams and McDorman, circumstances have turned their press junket for The Right Stuff virtual, which has inherently made things more relaxed and seemingly manageable.

“It's a horrible time and we all wish this wasn't happening,” Adams says, grinning across the Zoom window at McDorman, “but there is sort of a nice side benefit of being able to just walk into my office or your murder room”—McDorman cringes again—“and just do a bunch of press.”