Since the first truly national armies emerged in early 17th century Europe, statesmen, soldiers, and military historians alike have seen battle as the soul of war, and the decisive battle as the chief means for securing war’s political ends. Carl von Clausewitz, the pre-eminent philosopher of war in the West, was obsessed with the idea of the sustained combat engagement between adversaries. “Battles decide everything,” he declared. “Fighting is to war what cash payment is to trade, for however rarely it may be necessary for it to actually occur, everything is directed toward it, and eventually it must take place all the same and must be decisive.”

Napoleon, whom Clausewitz called “the god of war,” had a genius for winning large, set-piece battles, even when his forces were outnumbered. At Austerlitz, Napoleon crushed Austria, and brought an end to the War of the Third Coalition. On the fields of Jena-Auerstedt he vanquished the formidable Prussians, and soon thereafter presided over the largest empire in Europe since Rome. Little wonder his campaigns are closely studied in war colleges around the world to this day.

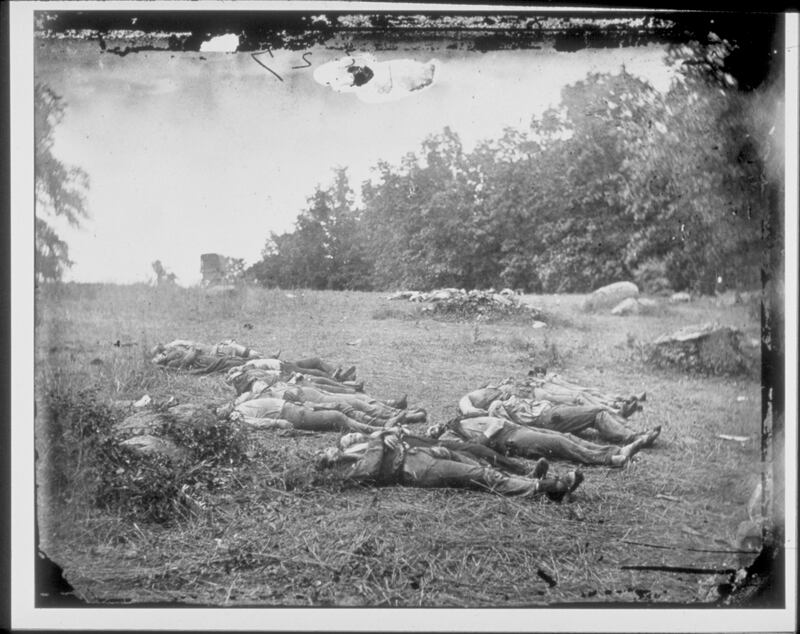

Over three days of furious combat at Gettysburg, momentum in the American Civil War passed irretrievably from the Confederacy to the Union, as Lee’s second, and last, invasion of the North was turned back. Hitler’s dreams of conquest in the east died in the grim, frigid wreckage of Stalingrad, and D-Day sealed the fate of the Third Reich in Western Europe.

Thus, the direction of history, the rise and fall of empires and nations, has often hinged on the outcome of bloody clashes of powerful armies over the course of a few hours or days.

Or has it?

Cathal Nolan, a professor history at Boston University, thinks the conventional wisdom about battles—as outlined briefly above—is pretty much all wrong. “Singular victories or defeats that created lasting strategic change” have been the exception, not the rule, in major wars since the 17th century, Nolan asserts in his provocative book, The Allure of Battle. Most of the battles historians have labeled “decisive” ultimately failed to make a direct impact on “the political outcome of the war of which they are a part,” and thus, fell short of the mark. Rather, wars, particularly modern wars among nation states, are typically won only when one adversary falls victim to “exhaustion of morale and materiel”—in other words, through the grinding down process strategists call attrition.

Moreover, says Nolan “the short-war illusion,” the idea that major conflicts can be won in a matter of a few weeks or months through one or two spectacular battlefield successes, led to the greatest catastrophes of the 20th century: World Wars I and II. It all began with Prussia’s stunning victories over Austria and France in the wars of German unification (1866-1871). Prussian Army Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke was the architect of German success. In both conflicts, Moltke executed a brilliant plan of rapid mobilization to the front by rail, followed by deep envelopment and destruction of large enemy formations.

Both wars were essentially brought to an early conclusion by overwhelming Prussian victories in early, set-piece battles: Koniggrattz led to the end of the Austro-Prussian War of June-July 1866, and Sedan to the end of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71.

Prussia’s rapid victories through decisive battle were anomalies; a few years after he trounced France, Moltke said he doubted that a newly unified Germany, or any other great power, could secure victory quickly against a strong adversary, given the advantages the latest weapons technology bestowed on the defenders, and the ability of industrial societies to mobilize vast resources for war-fighting.

But other great power military strategists weren’t listening to what Moltke said after the fact. It was what he had done that mattered. Prussia’s success did much to encourage an irrational “cult of the offensive,” and the delusion that victory in the next war among great powers would go to the army that could mount the first overwhelmingly powerful offensive thrust.

