Hating Bill and Hillary Clinton has been a conservative cottage industry for a quarter-century. But ever since Bill’s self-inflicted sex scandals overtook dark talk about shadowy schemes in his second term, the most unhinged ideas about the Clintons faded into the fringe. Until now.

Donald Trump has grabbed hold of Clinton conspiracy theories with both of his tiny hands, shaking loose names like Vince Foster and introducing them to a new generation. There’s more where this garbage came from—festering heaps of paperbacks and VHS tapes that had been rotting in partisan landfills.

So let’s air the old accusations out and expose them to sunlight to show how ugly and absurd the work of the Clinton conspiracy entrepreneurs has been. In the second edition of my book Wingnuts, I added a new section on the unhinged Clinton haters and how they foreshadowed the era we’re living in now. Many of the names echo on in our politics today, from Roger Ailes to Citizens United to WorldNetDaily to an unexpected cameo by then-conservative Ariana Huffington. An edited excerpt is below.

***

Political thoroughbred Bill Clinton personified his generation’s ambition and indiscipline, traits that turned him into a culture-war lightning rod. Bubba’s political baggage included more than just his periodic “bimbo eruptions”—there were also unsettled debates about the late ’60s and feminism, with Hillary Clinton cast as the villain.

During the 1992 campaign, Republican operative Floyd Brown—author of the infamous race-baiting Willie Horton ad four years before—pursued a new partisan venture named Citizens United, scrambling to finish a book with a young deputy investigator named David Bossie called Slick Willie: Why America Cannot Trust Bill Clinton, which accused the candidate, in liberal journalists Joe Conason and Gene Lyons’ words, of “dodging the draft, raising taxes, coddling blacks, chasing women, corrupting state agencies, flip-flopping on abortion, awarding special privileges to gays, promoting secularism (and witchcraft!), wrecking the school system, flirting with socialism, and, in its stirring final chapter, blaspheming the Lord with his campaign slogan of a ‘New Covenant’ between citizens and government.”

Hillary was considered fair game as well. The New York Times counted at least 20 articles in major publications during the presidential election that compared Hillary Clinton to Lady Macbeth. At the 1992 Republican convention, she was derided as a “radical feminist” and in a pointed pushback, Marilyn Quayle, the wife of the vice president, said: “Most women do not wish to liberated from their essential natures as women.” A cover story in U.S. News and World Report summed up the situation with this opening paragraph: “For some, she’s an inspiring mother-attorney. Others see in her the overbearing yuppie wife from hell—a sentiment that led GOP media guru Roger Ailes to quip that ‘Hillary Clinton in an apron is like Michael Dukakis in a tank.’”

The 1992 campaign tracked along cultural more than policy lines—sex, drugs, rock ’n’ roll and post-collegiate trips to the USSR—and the weekend before the election, the anti-abortion group Operation Rescue took out full-page ads in USA Today and 157 other newspapers, posing this prominent question: “The Bible warns us not to follow another man in his sin nor help him to promote sin—lest God chasten us. How then can we vote for Bill Clinton?”

Clinton’s centrist strategy won the day with 370 electoral votes—but only 43 percent of the popular vote in a three-way race. For reasons that were moral, political, and now statistical, Clinton would be seen as an illegitimate president by his frustrated opponents.

In Congress, Republicans embraced a strategy of total obstruction, with GOP leader Newt Gingrich calling the Clintons “Stalinist,” “the enemy of normal people” and “counter-culture elitists.” Right-wing talk radio, just then coming into its own as a nakedly partisan cultural force, thrived with a polarizing target in the White House.

Soon after Clinton’s inauguration, a loose affiliation of old Arkansas enemies, conservative journalists, activist catalysts, leaders of the religious right, and big-money donors began their effort to demonize the new president.

When Deputy White House Counsel Vincent Foster killed himself in June 1993, he left a note agonizing over the negative public attention he had come under as one of the Clinton’s closest Arkansas associates from the Rose law firm. “WSJ editors lie without consequence,” he wrote, referring to The Wall Street Journal Op-Ed pages. “I was not meant for the job or the spotlight of public life in Washington. Here ruining people is considered sport.”

It was a tragedy, but the Clinton Haters smelled a conspiracy. Rush Limbaugh started to spout rumors that “Vince Foster was murdered in an apartment owned by Hillary Clinton,” rather than Fort Marcy Park, where his body in fact was found with gun in hand.

