It’s only a few minutes into the interview and I’m already being chastised.

“This may sound hostile, but my work isn’t about gay life. Period. It’s never been.”

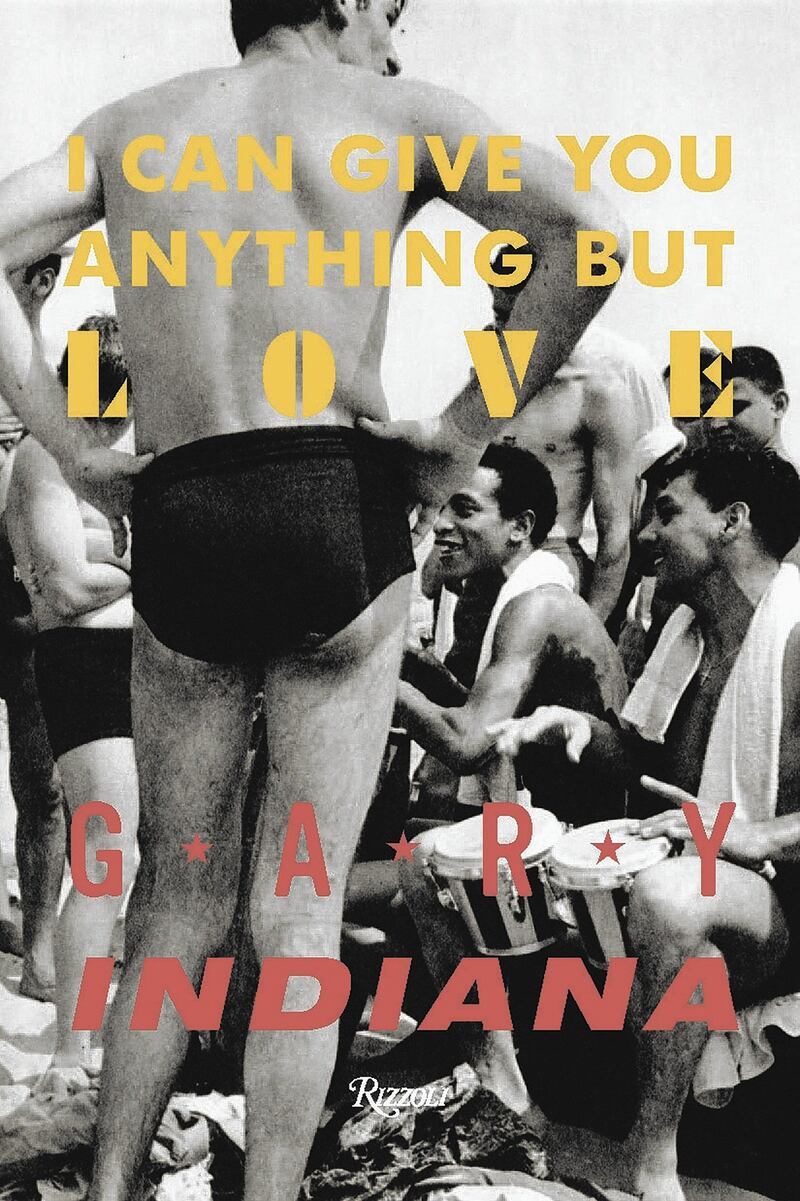

You see, I’m interviewing essayist and novelist Gary Indiana about his delightful new book, I Can Give You Anything But Love. I read the book, and am interviewing him, as gay man interviewing somebody I consider a renowned gay writer.

ADVERTISEMENT

But Indiana is having none of it.

As he points out in the interview, his oeuvre, which includes two of my favorites, Horse Crazy and Three Month Fever, is not just writing about gay themes. In our talk, Indiana expounds at length about everything from the political situation in Turkey (he has recently fallen in love with the country) to that here in the U.S.

At 65, he sits across from me in the top floor of the IAC Building in New York City. He is slight in person, and while older than the man in the book I just read, his eyes are what draw you in as they alternate from lighting up solicitously when he’s excited to flashing dangerously when annoyed. When he hesitates, it is not because he is unsure of what to say, but because he is about to uncoil and unleash a torrent of something—vitriol, compliments, explanations. And he giggles. Sorry, but there is no better, albeit less serious, way to describe his laughter. Oh, and he pays close attention to how societies treat their cats.

There is perhaps another—and very understandable—reason for Indiana’s aversion to that label. As he points out, when you’re tagged as a gay writer, you find yourself relegated to the less trafficked LGBT section of the bookstores.