World War, I of course, proved Moltke entirely right, as the initial offensives of that war all came to grief, and the conflict settled down into a grim, stalemated, war of attrition. Yet, says Nolan, even the cataclysm of the First World War failed to kill the short-term war illusion off for good: In the ’30s, the allure of “lightning war”—a new variant of the decisive battle illusion—led the Nazis to launch a war they could not possibly win. Japan, too, fell victim to the fantasy that it could create a vast Pacific empire through a series of spectacular early victories in a war against the United States and the British.

Nolan’s book can be read as a kind of frontal assault on Clausewitz’s domination of the way Westerners think about war, and the way most popular historians write about it, i.e., with a very heavy emphasis on battles. It’s a plea to remember that battles are but one of many factors that explain how and why wars are won and lost. Grand strategy—where political and military spheres intermix—industrial mobilization and management, logistics, the maintenance of public support for the government, attrition of forces in the field—all these factors, and more, ultimately affect war’s trajectory and outcome. To focus intensively on battles is to oversimplify war’s inherent complexity.

A Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVP) is approaching Omaha Beach, Normandy, France, 6th June 1944. To the right is another LCVP. The soldiers are protecting their weapons with Pliofilm covers against the wetness. These U.S. Army infantry men are amongst the first to attack the German defenses probably near Ruquet ? Saint Laurent sur Mer. Photo: Robert F. Sargent, U.S. Coast Guard (USCG). Normandy, France.

Galerie Bilderwelt/GettyThe Allure of Battle is written with impressive energy and verve, but its core thesis isn’t exactly original. The broad thrust of the “new military history,” which began to gel in academia in the ’80s and really picked up steam in the ’90s, is that to understand war in general, or a particular war, one must get beyond the “drum and trumpets” studies of battle and campaigns to explore the culture and social institutions that shape the people who do the fighting and create the strategy. “The new military history asks us,” writes historian Peter Peret, “to pay greater attention to the interaction of war with society, economics, politics and culture.”

In Nolan’s book, one hears reverberations of Russell Weigley’s 1991 classic, The Age of Battles, which chronicles the stupendous efforts of Europe’s great powers to achieve political dominance through the promising new instrument of large, professionally-led armies from the 1630s through the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. Weigley comes to the startling conclusion that these efforts came to very little: “War in the age of battles was redeemed by no appreciably greater capacity to produce decisive results at a not-exorbitant cost than in . . . any other age. Its indecisiveness took different forms than in the trenches of World War I, or the guerrilla raids of Vietnam, and the drama intrinsic to great battles often diverted attention from indecisiveness; but recalcitrant, intractable indecision nevertheless persisted.” The age of battles, concludes Weighley, “proved to be an age of prolonged indecisive wars.”

The notion that battles carry less weight in bringing wars to their conclusion than, say, grand strategy, or logistics, or attrition, is an arresting one, and seems to be borne out in several of America’s longest and most complex conflicts. In the Revolution, George Washington was well aware of the military limitations of the Continental Army in numbers and training. He knew he could not win a conventional 18th century war of battles against the British Army. So he pursued what 20th century defense analysts call a protracted war strategy, in which keeping his army intact to fight another day was much more important in the broad scheme of things than defeating the enemy in the field.

It was Washington’s ability to hang in and to win a few engagements of limited strategic importance that rekindled Americans’ faith in the “Glorious Cause,” and convinced the French to join the war against the British. French military—particularly naval—support was not only crucial in securing victory at Yorktown. It went far toward convincing Whitehall and the King that Britain could not prevail against both the Americans and the French at an acceptable cost.

Another factor in that decision had been Nathanael Greene’s masterful campaign to wrest the Carolinas and Georgia back from British control by deftly integrating hit and run attacks by partisan bands with pitched battles fought by his own regular forces against those of Lord Cornwallis. Greene lost the pitched battles. But “rapid movement and constant pressure wore out Cornwallis,” writes historian Don Higginbotham, and he “limped northward to Virginia and Yorktown, leaving Greene to pick off one by one his isolated outposts” in South Carolina and Georgia.

Unlike virtually every other Civil War general, including Robert E. Lee, U.S. Grant lacked the Clausewitzian fixation with enveloping and annihilating his adversary in a decisive battle. He thought more broadly about ways to bring the Union’s advantages in numbers of troops and industrial production to bear in campaigns, and even clusters of campaigns, to break down the will and the military power of the South.

In spring 1864, Grant, Sherman, and President Lincoln fashioned an ingenious strategy of attrition that brought the Confederacy down within a single year. Five simultaneous strikes against the main Confederate armies and production facilities would prevent the South from exploiting its advantage of interior lines. Grant personally commanded Union forces in the Overland Campaign against Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. For months Grant hammered away at Lee’s defensive lines without securing a definitive battlefield victory. But he forced Lee’s ever-more-battered army to retreat farther and farther to the southeast.

