Arthel Watson got his nickname one night in a furniture store in Lenoir, N.C., in 1951, when he was just 18 years old. He was by then sufficiently gifted on the guitar to be performing at what might be called the semi-pro level. A Lenoir radio station was doing a remote feed from the store, where Watson (PDF) and his cousin were performing, and the announcer, having decided that Arthel was not much of a handle for radio, asked the audience for suggestions. A woman in the audience said, “Call him Doc.” The name stuck, and he’s been Doc to the world ever since.

Doc Watson died Tuesday at the age of 89 after failing to recover from surgery performed late last week. Though plainly showing some signs of frailty in recent years, he had continued to perform almost to the end, having headlined in April, as usual, at Merlefest, the North Carolina music festival he helped found in honor of his son and musical partner, Merle Watson, who died in a tractor accident in 1985.

Doc had the good fortune to be born in western North Carolina, a region rich in traditional music. His first musical memory was being held in his mother’s arms while listening to shape-note singing in church. The Watsons were not well off, but they loved music. Doc remembered getting a new harmonica every year in his Christmas stocking starting when he was 6. When he was 11, his father built him a banjo, at first fashioning the head out of groundhog hide. When that proved unsatisfactory, and after Doc’s grandmother’s 16-year-old cat died, the cat replaced the groundhog, to much better effect.

He remembered getting his first guitar, a $12 Stella, when he was around 13. But arguably the most crucial element in his musical education was the Victrola that the family bought, complete with a few 78s, when Doc was about 6. “There was, I believe, a record or two in there by John Hurt, and the ‘Blue Ridge Mountain Blues’ by Riley Puckett.” The collection soon expanded to include music by Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers and Jimmie Rodgers. “Even though I was just a young’un,” Doc recalled years later, “I began to figure out what the blues were.”

At the age of 10, Doc, blind since infancy, went to Raleigh to attend the Governor Morehead School for the Blind. There he first heard classical music and big-band jazz. And there he discovered the music of Django Reinhardt, the gypsy-guitar genius who would be a lifelong influence. “I couldn’t figure out what the devil he was doing, he went so fast on most of it,” Doc said, “but I loved it.”

In musicians’ jargon, a player who’s particularly receptive to the genres and techniques of other players is said to have “big ears.” Nobody ever had bigger ears than Doc.

