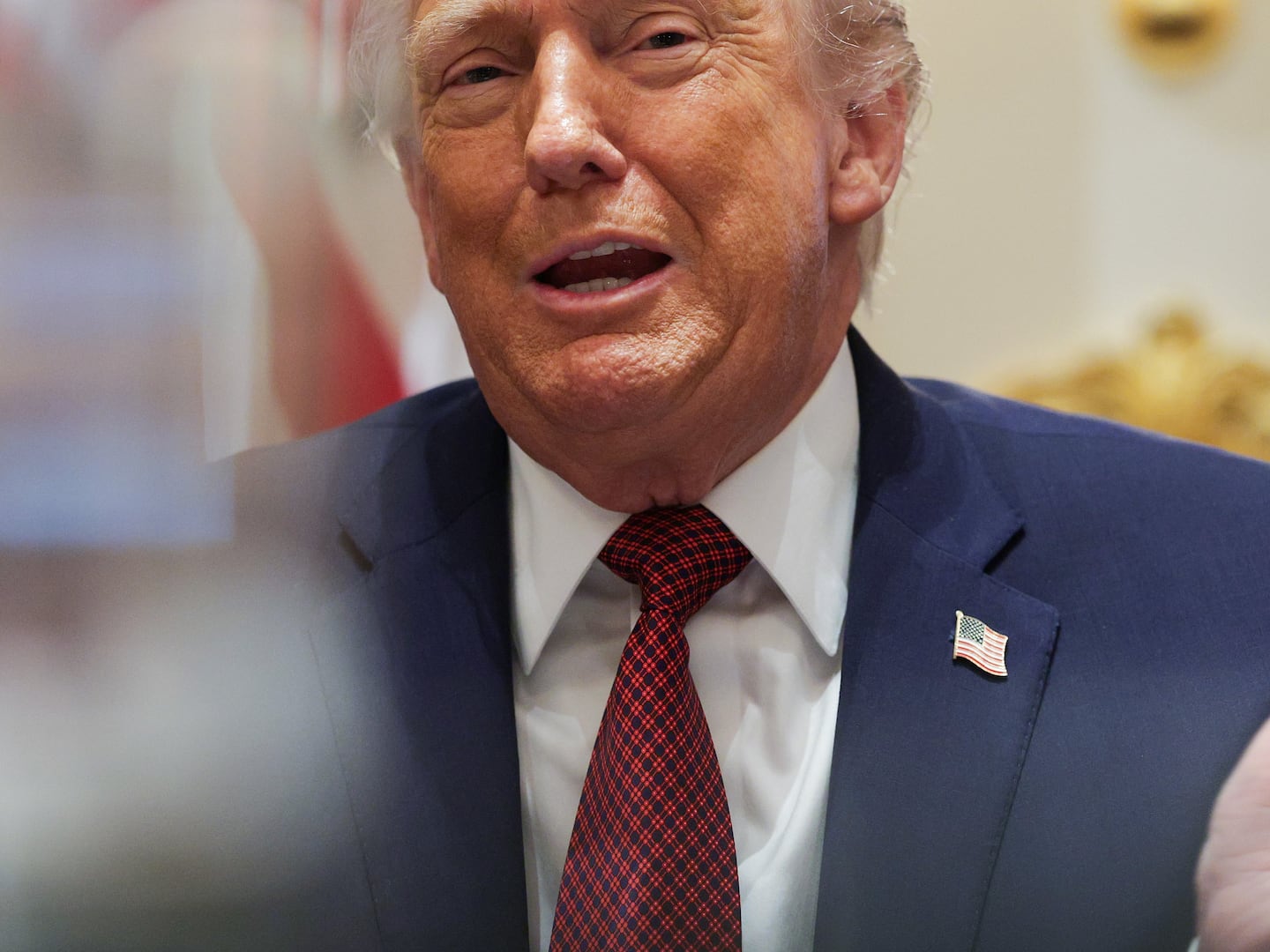

Justice Department Special Counsel Jack Smith argued in court papers on Thursday that the nation’s expansive presidential powers don’t permit Donald Trump to whisk hundreds of classified records away from the White House—and they certainly don’t justify him lying to the feds to cover it up.

The special prosecutor investigating the former president over his hoarding of classified documents at Mar-a-Lago finally responded to Trump’s attempts to get his criminal case dismissed, tearing apart arguments that he said would put the billionaire above the law.

“Trump’s claims rest on three fundamental errors, all of which reflect his view that, as a former president, the nation’s laws and principles of accountability that govern every other citizen do not apply to him,” Smith wrote, adding that Trump is now seeking to justify the way he would “lie to the government, conceal records, and obstruct the grand jury’s investigation.”

The much-anticipated court filing lays out a broader version of the DOJ’s investigation, which is currently before a Trump-friendly federal judge that the former president appointed shortly before leaving office. The DOJ court filing spends considerable attention focusing on the way Trump tried to cover up the crime of stealing so many classified documents, with prosecutors justifying their initial criminal inquiry but also putting significantly more weight on the consequences of having Trump try to stymie that very investigation.

