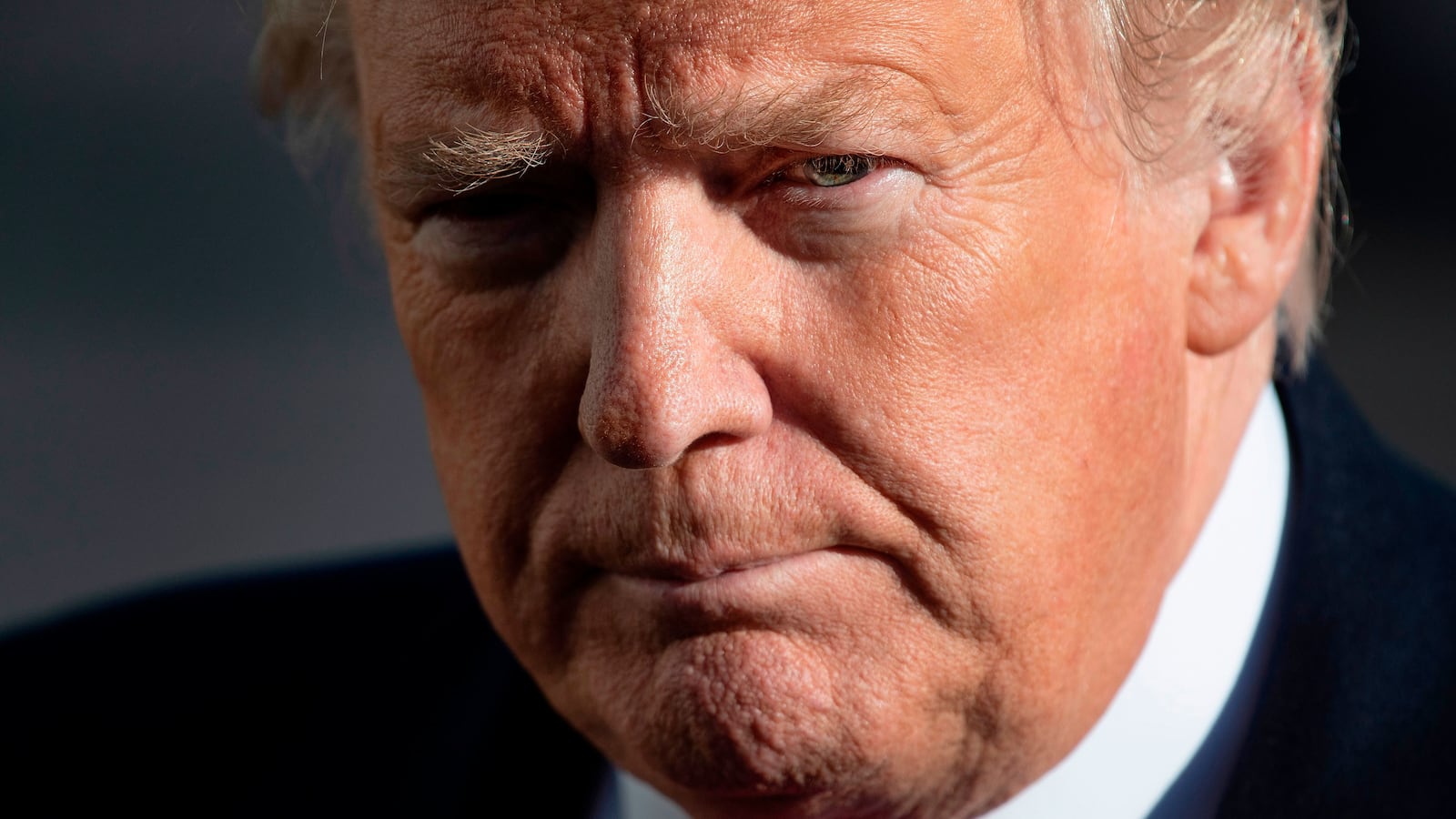

As Americans try to find familiarity in strange times, people have grasped at a sea of comparisons to try and fully capture Trump’s innate Trumpiness. Our most analogized president has been compared to Hitler and Stalin, Jesus, a chess grandmaster, and Julius Caesar. The Daily Beast’s Clive Irving likened Trump to an early-stage Mussolini. Frank Palmieri at AlterNet countered: Trump is no Mussolini, he’s Charles II of England.

But we’ve seen this before, over 2,000 years ago, when another insurgent faux-populist movement whipped disaffected citizens into an anti-establishment frenzy.

The echoes of his worldview can be heard nearly a century before Caesar’s rise, when Tiberius Gracchus convinced Roman citizens to hollow out their governing institutions. By the time Rome’s senators realized the full extent of their self-immolation, the Gracchi—and the Republic—were dead.

