At the 47th Division for Planetary Sciences (DPS) meeting in Washington, DC, researchers with the New Horizons mission presented the latest findings from the July flyby of Pluto.

The main theme: We know so much more than we once did, but we are a long way from understanding exactly what makes Pluto tick.

The first surprise? Something that shouldn’t be there at all.

Maybe, researchers posited, Pluto has volcanoes of ice.

It’s one possible explanation for what was possibly the biggest surprise from July: the discovery that Pluto is still an active world. Earth has a thick atmosphere with lots of weather, a hot interior, and oceans. Pluto has none of those things.

But processes under the surface seem to keep things just warm enough inside to pump material up, in the form of volcanoes—not of magma, but of nitrogen, methane, and other volatile materials.

We see ice volcanoes on other worlds, but those are moons orbiting giant planets, where their interiors are churned up by the strong gravity and other processes. What is keeping Pluto warm enough to erupt is something we don’t yet understand.

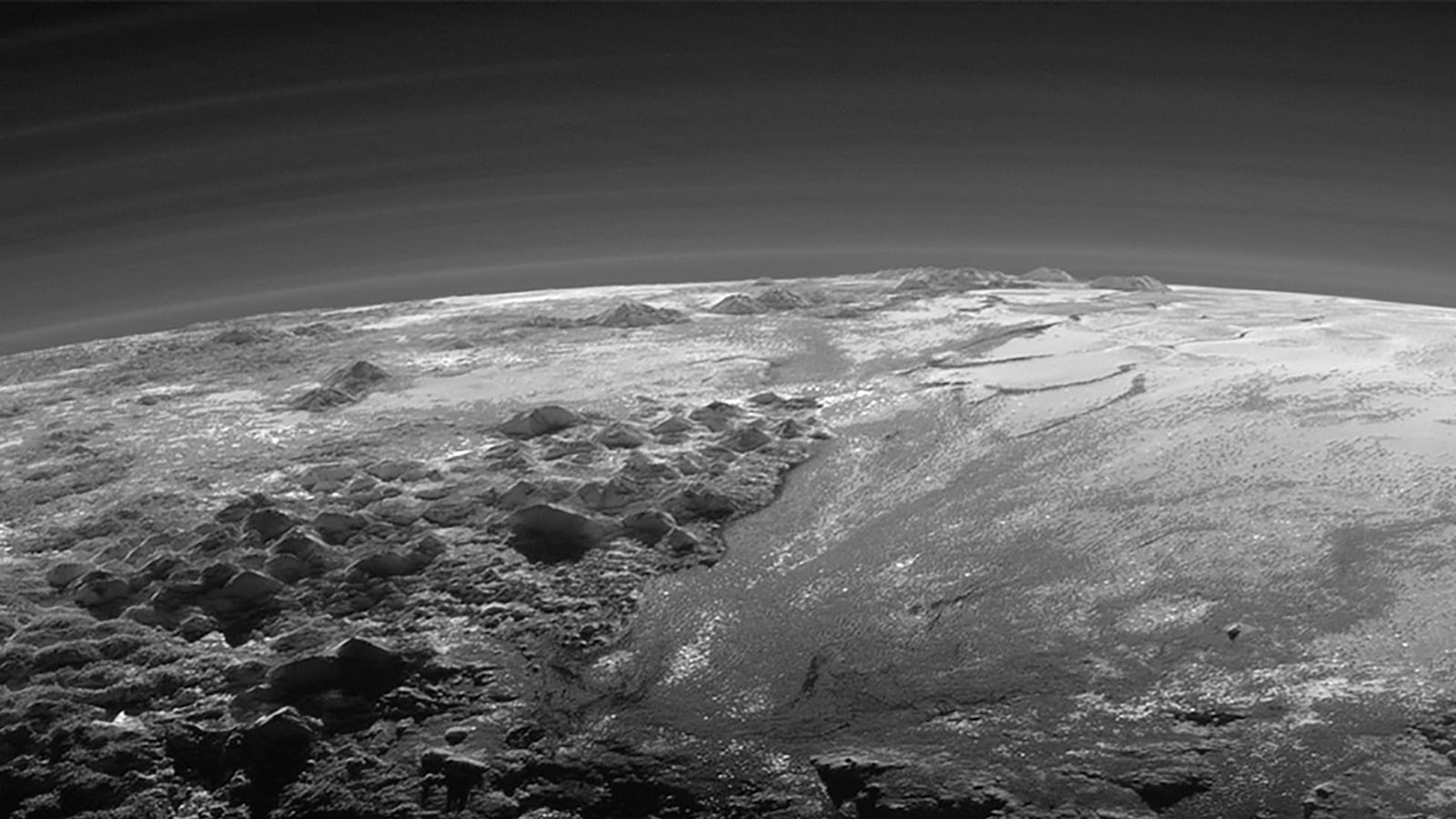

Jeff Moore of NASA’s Ames Research Center showed pictures of mountains lined with deep craters at their centers. This suggests—if not proves—volcanoes. These objects are at least 5 kilometers high, and look strikingly like the volcanoes on Mars.

