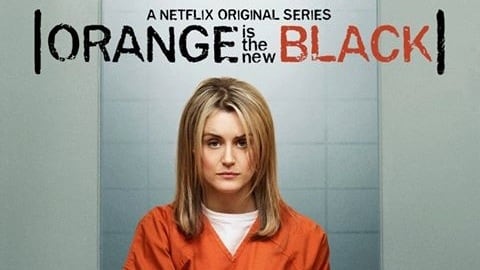

In case you’ve been living under a rock somewhere and still haven’t heard, “Orange is the New Black” has taken TV audiences by a storm since its release on Netflix last week. The wildly popular, sexy, and addictive show—I may or may not have binge-watched the entire first season over the course of a single sleepless weekend—follows Piper Chapman as she serves a 15-month sentence in a federal women’s prison.

The charm of the show lies in its writers’ uncanny ability to subvert stereotypes at every turn. Each character is wonderfully nuanced, and nobody is who they seem to be. Piper, a New York WASP who loves juice cleanses, artisanal soaps, and her fiancé Larry Bloom, seems as straight and straight-edged as can be—until you learn about her felonious ex-girlfriend Alex. Alex, whose work in an international drug cartel has landed her in the same prison, gets mistaken for a “privileged rich girl,” but we soon find out that she was once a painfully poor and bullied kid. Suzanne, whose loopy behavior has earned her the nickname “Crazy Eyes,” turns out to be an uncommonly smart woman who can recite from obscure Shakespeare plays at will. And then there’s Sophia, a transgender woman of color actually played by a transgender woman of color; she takes the cake for the most captivating, nuanced, multidimensional character of all.

Because the writers behind “Orange” are so amazingly good at creating complex, stereotype-busting characters, it comes as a shock when we meet Larry, his mother, and his father—the show’s Jewish characters, all of whom feel cut from cardboard. (Series creator Jenji Kohan is herself Jewish.) The more you watch them, the more you start to feel like these three people are really just sad caricatures of themselves. And the more you start to wonder: why, after doing such a brilliant job on every other aspect of the show, have the writers suddenly resorted to stock characters and tired TV tropes?

Take Larry. A struggling writer and Nice Jewish Boy, he’s got that tortured, brooding, nebbish quality we’ve come to associate with Woody Allen—despite the fact that he’s young and conventionally good-looking. He jokingly attributes his dark view of the world to the fact that he’s a Jew. His helicopter mom, who’s forever butting into her son’s personal life and nagging her husband to eat another bowl of soup, fits the Jewish mother stereotype to a tee. As for Larry’s dad, he is (what else?) a lawyer. And not just any kind of lawyer, but the kind who’s not afraid to use his legal and monetary capital to put pressure on higher-ups. It’s a quality that comes in handy for Larry on more than one occasion.

When Piper is sent “down the hill” for a punishing bout of solitary confinement, Larry freaks out, then quickly starts placing calls. Speaking to prison personnel, he says, “My father is a lawyer. I know her rights.” When that doesn’t work, he mentions that he’s left a message for the governor’s office and threatens, “If I don’t get a call back from somebody, soon, you people are going to have a f***ing lawsuit on your hands.” His interlocutor hangs up on him, but Larry’s tactic actually works. In a later scene, we watch as Piper’s prison counselor gets dressed down by his superior, who orders him to take the woman out of solitary, pronto. Why? Because:

Her fiancé is raising a stink bigger than the s*** I took this morning. Christ, he’s probably got the Obamas on the phone by now! These liberal, wealthy offenders—they’re connected. And if they review this, the paper trail is going to be sweaty. So do us all a favor, and get her out of there.

You’ll notice that the actors in the scene never once utter the word “Jew.” They don’t need to. The implication here is veiled but obvious. Piper, the liberal, wealthy offender, is connected to Larry, a liberal, wealthy Jew. And he has connections on Capitol Hill; in fact, the prison personnel allow themselves to speculate (albeit hyperbolically) that he’s got a direct line to Obama himself.

What emerges from this scene, then, is a continuation of the stereotype of the modern American Jew, who is understood as a powerful and intimidating bully. He’s someone you don’t want to cross. He’s got the president’s ear, and he’s not afraid to speak loudly.

It doesn’t take a deep familiarity with the news to see where the “Orange” writers might have gotten this idea. Those who followed the Chuck Hagel witch-hunt last winter will hear in the above-mentioned scene echoes of the now-Defense Secretary’s confirmation battle. At that time, Hagel came under harsh and unrelenting criticism for his 2008 statement that “the Jewish lobby intimidates a lot of people up here [on the Hill],” in which some detected a whiff of the old anti-Semitic trope about Jewish control. Critics also raised concerns over what they saw as Hagel's insufficient support for Israel. In the end, Hagel was confirmed—but only after he repeatedly apologized for his 2008 statement, acknowledged that he should have made reference to the “Israel lobby” instead, and reaffirmed his commitment to the Jewish state in no uncertain terms.

This week saw Samantha Power, Obama’s pick for U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, walking back her previous statements on Israel in a similar way. Distancing herself from a 2002 interview in which she’d noted Israel’s “major human rights abuses,” she adopted a strikingly pro-Israel line, even going so far as to say “the United States has no greater friend in the world than the state of Israel.” As many noted, once she’d shown her willingness to play ball with the pro-Israel right, the groups that initially raised concerns about her nomination happily endorsed her.

That the release of “Orange” and the Power hearings happened to coincide is, of course, just coincidence; the scriptwriting obviously preceded this week’s hearings and may have preceded the Hagel hearings, too. But that doesn’t change what these examples show: the trope of Jewish intimidation—which verges unnervingly close to the dangerous, anti-Semitic notion that Jews control everything—is ascendant in American discourse. Because it's exaggerated in today's media, it makes sense that American TV shows—even the brilliant ones, even the ones whose writers aren’t lazy—are picking up on and reflecting that trope. This is as true of "House of Cards" and "Saturday Night Live" as it is of "Orange."

As a viewer, I found the portrayal of Jewish characters in “Orange” somewhat disappointing. As a political observer, though, I can’t say I’m at all surprised.