In Pittsburgh, the conservative owner of the Tribune Review, Richard Mellon Scaife, ordered reporter Christopher Ruddy (now the publisher of Newsmax) to investigate the conspiracy claims in an extended series of articles. Scaife was also the multimillion-dollar funder of what became known as “The Arkansas Project” within The American Spectator, in which a then-conservative journalist named David Brock broke the news of Clinton’s Little Rock dalliances and surfaced the first name of Paula Jones.

Scaife likewise funded the conservative nonprofit Western Journalism Center, founded by Joseph Farah, the former publisher of Scaife’s shuttered Sacramento Union (and now best known as the publisher of the for-profit conspiracy website World Net Daily). In a money-go-round, the Western Journalism Center paid for Ruddy’s series on Foster to be reprinted in other papers and publicized a pamphlet collecting it in full-page ads, raising half a million dollars from donors. Among the right-wing luminaries on the WJC board were Arianna Huffington and conservative professor Marvin Olasky, both of whom also worked as senior fellows at Newt Gingrich-associated Progress and Freedom Foundation. Scaife’s generosity came at a cost—when the American Spectator ran a critical review of Ruddy’s book, their funding stream was cut off. But in the meantime, the money train was rolling for the obsessively anti-Clinton crowd.

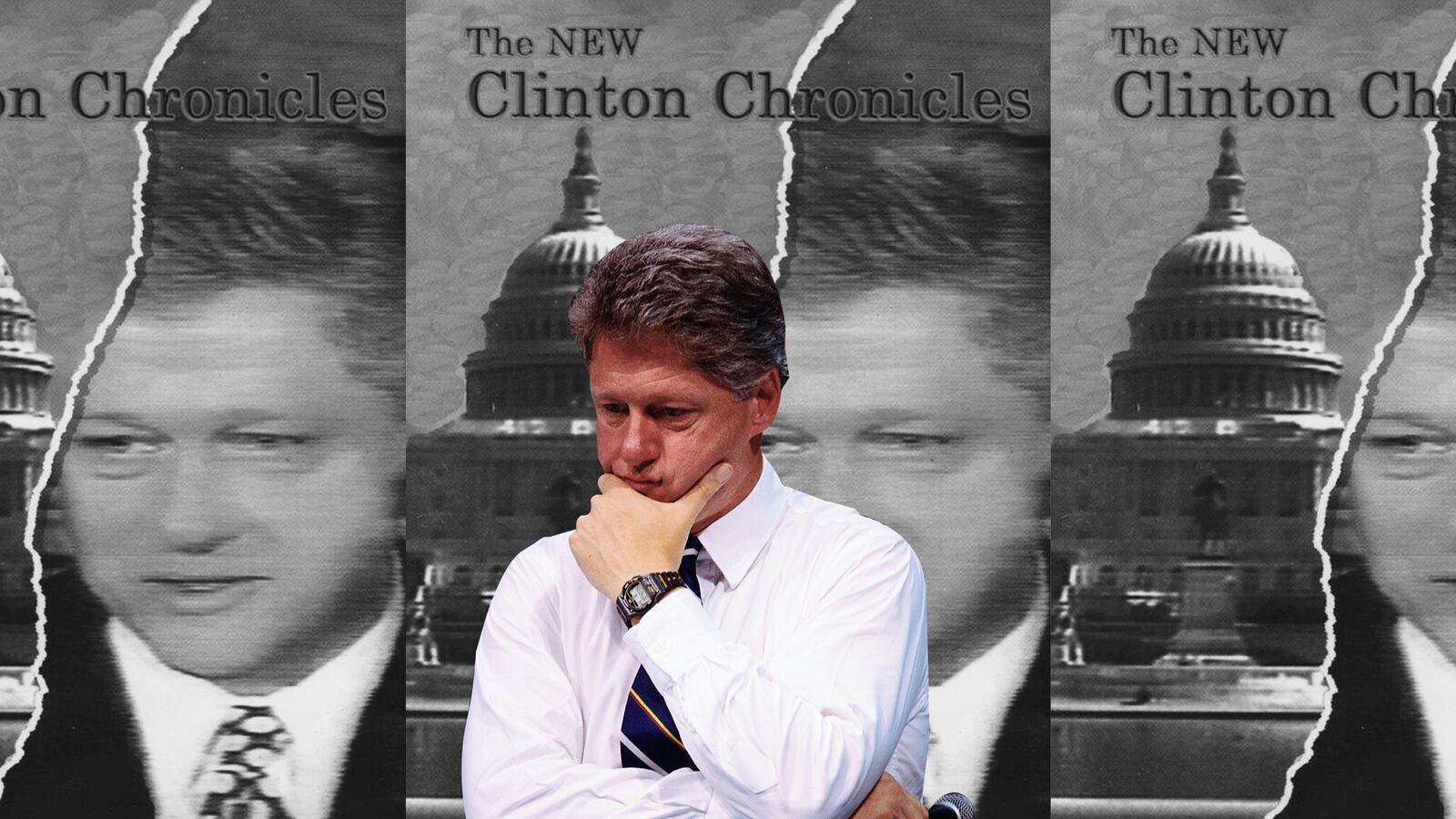

A flurry of further allegations followed, pushed out in those pre-Internet days by magazines, talk radio, and videotape. Tiny Jeremiah Films had previously produced videos for the evangelical circuit with titles like “The Evolution Conspiracy” and “Gay Rights, Special Rights.” Now a group with the lofty name Citizens for Honest Government was looking for anti-Clinton videos and Jeremiah Films’ Pat Matrisciana worked with veteran Arkansas Clinton antagonist Larry Nichols to produce a series.

Their first video, Circle of Power, was distributed by the Rev. Jerry Falwell’s Liberty Alliance. It began with Vince Foster’s death and went on from there to include 34 people who were allegedly killed at Bill Clinton’s behest. Former U.S. Rep. William Dannemeyer sent a list of the body count and demanded a congressional investigation.

Their followup, The Clinton Chronicles, cast an even wider net. Opening with the allegation that Clinton “achieved absolute control over the political, legal, and financial systems of Arkansas—as president he would attempt to do the same with the nation” the hour-long video expanded to include allegations of Clinton overseeing millions of dollars of cocaine smuggling from the tiny Mena airport and then laundering the money through foreign banks.