Grant finally succeeded in pinning Lee’s army down in a long siege at Petersburg, the main supply hub for the Confederate capital at Richmond. Gradually the Union cut off all the rail lines between the two cities, forcing Lee to attempt a breakout. By that point—March 1865—the Army of Northern Virginia was too depleted and exhausted to break through two powerful corps of Union troops. And so, at Appomattox, Lee surrendered. The North defeated the South not with crushing defeats in individual battles, but through a highly effective—if costly—strategy of attrition.

The Vietnam War demonstrates dramatically how wrong-headed a battle-oriented strategy can be in a war for control over the rural countryside. General William Westmoreland’s strategy placed primary emphasis on “finding, fixing, and destroying” Communist main-force units with superior American mobility and firepower in “big unit” engagements. Meanwhile, he neglected to mount a serious challenge to the political and guerrilla warfare campaigns carried out in the South Vietnamese villages by the Vietcong.

Dangling sticks and carrots, the Vietcong insurgency was able to build a remarkably resilient clandestine government in vast swathes of the countryside. That government—the National Liberation Front—managed to recruit tens of thousands of guerrillas each year, and provide succor to the troops of the regular North Vietnamese Army, who deployed to the South in order to meet the challenge of rapidly expanding American combat forces.

General Vo Nguyen Giap, commander in chief of the Communist forces in Vietnam, was able to regulate the intensity of combat to suit his own purposes by withdrawing his regiments and divisions into sanctuaries in Laos and Cambodia. Like Mao, whose protracted war strategy he emulated, Giap understood that space and time could be greater assets that battlefield victories.

The regular Communist forces lost virtually every big unit battle they fought with the Americans, but Giap, unlike Westmoreland, believed this wouldn’t matter in the long run. By protracting the conflict and successfully portraying the American way of war as needlessly destructive of civilian life, Giap and his colleagues in Hanoi believed they could break the will of the American people and their government to carry on with the fight. Once the Americans left, South Vietnam would fall with relative ease.

They were right. The Americans gradually wearied of a destructive and inconclusive war, and pulled out all their ground forces by March 1973. South Vietnam fell apart under the pressure of a North Vietnamese blitzkrieg just two years later.

Meadow strewn with Confederate dead photographed by Alexander Gardner 2 days after fighting had ceased during bloodiest battle of Civil War.

Alexander Gardner/The LIFE Picture Collection/GettyAnd so, it has to be said: Cathal Nolan is surely right in claiming that individual battles that “fix the outcome of the war of which they are a part are rare.” But it simply doesn’t follow, as Nolan repeatedly asserts in his massive survey of warfare in the West, that most battles are little more than “accelerants of attrition,” and thus, by implication, not worthy of close attention on the part of those who wish to understand what war, or any given war, is all about.

What Nolan fails to address, and should have done in a book with a subtitle like “A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost,” is the looming presence in warfare of the decisive battle’s close cousin: the crucial battle that does not decide the outcome of the war, but nonetheless significantly alters the balance of forces—politically or morally or militarily—or leads a combatant to abandon one campaign strategy for another, or changes substantially a commander’s understanding of the war he is fighting.

By Nolan’s narrow definition, neither Gettysburg, Stalingrad, nor the Tet Offensive were decisive battles. But who can doubt that each of these engagements significantly altered the trajectory of the wars of which they were a part? Who can quarrel with the idea that in studying those battles, we can learn a great deal about the nature of the conflict at hand, about the adversaries’ strengths and weaknesses, and gain important clues as to the ultimate outcome?

It may be true, as Nolan writes, that since the days of Napoleon and Clausewitz, generals and historians alike have put too much emphasis on decisive battle, and not enough on other factors that shape war’s outcome. It’s certainly true that military historians—and their book publishers—have often called battles decisive even when they fell short of that mark.

Yet we need to guard against going too far. Battles, great and small, have an abiding and important role in explaining the outcome of wars, and the study of past battles remains enormously helpful to strategists and planners preparing to wage future conflicts. For while decisive battles are indeed rare, it’s hard to deny that battle constitutes the essence of warfare, and always has. It’s the theater of war where the character, the will, and the primal emotions of the adversaries directly collide. What happens in the collision is often unpredictable but always revealing.

Battle, writes historian John Keegan, “is essentially a moral conflict. It requires, if it is to take place, a mutual and sustained act of will by two contending parties, and if it is to result in a decision, the moral collapse of one of them.” It is in battle that we see “men struggling to reconcile their instinct for self-preservation, their sense of honor, and the achievement of some aim over which other men are ready to kill them.”

Clausewitz was engaging in a bit of hyperbole when he said, “battles decide everything.” They do not, but they are far more important in unraveling the mysteries of victory and defeat than Professor Nolan would have us believe.