By the time a country finds out it’s being led by somebody with a serious personality disorder it’s usually too late. Unlike the contentious science of clinical psychology, history does at least deliver objective proof of one thing: a leader unprepared for office by reason of strange behavior can wreck the world.

The first modern example of what could follow if an unhinged mind gained control of a country and its military appeared astride a cavalry horse, wearing a white cloak and a polished, spike-topped helmet as he reviewed his army’s officer corps in 1888.

Kaiser Wilhelm II came to the throne at the age of 29. He was born into the inbred web of European royalty with relatives whose realms included Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Great Britain. In fact, Europe was run a bit like a family business where none of the brothers, nephews, and cousins had much contact with reality and used their countries as vehicles for their personal egos.

Of them all, Kaiser Bill was the most lethally dysfunctional. Any clinical diagnosis of him begins with a physical impairment. His left arm was permanently damaged at birth. That alone wouldn’t explain his future behavior. Sigmund Freud, no less, declared that the crippled arm itself wasn’t to blame but his mother’s response. “She deprived the child of her love” said Freud, “and when the child was a mighty man he had to prove by his actions that he never forgave her.”

This was a man whose greatest possession was his army—an army built on the legendary disciplines of Prussia. His first proclamation as kaiser announced, “We belong to each other, I and the Army; we were born for each other.” He explained just what that might mean to a bunch of recruits: “If your Emperor commands you to do so you must fire on your father and mother.” (He may have had his own mother in mind as he spoke.)

To the German people he said, “There is only one master in the Reich and that is I; I shall tolerate no other.” He referred to members of parliament, the Reichstag, as “sheepsheads.”

In an impulsive, headlong surge of personal egomania Kaiser Bill was, more than anyone else, responsible for the World War that broke out on Aug. 4, 1914—a war whose causes beggared all reason and that cost nine million military deaths, decimating a whole generation of Europe’s male population, and seven million civilian deaths.

Recently, psychologists who have put Kaiser Bill on their couch have decided that he was a prime case of what they call histrionic personality disorder—someone who acts in a very emotional and dramatic way, drawing attention to themselves, needing reassurance and approval. There’s a simpler way to put it in military terms—mine is bigger than yours. The kaiser wanted and got the biggest army and the biggest navy.

As calamitous as it was, the “war to end all wars” was just the first act in a succession of disasters directed by men who came to power with severe personality disorders: in Russia Joseph Stalin, in Italy Benito Mussolini and—again in Germany—Adolf Hitler. All were monsters and all exhibited certain common traits: narcissism, intolerance of criticism, impulsive decision-making, unpredictability and disregard of professional advice—political or military.

Like the kaiser, Stalin’s demons were shaped in childhood, including the psychological effects of being born with a deformed arm, being scarred by smallpox and of being born into a dysfunctional family. He was never diagnosed during his lifetime but extracts from the diaries of his personal physician, published long after his death, portrayed all the characteristics of paranoia.

Stalin took any kind of criticism as a personal threat. The most murderous result was The Great Terror, the series of purges of the Communist Party carried out in the 1930s in which at least half a million people were executed and as many as 12 million sent to labor camps. Following that, as commander-in-chief in World War II Stalin made a series of blunders but showed no remorse for the high casualties caused. Successful generals had to be careful not to take personal credit, lest they were disappeared.

Of course, the ultimate monster was Hitler.

The abyss of Hitler’s mind is beyond rational understanding. The monstrous consequences of his life make the familiar diagnoses seem trite. As Ian Kershaw, one of his more recent biographers warned, dealing with Hitler’s symptoms risks “reducing the cause of Germany’s and Europe’s catastrophe to the arbitrary whim of a demonic personality.” Nonetheless, Kershaw does describe Hitler’s “boundless egomania” and adds “he owes no ties outside his own ego” and behaved like a prima donna “hypersensitive to criticism.”

In The Hitler of History, John Lukas’s astute dissection of more than 50 years of biographies, he settles on 1921 as a moment when Hitler’s inner poison was first outed in public, in a speech: “There is only defiance, hate, hate and again hate. To hate, to be hard, a lesson devoid of love.” Later, in 1926, when Goebbels first meets Hitler, Hitler tells him how he had learned to hate: “God has graced our struggle abundantly. God’s most beautiful gift is bestowed on us as the hate of our enemies, whom we in turn hate from the bottom of our hearts.”