There were voiceover testimonies from Arkansas associates who claimed that the twentysomething Bill Clinton “went to Moscow and did business with them against the United States government.” “His sexual partners numbered over 100” the video’s narrator intoned, going on to allege that one talkative paramour was confronted by Clinton’s goons, who told her she could have “a federal job—or break her legs—whichever one was best.”

The video ended with a list of witnesses’ mysterious deaths and harassment, including Larry Nichols, who said he’d narrowly survived three attempts on his life. “Clinton can be a very dangerous individual,” the video explained.

Viewers of Jerry Falwell’s Old Time Gospel Hour were repeatedly treated to excerpts of the videos in the spring of 1994 and a half-hour infomercial offering them for purchase at the low, low price of $40 plus $3 for shipping and handling. It was a classic success story for conspiracy entrepreneurs. Citizens for Honest Government claimed sales of more than 150,000 videotapes and copies were sent to every member of Congress.

The accusations worked in the short term. The conservative base was fired up and they took control of Congress in the narrow-but-intense turnout of the 1994 midterm elections. But our modern pattern was established when Clinton roared back to re-election in 1996. Much of the promise of Clinton’s second term was squandered amid the impeachment crisis that followed the Starr Report and the unveiling of the Monica Lewinsky sex scandal. The president who once wisely remarked, “I have less and less control over my reputation but I still have full control over my character” made himself vulnerable to his enemies.

But the intensity of the Clinton animus on the right ended up spurring a backlash that helped propel Hillary Clinton to the U.S. Senate in 2000 and let Bill Clinton leave the Oval Office with a 60 percent approval rating. And so it goes.

The Clintons eventually won over some of their enemies—most notably Brock, Ruddy, and Scaife. Rush Limbaugh and Roger Ailes of course still linger and Citizens United became the plaintiffs in the infamous Supreme Court case that institutionalized big money.

But onetime defender Donald Trump careened to the other side of the spectrum, embracing Obama birther conspiracy theories and seeing an opening to demagogue his way to the 2016 nomination.

The scorched-earth strategy pioneered by partisan media against the Clintons has become the norm—and many of the attacks we’ll hear during the coming Big Ugly of an election have their roots in the first round of the Clinton culture wars.