The morning after Donald Trump was elected president, I woke up with one clear and horrifying thought: the ghost of Roy Cohn was moving into the White House.

Cohn, who had been Trump’s lawyer and friend, had also played a major role in securing the execution of my grandparents, the so-called “atom spies” Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. He made his name at the ripe old age of 23 as the assistant prosecutor in their trial. When I was very young, he floated ominously through my consciousness along with Judge Irving Kaufman, David Greenglass, and J. Edgar Hoover. They were the bad guys, the very mention of whom would prompt an angry hissing from various aunts and uncles like so many tires running out of air.

As Tony Kushner wrote in Angels in America, Cohn was “the polestar of evil.” He knew there was no evidence against my grandmother yet he helped manufacture the case against her. When Judge Kaufman wavered, Cohn pushed for her execution.

Cohn was a fascinating, if loathsome, figure whose short life was packed with contradictions. He helped create McCarthyism, represented the biggest mob bosses in New York City, hung out with Andy Warhol at Studio 54, foresaw and supported the Reagan revolution, fought against gay rights, and died of AIDS.

I was a college student in 1988 when I learned Cohn was gay and in the closet. While visiting the AIDS Quilt, the powerful public-art project displayed on the Smithsonian Mall, the very first panel my father and I stumbled upon was dedicated to Cohn. We couldn’t believe that out of over 49,000 panels his was the first one we’d see. It read “Bully Coward Victim,” and my curiosity was piqued. I would later learn that Cohn, with President Ronald Reagan’s help, gained access to the first clinical trials of AZT, a treatment for HIV/AIDS. Meanwhile the Reagan White House famously ignored and delayed responding to the growing crisis as the deadly virus spread across the U.S.

In 2004, I explored our painful family history in my documentary film Heir to An Execution, and though in recent years Cohn’s story tempted me to dig deeper, I had little interest in revisiting ours. Hadn’t we, the descendants of the Rosenbergs, said all we needed to say? The election of Donald Trump told me we had not.

Since becoming president, Trump has invoked Cohn numerous times. In frustration with then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions he lamented, “Where’s my Roy Cohn?!” and numerous commentators and journalists made the connections between Trump and Cohn abundantly clear. It’s been pointed out how Trump’s habits of lying, deflecting, blaming others, and not paying taxes are so very Cohn-like, and that’s all true. But we now know that Cohn did much more than shape Trump’s character—he singlehandedly introduced Trump to Washington and the national political scene. This boy from Queens saw a glittering world of power and wanted in. Cohn paved the way.

Cohn played Henry Higgins to Trump’s Eliza Doolittle, arranging an interview in 1984 with Washington Post journalist Lois Romano during which Trump announced he should be the nuclear arms negotiator for the United States. If there were signs that Trump could capably serve in this important role during the height of the Cold War, only Cohn must’ve seen them. Or, more likely, he saw another way to leverage his own influence, and Trump’s abilities or lack thereof had little to do with it. Trump had been busy building his fortune in NYC real estate and hanging out at nightclubs with exotic dancers. But he confidently told Romano, “It would take an hour-and-a-half to learn everything there is to learn about missiles,” adding, “You know who really wants me to do this? Roy.”

Roy Cohn gets what Roy Cohn wants. That’s the lesson Trump learned too. Why stop at nuclear arms negotiator when you can be president instead?

Since we entered the coronavirus pandemic phase of the Trump presidency, my Roy Cohn antennae have been picking up signals daily.

When health care workers in my home state of New York were on their knees begging for masks and other protective clothing, President Trump suggested that maybe the problem was these items were “going out the back door.” Later that same week, from the storied Rose Garden at the White House, Trump repeated his question, “Where are the masks going? Are they going out the back door?” This is the language of organized crime, of the mob. Before Cohn connected Trump to the Reagan White House, he introduced him to the biggest crime bosses in New York City. It was Fat Tony Salerno who made sure, in the midst of a strike by concrete workers, that the building of Trump Tower could continue uninterrupted.

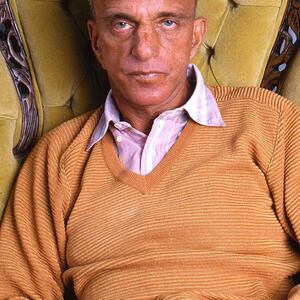

Roy Cohn and Donald Trump

HBOIt’s not PPEs mysteriously slipping out the back door that is criminal—it is Trump’s carelessness with American lives, especially the lives of the poor and disenfranchised, many of whom are people of color.

Lois Romano recently discovered she’d saved the tapes from what was one of the last interviews Cohn gave before his death in 1986. In them, we can hear a fading Cohn who cared about his legacy, who hoped that people might remember him as tough but “basically a good guy.” Romano asks, “But what about those who say you ruined people’s lives?” Cohn shoots back without pause, “I say name one.”

So yes, I’m still talking about Ethel and Julius Rosenberg because of Roy Cohn, and we’re still talking about Cohn because of Trump.

The tough-guy stance of both Cohn and Trump masks the deep fear familiar to racists, misogynists, homophobes, liars, and cheats everywhere. As we watch in horror, Trump’s Cohn-like response to the pandemic has resulted in countless more lives lost. And, in the process, as it has been throughout his presidency, our democratic ideals, our constitutional protections, our dignity, and our humanity are disappearing out the back door.

Ivy Meeropol is the director of the documentary BULLY. COWARD. VICTIM. The Story of Roy Cohn, premiering June 18 on HBO.