However, on the threshold of the apocalypse, in 1938, Hitler underwent a wesensanderung—a significant shift in personality. His concern with his health became acute. Throughout his life he had minor ailments but now he feared that bad health would deny him the chance to create the greatest of the Reichs. He stopped taking physical exercise (in earlier life he had hiked the hills of Bavaria in lederhosen even in winter) changed his eating and drinking habits and withdrew from social life. He believed he was ill and had little time left. Albert Speer, his fawning architectural accomplice, was ordered to build the new Reich chancellery in Berlin within a year—Speer recorded in his diary: “He feared seriously that he would not live much longer.”

Dragged along in the shadow of Hitler was the prototypical strutting demagogue, arousing a whole nation to the spell of fascism, Benito Mussolini. In young adulthood Mussolini was prone to violence, including violent sex (he stabbed one of his lovers) and had the drive of an egomaniac. Like Hitler, Mussolini was intolerant of criticism, subject to sudden changes of mind and mood, announcing that he would rather be feared than loved. He frequently attacked with venom those who attempted to advise him.

One feature that all these monsters have in common is the relative ease with which they gained power. The kaiser’s Germany was a weak parliamentary democracy in which the monarch’s power remained absolute. Stalin came to power through revolution and hacked through flesh to the top. Mussolini sold a persuasive new ideology, fascism, as a system that promised to make a shambolic country great again. Hitler and his gang shrewdly exploited Germany’s economic collapse, swiftly subverted fragile national institutions and gained dominance over the military.

There was no possibility in any of these countries of disqualifying or removing a contender for leadership on the grounds of a clinical disorder, no matter how obvious or dangerous it became.

In recent U.S. history only one politician has been persuaded to leave a ticket for medical reasons—in 1972 Senator Thomas Eagleton was chosen as George McGovern’s Democratic running mate, but withdrew when it emerged that he had been hospitalized for depression and had electroshock treatment.

McGovern lost in a landslide to Richard Nixon, which is ironic since it was Nixon’s presidency that was ended by Watergate, a completely needless criminal enterprise that could be explained only by an acute clinical disorder, Nixon’s paranoia.

Later, Nixon was at least able to discuss his own mental state with striking candor.

In his cathartic television confessions to David Frost, Frost brought up the issue of paranoia and Nixon replied, “… is this whole business of, am I paranoiac about hating people and trying to do them in? And the answer is: at times, yes. I get angry at people. But in human terms, as far as I am concerned, I believe that an individual must never let hate ruin him.”

As the Nixon tapes have revealed, he was remarkably uncouth, petty and spiteful toward perceived enemies, as well revealing a toxic anti-Semitism. But the real tragedy (and puzzle) of Richard Nixon was that he combined base and vengeful instincts with a commanding political and geopolitical literacy.

In a column about Donald Trump, Frank Bruni wrote, “We throw around terms like demagogue and fascist, but I’m not sure he’s coherent, consistent or weighty enough for either.”

Recent history is burdened with the appalling human cost of fascists and demagogues and the salutary point is, or should be: we don’t get to know whether they are weighty or not until they get what they crave most: power.

Even today, any attempt to demonstrate that a clinical condition renders a contender unfit for public office is fraught with problems. For one thing, who, exactly, is qualified to make that judgment? However observable the symptoms may seem, a diagnosis that justifies a legitimate legal response won’t easily be forthcoming.

President Obama said this week, breaking with conventional restraints, “The Republican nominee is unfit to serve as president.”

