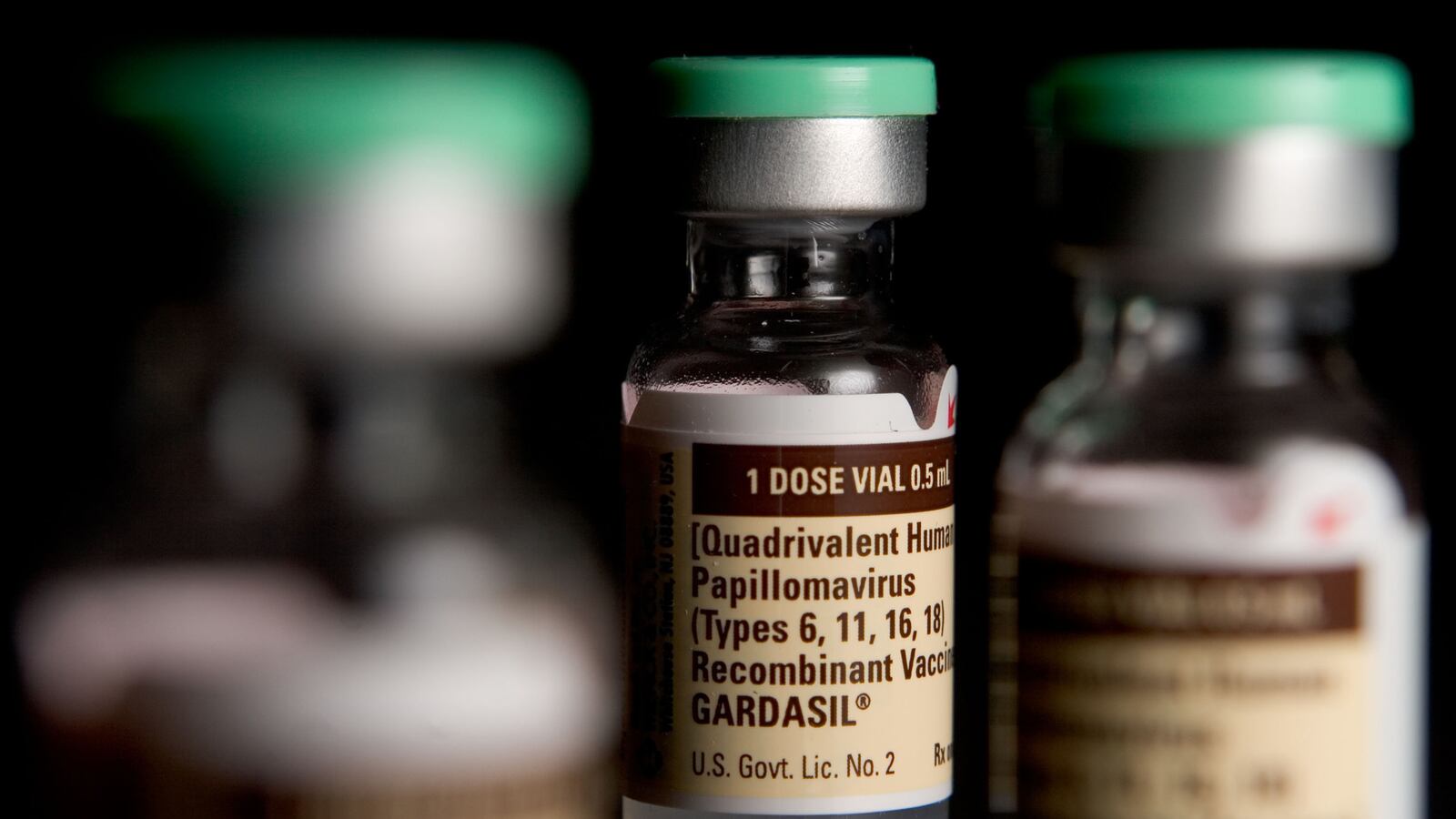

Some 200 preteen and teenage girls in a Colombian village have suddenly developed symptoms, including nausea, dizziness and fatigue, without clear explanation. The rapidity of onset has raised concerns that there might be an infection going through the town or—more sinister—that it could be a reaction to a vaccine introduced to prevent human papilloma virus (HPV).