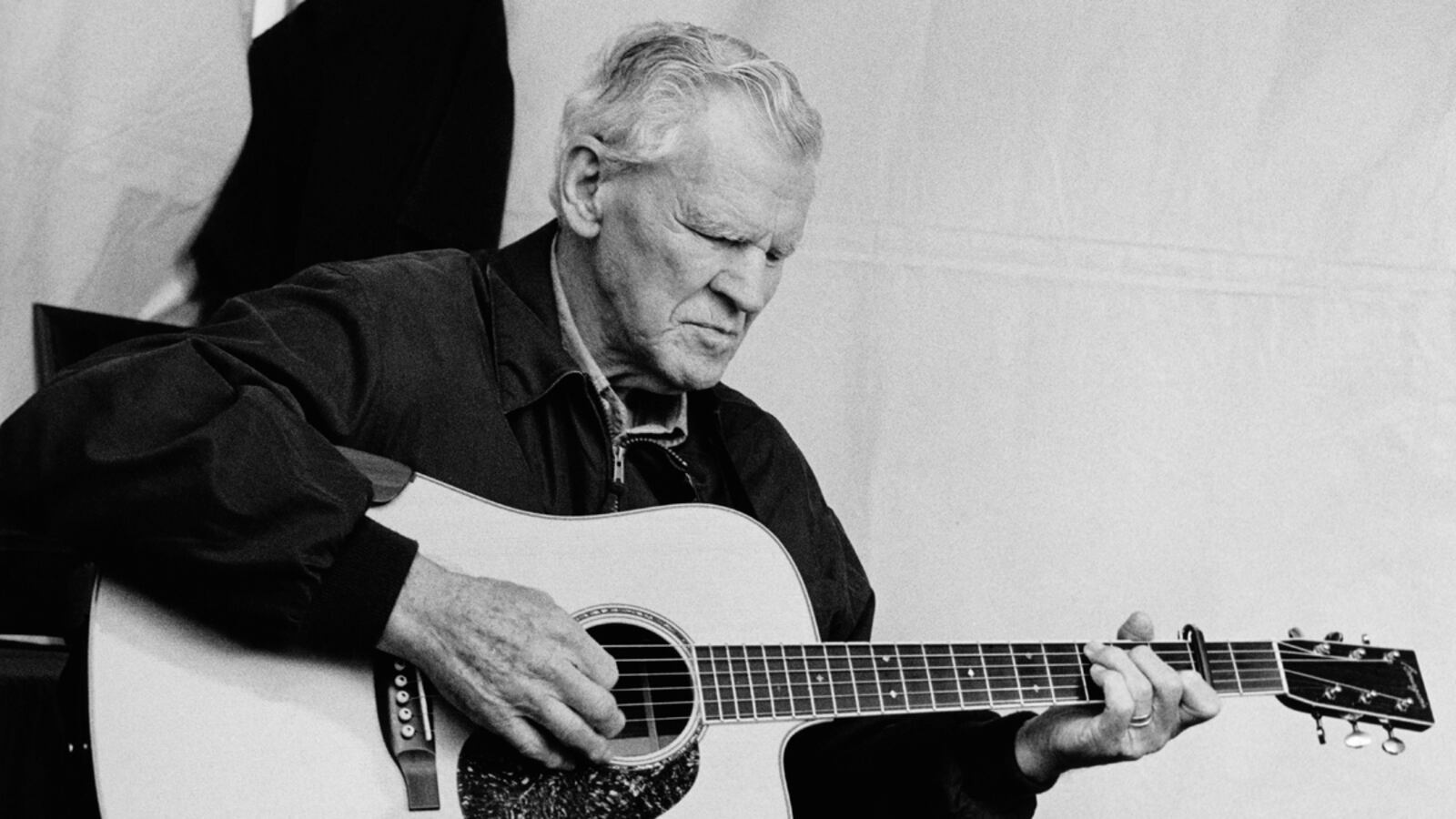

As a young man, he played in a country band where he used an electric guitar. Because a lot of the band’s gigs were square dances, Doc was called on to play the lead on fiddle tunes (the old mountain tunes that supply the core of the square-dance repertoire) on his guitar. Later he would adapt that style in his acoustic playing, and a flatpicking guitar hero was born. For a lot of players, flatpicking is merely an exercise in speed. Doc, on the other hand, while he had speed to burn, never disconnected his hands from his brain. His leads are intricate, thoughtful, and dense. Little surprises lurk everywhere, and the closer you listen, the more you hear. He may or may not have been the fastest flatpicking guitar player who ever lived, but he was surely the fastest flatpicker with the best taste.

Beginning with his early days spent playing for tips on the street, and continuing on to his quick rise to fame in the midst of the folk boom of the early ’60s and then touring for the rest of his life, Doc was traditional music’s best ambassador. But he didn’t just flatpick fiddle tunes. A consummate entertainer, he mixed them in with blues, swing jazz, old time, bluegrass, pop country hits, novelty songs, folk ballads, and standards. He could fingerpick as well as he flatpicked, and he sang with such dexterity that he made it all sound effortless.

A lot of people surely got their introduction to mountain music and the blues through Doc. He didn’t make it sound like school. He made it sound like fun. If you were a picker, he inspired you, because even if you couldn’t play as fast as he did, he was still exposing you to a wealth of material worth learning, even if all you did was strum along to the words of a song. And while his concerts certainly showcased his virtuosity, they were more like relaxed fireside jams, where the player calling the tune might play “Shady Grove” or “Deep River Blues,” and then follow it with “Summertime,” and then tell a corny joke. But a funny corny joke.

Growing up in North Carolina, I got to hear Doc play a lot. His playing was always amazing, but what I remember most clearly about those concerts is his manner. He was genial, easygoing, and always a gentleman. Living in the heart of traditional American music, you heard a lot about a lot of players, not all of it flattering. I never heard anyone say an unkind word about Doc. A gentleman is said to be someone who accords everyone, high or low, with the same dignity. That was Doc.

As a young reporter, I once got the chance to interview him before a show in the early 1970s. The only question I remember asking was “Do you still like performing?” He thought for a moment, and then replied, “No, not really.” I had no way of knowing then that he’d been performing in some professional capacity for the better part of two decades, and much of that time spent traveling alone from one strange town to another by Greyhound bus. For a blind man on his own, it could not have been an easy life. But what struck me then and stays with me now is the thoughtfulness and honesty in his answer. He didn’t have to be forthright with me, but he was, simply and instinctively. But that was the feeling you got from him, on either side of the footlights. You always felt like he was leveling with you, that he was who he was, whatever the circumstances.

One of the last times I saw him was at a music festival in Virginia, where he was sharing the bill with Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys. Doc played first, and you could hardly hear him. The crowd was full of drunk college kids who screamed and hollered through every song he tried to play. Endlessly they called for “Rocky Top,” maybe the only country song they knew. They kept it up for his whole set. When Bill Monroe came on, the din had not abated. Never a man to suffer fools gladly, Monroe stalked off the stage before he was halfway through the first tune and never came back. I didn’t blame him, but what I’ll always remember about that night was Doc’s unflappable dignity. He never felt rattled, never ceased to try to play the show he’d been hired to play. From the first note to the last, he kept his cool and tried his damnedest to entertain those who cared to listen. I won’t say he ever exactly had that crowd in his hand, but he never stopped trying, never gave up.

Doc Watson was a great Southern musician, a great American musician, a musician for the world. I can’t imagine anyone anywhere who loves music not appreciating what he played. I can imagine that he taught countless listeners to love music they might never have discovered any other way. The man and his music were indissoluble—nimble, dexterous, heartfelt, and always down to earth. And when he spoke, he made you think even while he was making you laugh.

“All music to me is universal,” Doc once said. “There’s some things I can’t relate to, but there’s a lot of things in the universe I can’t relate to either.”