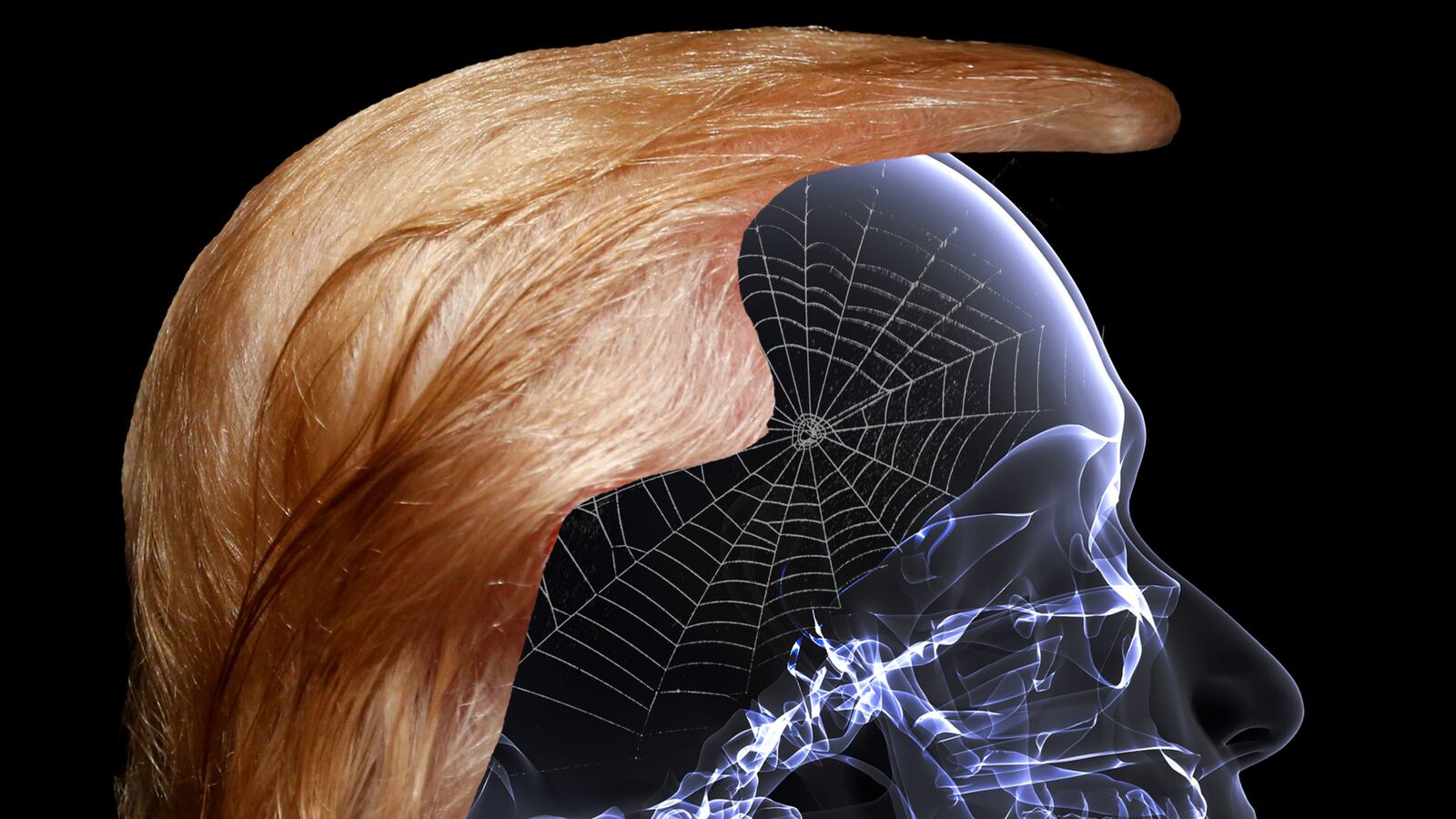

We are dancing around the issue, using euphemisms like unpredictable, inconsistent, irrational, thin-skinned and unprepared. For a while the Republican leadership really believed that once the primaries ended and the general election was underway Trump would experience his own wesensanderung, a personality change, though in this case one for the better, that he would suddenly be a decent, reformed character not given to twittering instant and mean reprisals. They don’t get it. Trump’s condition—his core character—isn’t susceptible to remission.

When Barry Goldwater ran for the Republicans in 1964 the pay-off on his TV ads was: “In your heart you know he’s right.”

A popular response to that was: “In your heart you know he’s nuts.”

If Trump really is nuts, what do we do about it, short of waiting for the moment to send the guys into the Oval Office with the strait-jacket?