Likely it is neither. In fact, the exact story has played out previously in another town—Le Roy, New York, in 2012—with the same age group and sex of the affected (all girls but one), and the same vaccine just introduced. There was a call from anti-vaccine enthusiasts and others to halt the vaccine ASAP until the inconvenient fact came out that, though the vaccine was indeed being given in the town, many of the teens with the symptoms had not received it. Ah, well.

Rather than a strict medical cause, many have labeled the Le Roy problem and the current Colombia illnesses as “mass hysteria” or a “mass psychogenic illness” (MPI). This diagnosis occupies a uniquely dark and uncomfortable corner of medicine. The concept of mass hysteria is rather chilling to consider. It is particularly awkward given the demographic: Almost every example is that of young girls who develop a cluster of near-identical symptoms. And, after much sturm und drang, all are diagnosed as nuts (though with gentler, more clinical terms) by older men who, let’s face it, are not without their own issues.

Who are these doctors but one-time loners, who in their own teen years were first rate in science but little else, and sat by wistfully as frisky girls first became frisky? Now as adults, they still are confused by teen girls, yet are called upon to pass judgment on the behavior of a dozen or two or ten. So their meat-handed treatment of any behavior that falls outside their narrow view of sanity and insanity always must be questioned.

Plus, there is the unfortunate fact that the word “hysteria” is derived from the Greek, hystera, for “uterus”—ergo the hysterectomy, a surgical removal of the uterus. This raises the possibility that the entire notion of hysteria is itself a completely hostile male construct, a broad category for broads, a place for guys to toss anything that makes them uneasy. Tears over a new gift; tears over no gift. Happiness and sadness in excess and at odd times. Weeping when the casserole is burnt or the mascara runs. You know, crazy chick stuff.

Further to the point: why isn’t there a male equivalent? I mean, what about teen guys who get together and paint their faces and go to football games barely clothed despite the arctic chill, then curse and yelp and blog ceaselessly and in unison about the dumb coach and the moron goalie or halfback who has ruined their life, the stupid bastards leaving them with teen bile blackening their gullet? This, of course, we call high spirits and enthusiasm. But we don’t read about it in the newspaper or fret over the fragile mental state of those poor boys in Whereversville. After all, they are just guys.

So here comes the hurry to toss the witches of Colombia onto the same pyre as witches of old, the handy place for women who ask and weep and kvetch too much. Not only is this treatment unnecessarily harsh, but it overlooks a big fat fact: something is happening there and in Le Roy and various other towns (the oddest is the Tanganyika Laughter Epidemic of 1962 involving a hundred girls laughing uncontrollably for almost a year at a boarding school in Tanzania). How odd and entirely profound that behavior can spread like infection. Isn’t this at least interesting and worthy of consideration? But the psychiatrists’ Bible, the DSM-5, doesn’t have a code for it—people only, not groups, for the shrinks. But as Nietzsche once wrote, “In individuals, insanity is rare; but in groups, parties, nations, and epochs, it is the rule.”

Some might argue that close study is stymied by sensitive feelings and the need to respect, sort of, the groups studied. After all, men—particularly doctors—aren’t the nicest people, and cranking out potentially uncomfortable articles certainly is not the way to win friends and gain grant funding. So, the conventional wisdom goes, the medical community, out of kindness, is allowing the psycho-socio-politico- anthropologic phenomenon to rattle on, mostly shrugged off.

A likelier explanation though is this: that the collusive decision to regard as simple nuttiness a well-defined and predictable condition affecting a large swath of vulnerable people is a type of contagious group-think. In other words, it’s a mass psychogenic illness.