I Can Give You Anything But Love traces a faint outline of Indiana’s life, stopping here and there to dwell on particularly memorable places and people. In fact, as I point out to Indiana, in fairness to me the childhood section races right to: “First blowjob: Paul Carlisle. His skin’s dark for a Caucasian but his family’s considered white. He has the biggest hard-on of any boy at St. Thomas Aquinas School, it’s well known. I suck him off all through seventh grade.” Just a few sentence into the book is, “At first I couldn’t tell if he was Abdul or another mulatto who boned me a few times a thousand years ago, when the skin market assembled at night by the Fiat garage on the Malecón.”

He grew up in New Hampshire, in “a backwards town in a backwards time. Nothing prepared me to be in a city or being gay.” The book follows him to those cities, in particular San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York, with chapters about his visits to Cuba interspersed. The Indiana of New York (where he still lives) is perhaps the best-known but least written about in the book.

San Francisco was where he began a “different” path: dropped out of Berkeley, offered his body for rent, and got involved with the porn industry. You name something counterculture, he probably did it.

“We went everywhere in a posse,” he writes in one typical passage. “Collecting rootless, powerful, attractive, emotionally flattened hippies of both sexes, who were soon employed on the psychedelic fringe of the porn business.”

The next stop was Los Angeles, and the book continues its heady swirl of highbrow references and lowbrow experiences. In the span of two paragraphs, he talks about reading The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich and how in his personal life, “I pick up a new person every night. This procedure is fraught with insecurity about my attractiveness. My willowy, fey look passed out of fashion a while ago, when the androgynous template slowly butched up during the disco era, becoming the present macho clone craze.”

That passage, however, is part of Indiana’s genius, and what made me want to talk to him as a gay writer. A reflection on his own long and tortured sexual past (about which, he tells me, he was “dimwitted” but “I don’t have any regrets”), it’s also an incisive observation born of experience, about that unfortunate shift in gay history that has led us to the insufferable profusion of clones now found in Los Angeles, Rio, Barcelona, Instagram, everywhere.

“I thought of Los Angeles later as a city of false starts, first paragraphs, broken-off beginnings of things that never proceeded,” writes Indiana. In our interview, Los Angeles is given similar short shrift. But it seemed to me that Los Angeles, despite his frustrations, helped mightily to create the Indiana we love—the Indiana who mercilessly skewers our fascination with celebrity.

The signature anecdote from the L.A. section concerns a job he once had at the Westland Twins cinema: when actors such as Anjelica Huston or Tony Perkins came in, he “sometimes asked for their autographs on dispenser napkins, then took somewhat childish pleasure in using the napkins to mop up Coke spills.”

But it is Cuba that dominates the book. Cuba, with its raft of contradictions, quirks, and endless stream of flesh, matters the most to Indiana. Unsurprisingly, he tells me he’s afraid of what the hordes of American tourists will do to it. The Cuba of Indiana is how one imagines the Tangier of Burroughs. There is something freeing about a world of easy sex with endless hot men, but also something incredibly sad and reminiscent of what Voltaire said about women in Paris: “respected when they’re beautiful and thrown into the garbage dump when they’re dead.” But Cuba is where Indiana also finds the closest he’ll come to what society would call acceptable love with Ricardo.

The joy of reading Indiana is that he is largely fearless when it comes to saying what he thinks about a person, regardless of their fame. While in person he has an aversion for name-dropping, his pen knows no such constraint.

“I disliked David Lynch immensely. His stories were humorless and boring. His smarmy air as he stirred his Postum was even creepier than his movie.”

“Hemingway is a lousy writer. A phony writer. A writer whose books are a tissue of falsehoods and moronic clichés of masculinity. A mendacious, ridiculous, deluded buffoon of a writer intoxicated by fame to the point of writing drivel.”

While he credits her with “the mind of a steel trap,” he writes that “the irksome repetitions and overly precious one-line paragraphs in Didion come directly from Hemingway … The tough, laconic, manly men who serve as fantasy heroes in Didion’s fiction have the unmistakable Hemingway touch. So do the shrieking pansies and suicidal homos she scatters through her books for spice, like pineapple rings on a Christmas ham.”

In fact, there is often a disconnect between the Indiana of the pen and the man sitting across from me. While his private life is laid bare in the book, he tells me, “Despite what people think, I’m an extremely private person” who felt uncomfortable writing the book. While Indiana’s world view may not mesh with the current one being promoted by the gay community—he says “nobody wants to fuck the same person for more than two years,” disdains how “everybody wants to be normal, and everybody wants everybody else to be normal,” and that we’re “more conformist than the McCarthy Era”—it’s an important voice to be heard.

And while he may not fully accept it, Indiana has been there and done that when it comes to the vertiginous past half-century of gay life, and there are few other pens I’d rather have chronicling it.