Oliver White of SETI joked that ice volcanoes are the “least weird” hypothesis to explain much of what we see.

But volcanoes aren’t the only surprising things going on. If you look at Pluto’s surface, the most striking feature is the heart-shaped region known informally as Tombaugh Regio. (All the names New Horizons researchers use are provisional, since they haven’t been formally approved by the International Astronomical Union.)

The heart is free of any craters and has many smooth places bounded by deep trenches. Like your ex, the heart is made of ice, but made of nitrogen and methane rather than water.

Most craters were formed by meteorite and comet impacts in the early Solar System. To get rid of craters, something has to wipe them out. On Earth and Mars, that’s weather. Worlds without weather, such as the Moon, have many more craters. Some of the Moon’s craters were erased by volcanic flows.

Pluto’s surface may be shaped by other processes below, based on how Tombaugh Regio looks.

Jeff Moore argued that the smooth regions (which he called “topographic blisters”) are akin to bubbles of gas produced by convection in a boiling pot. However, the bubbles are flows of nearly-melted ice made of nitrogen, methane, and other chemicals that are gases under ordinary conditions on Earth.

Another surprise was the mountains. Icy moons orbiting the giant planets are very smooth, but Pluto has mountains as big as those we find on rocky worlds like Earth or Mars.

The current thinking is that these mountains are made of water ice frozen into shapes hard as any rock. These mountains may be literally floating on top of the flowing, nearly-melted ices below the surface, like how the continents float on top of the mantle on Earth.

The result is something like plate tectonics, where all the pieces are ice rather than rock. Pluto has many fissures that show material has forced its way out, spreading surface landmarks like craters apart.

But what is keeping the interior warm? We don’t know. Yet.

The air up there

Pluto also has an atmosphere, though one that is much thinner and colder than ours. Like Earth, much of it is nitrogen, but the resemblance ends there. The much weaker gravity means the atmosphere is spread out, but researchers were surprised to find it’s less spread out than they thought. The result is that less gas is escaping into space than scientists expected.

The big surprise: Pluto has lost much less of its atmosphere than predicted.

Another very exciting discovery was the presence of haze, which on Earth is largely produced by water vapor or air pollution. On Pluto, haze is made by ultraviolet light striking nitrogen and other molecules in the atmosphere, creating organic compounds known as tholins. These molecules fall to the surface and create the beautiful colors we see on Pluto, as described by Leslie Young of the Southwest Research Institute.

Haze makes light shining through the atmosphere look blue—another surprise—and diffuse the light falling on the surface. Alan Stern, the lead investigator on New Horizons, pointed out that the haze glows enough to let us see a little bit of the night-time surface, which ordinarily would be hidden from view.

Charon is caring

Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, make a double system: they both orbit a spot in empty space between them, and their gravity makes them always face each other. However, Charon looks strikingly different than Pluto, and is in its own way as weird and wonderful as the dwarf planet itself.

Charon is two-faced. The northern hemisphere is rough and jumbled, with a huge region informally known as Mordor Macula, colored by tholins. The southern hemisphere is much smoother, with a fissure dividing north from south. The current hypothesis is that Charon and Pluto were both born out of a body that was shattered by an impact early in history, which is also how the Moon was created.

But Charon has no atmosphere. Not a minimal atmosphere—none of the measurements have detected any atmosphere, which was another surprise.

Charon also is far less colorful than Pluto, and shows no sign of internal activity. No ice volcanoes, or anything like Tombaugh Regio.

Potato-shaped moons

Charon and other large moons of the Solar System steal the spotlight, but there are a lot more small potato-shaped moons. Pluto has four: Nix, Hydra, Styx, and Kerberos. These moons make a miniature Solar System around Pluto and Charon.

“It’s not chaos. It’s pandemonium,” says Mark Showalter of the SETI Institute.

These moons don’t behave the way we expect: they don’t present the same face to Pluto, like Charon does. Instead, they tumble as they orbit, with Hydra in particular spinning more than 80 revolutions each time it completes an orbit.

In fact, the researchers who spoke at DPS think all the strangeness could be linked. Perhaps the big impact years ago that created Charon also made the other moons, along with at least one other moon that got kicked out of the system. A secondary impact would also spin Hydra up to its current fast rate.

New Horizons flew by Pluto in July, but to save weight and cost, the antenna to transmit data back to Earth is small. As a result, only about 20 percent of the data the probe took has arrived at Earth.

Over the next year, we’ll get the rest of that—including far more detailed images and chemical analyses. Maybe some of those new data will help solve the mysteries of this tiny, beautiful world.