Tiberius Gracchus was born around 169 B.C., a richly privileged outsider in a time of declining public trust in a divided and weak Roman Senate. Early in his life, Tiberius recognized a Roman government lacking in resolve, bound by archaic norms and customs that pointlessly impeded real progress. He would change that.

One of Tiberius’ first notable public acts involved illegally negotiating and signing a peace treaty with the troublesome Numantines. Rome’s treaty agreements were deeply ritualized events normally overseen by Legates, the Republic’s senior officials. Tiberius’s boldness sparked a scandal not unlike that of a president installing his son-in-law in a sensitive diplomatic role over well-qualified career civil servants.

Tiberius’s stunning lack of respect for fundamental Roman values caused a shockwave among Roman elites. But Tiberius, far from the capital, had built support among rank-and-file soldiers and the working class. Plutarch, the dutiful Sean Hannity of his day, heaped praise on Tiberius first for launching and then for calling off a massive looting of Numantia.

What made Tiberius so dangerous was his determined incitement of the worst and most violent tendencies of his populist mob. On returning home from military service, Tiberius began swinging his institutional wrecking ball at Roman politics. As one of the first leaders of the populares, a “favoring the people” faction, Tiberius honed voters’ justifiable disconnection and anger into a lethal political blade.

Nothing was stable in Tiberius’ Rome. The Republic had been lurching from one military crisis to the next for nearly a century. Military life was long and brutal for Roman men, who often remained on military tour until the end of a conflict as long-running wars kept men away from their farms for years or decades, leaving fatherless families to scrape out difficult lives from the soil.

Rome’s Forever Wars forced many families to sell their farms to wealthy politicians while continuing to work them as tenant sharecroppers. Over time, this war-forged economy funneled ever-larger amounts of wealth and land into the pockets of Rome’s top 1 percent. The huge tracts of pristine farmland Rome captured during Tiberius’ time had those elites salivating over the prospect of new resources to control.

Tiberius made land redistribution his tentpole issue. As Tribune of the Plebs, he made an amorphous and overambitious pledge to redistribute newly-captured lands to soldiers and the poor. Tiberius’ Lex Sempronia Agraria proclamation was every bit as captivating among his supporters as Donald Trump’s chants of “Build the Wall” are today.

Tiberius Gracchus hid from the public a more kleptocratic reality: much of the “people’s land” would, in fact, be distributed to the Gracchi family and to his personal clients.

In 134 B.C., a fight broke out at one of Tiberius’s political rallies, and a mob dragged a fellow Tribune named Octavius from the stage after he stood in opposition to some of Tiberius’ more extreme proposals. Modern comparisons may not serve this moment well, because the bodily integrity of a Roman Tribune was held in the highest legal, religious, and cultural regard. You did not touch the Tribunes—it would be worse than punching the Queen of England.

Octavius’ public humiliation ignited a powder keg of resentment between the glacial Senate and a populace eager to “drain the swamps” and build their new Tiberius-promised homes on top of it.

The threat of removal from office proved too much for Tiberius to bear. In a desperate attempt to fend off his legal jeopardy, Tiberius made an unprecedented decision to seek an illegal successive term in office. It was an audacious power grab, even for a citizenry already accustomed to Tiberian legal excesses and excuses.

The Senate, surrounded, made an effort to throw Tiberius out. It was too little, too late. Years of free reign allowed Tiberius to crater public support in institutions like the criminal courts. Sapped from within by division, the Senate found itself unable to control even the execution of its own laws.

Finally free of rules Tiberius had rendered obsolete, the Senate assembled its own violent mob. Led by the Pontifex Maximus, the chief priest of Rome’s civic religion, senators attacked Tiberius in the Assembly. Some, lacking knives, swung clubs fashioned from the legs of shattered Senatorial benches. Only a few refused to participate in the murder.

After his death, Tiberius’ younger brother Gaius succeeded him as Tribune. The populares weren’t going away. The slow corrosion Tiberius set in motion continued to spread until the Republic’s final collapse, under Caesar at the Rubicon, almost a century later.

Tiberius demolished Romans’ high-minded belief in the sustaining power of political customs and traditions. In a few minutes of violent fury, the Senate had proven Tiberius right. Norms that had protected the Republic from strongman authoritarianism for centuries had shattered. Rebuilding them proved too costly.

American institutions may appear stronger than those of Republican Rome, but our unwillingness to use the Constitution to protect our country against Donald Trump’s new populares will set us on the same grim path. Speaker Pelosi’s decision to begin impeachment hearings is a reassuring step. Now the Senate must set aside partisanship and rise to this serious moment. The risk of long-term or permanent damage to our institutions grows daily.

It’s when strong governments refuse to protect themselves, when they bow to the siren song of false populism, that we fall short of our national values. Tiberius Gracchus and Donald Trump have beguiled us with two echoes of the same dangerous song. There’s still time to tune Trump out.