Smith’s team had until Thursday to respond to Trump’s four separate motions to dismiss, laid out across 75 pages of court filings in February, which largely seek to justify the way he hoarded classified records at his South Florida oceanside estate.

In one, Trump’s lawyers told the judge that Trump, as commander-in-chief, had the discretion to deem the mounds of classified government records as “personal”—despite the National Archives and Records Administration’s attempts to collect them for their historical value.

Trump’s team is also trying to knock away the DOJ’s ability to levy criminal charges in this case, pointing to how the case got started. The DOJ only started investigating Trump after getting a referral from National Archives bureaucrats who were frustrated at the former president’s refusal to turn them over after leaving the White House. Trump’s lawyers claimed that the Presidential Records Act only allows the National Archives to pursue a civil case as the “exclusive remedy for records collection efforts” and “forecloses criminal investigations.”

In another court filing, Trump’s defense team claims that that he should be considered completely immune to criminal charges on the notion that he was still U.S. president when he allegedly decided to designate stacks of sensitive government paperwork as a “personal” archive—that is, long before they were found scattered around his mansion by FBI agents.

This presidential immunity argument echoes the constitutional question now being considered by the Supreme Court, which will hear arguments next month and ultimately decide if Smith can put Trump on criminal trial in Washington for trying to rig the 2020 election.

On Thursday, Smith also attacked Trump’s attempts to equivocate his Mar-a-Lago scandal to the way President Ronald Reagan kept his personal diary—which was full of classified information—after leaving the White House in 1989. In court papers, Trump’s lawyers have pointed out that the DOJ previously allowed Reagan to do it and essentially made the argument: Reagan did it, why can’t Trump?

“DOJ and NARA have adopted this position with respect to government officials whose last name is not Trump,” defense lawyers Todd Blanche and Christopher Kise wrote in February.

But federal prosecutors countered that argument with force, contending that Trump can’t simply grab stacks of sensitive government paperwork and suddenly call it his diary.

“This case involves classified records created by intelligence and military officials for highly sensitive presidential briefings. Trump did not create them, they do not reflect his personal thoughts, they came into his possession only through his official duties, and (except for one charged document) bear classification markings,” the feds wrote. “They have no resemblance to diaries.”

This federal case in South Florida is only the latest example of Trump trying to dodge legal consequences by claiming sweeping and unchecked powers. At his recent bank fraud trial in New York City, which ended with a $464 million dollar judgment against him, Trump tried to assert an unrestrained ability to give his real estate portfolio whatever value he could dream up.

In Washington, where Trump is expected to face criminal trials for engaging in an aggressive plan to remain in power after losing a national election, his lawyers have insisted that presidents could dodge all kinds of criminal charges—even if they ordered military commandos to kill political rivals.

On Thursday, Smith’s prosecutors called out Trump’s latest theories of unhampered authority, which would give any president king-like abilities to declare any government document his own personal property—and keep any decision “categorically off limits” by any judge, anywhere. Smith attacked Trump’s distorted version of reality.

“On Trump’s contrary reading, a departing president could unilaterally convert classified

government records—containing the nation’s most closely guarded military, diplomatic, and national security secrets—into his private possessions, leaving the government with no judicial recourse to recover its own property and protect the nation from the risk that the former president may disclose these secrets to a foreign adversary, post them on the internet, or sell them to the highest bidder,” Smith wrote.

In one footnote, federal prosecutors gave Trump a curious opening—just not an escape hatch. They told Judge Aileen Cannon that Trump might legitimately argue that he actually did designate these records as “personal” and had no criminal intentions—known as mens rea—but that they haven’t even seen an inkling of proof yet.

“At trial, Trump may offer a defense that he did not act willfully,” they wrote, with DOJ lawyers adding that the argument “would, of course, require as-yet-unseen evidence to support it.”

Even that, they said, wouldn’t be enough to prove the obvious: The classified records were in his possession without permission.

Cannon is expected to review the arguments and decide whether she’ll keep the case as is, or knock down some of the criminal charges Trump currently faces. But her critics have noted an appalling track record so far, given her penchant for consistently ruling in Trump’s favor.

Cannon significantly delayed the case from the very start, freezing the FBI’s investigation and appointing an independent monitor in faraway Brooklyn, New York, until a federal appellate court stepped in and told her to back off. Since then, however, she has continued to slow down the court process and push back the trial, which at this point might not start until the summer.

Her more recent actions have only fueled further concerns. Just yesterday, the judge used choice words when deciding to formally accept amicus briefs—legal input from third parties—from conservative lawyers who claimed that “Jack Smith does not have authority to prosecute this case” because “he wields tremendous power, answerable to no one.”

In response, Cannon on Wednesday admitted their legal briefings and noted that they “bring to the court's attention relevant matter that may be of considerable help to the court in resolving the cited pretrial motions.”