Documentaries about the modeling industry are apparently en vogue.

Not only will Apple TV+ debut The Super Models—a docuseries about the A-list posse that dominated ’80s and ’90s runaways, including Christy Turlington, Linda Evangelista, Naomi Campbell, and Cindy Crawford—next week, but there are two other new docs that celebrate pioneering, largely unsung titans in the fashion world.

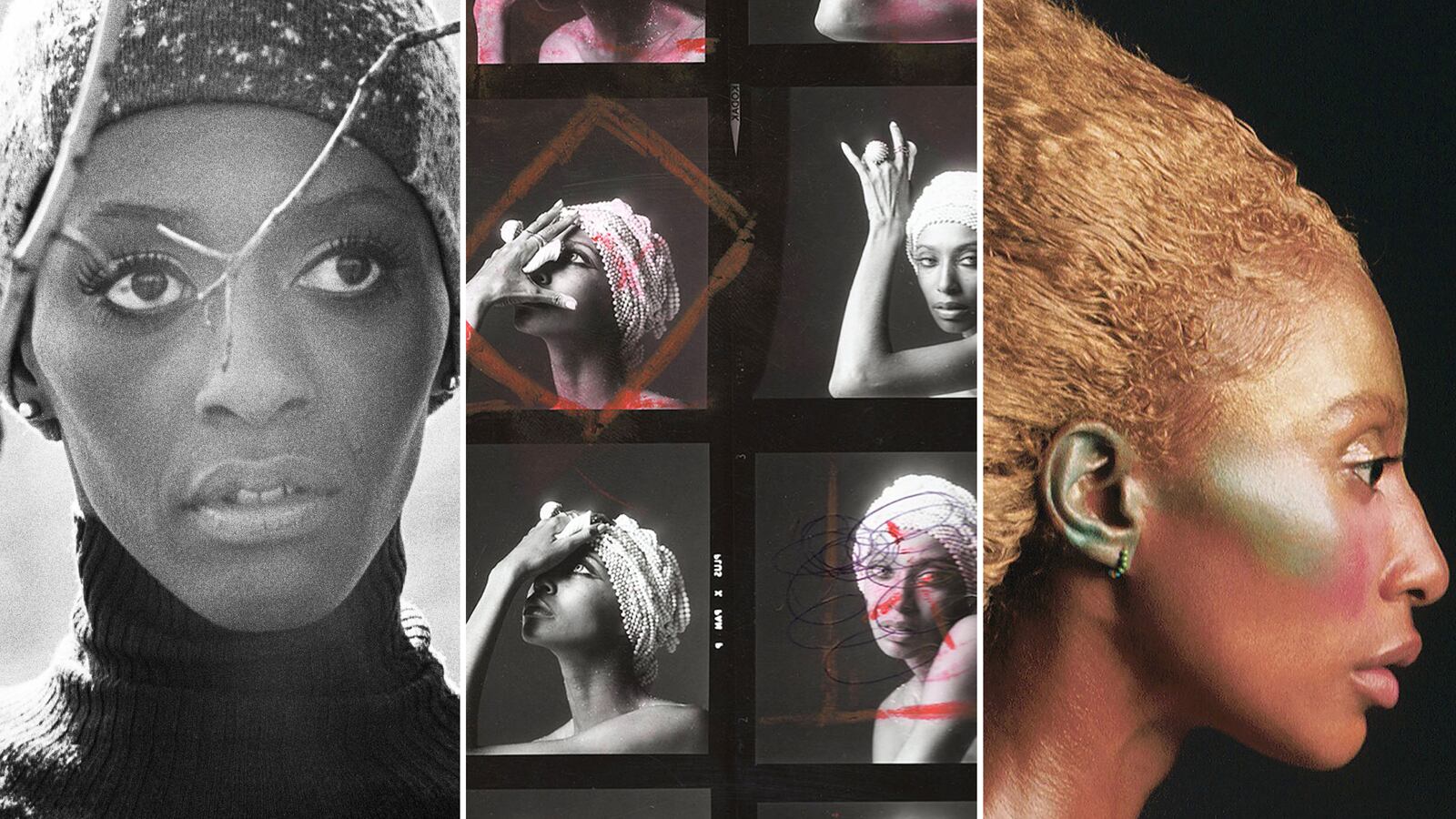

On Wednesday, HBO dropped Donyale Luna: Supermodel, about the inscrutable figure who in 1966 became the first Black woman to appear on the cover of British Vogue. And on Friday, Magnolia Pictures released Invisible Beauty, a film exploring the career and activism of 1970s model Bethann Hardison. The two films approach their complicated subjects in different ways, but each offers a rich analysis of the politics of beauty and the loneliness of being a trailblazer.

In the charming and riveting Invisible Beauty, Hardison serves as a co-director and an insightful narrator of her storied biography. The 80-year-old Brooklyn native bluntly retells her breakthrough at the 1973 “Battle at Versailles,” where the top French and American designers went head to head on a runway, boosting the profiles of several stateside names. The fabulous face-off also gave a spotlight to an atypical number of Black models at the time, including Pat Cleveland, Toukie Smith, Billie Blair, and, of course, Hardison.

Compared to her brown-skinned peers, Hardison considered herself the first “Black-Black-looking” model with especially dark skin and a short afro, something that made her success feel even more extraordinary. Her New York companions, including Fran Lebowitz and fashion designer Stephen Burrows, attest to a kind of charisma and confidence that instantly won people over.

Still, Hardison always understood that her unique opportunities—while other models who looked like her struggled to break into the industry—were deeply unfair. In response, she founded the Bethann Management Agency, which represented famous Ralph Lauren model and male video vixen Tyson Beckford, among others. Later on, in 1988, she started the Black Girls’ Coalition, along with friend and fellow model Iman, which transformed from an organization celebrating emerging Black talent—including Naomi Campbell, Tyra Banks, and Cynthia Bailey—to more of a watchdog group, as Black models reported substantially lower pay than their white peers. In 2013, she sent an open letter to designers condemning their exclusion of Black models after fashion journalists reported on a wave of Eastern European women dominating the runways.

Bethann Hardison with the 1991 Black Girls Coalition

Oliveira Toscano / Courtesy of Magnolia PicturesHardison’s participation in the film spares the audience a tedious history lesson, as the model and activist offers her witticisms and observations about humanity (“The lighter the load, the freer the journey”; “I don’t think people change, I think they just become more of who they are”) throughout the film. One of the most fascinating parts of the documentary involves a present-day storyline where she and her son, actor Kadeem Hardison, have a falling-out. From Kadeem, who played Dwayne Wayne on A Different World, we learn that Hardison was a tough mother who had a tough time connecting with her only child. Footage of Hardison mentoring younger models, though, shows a nurturing side of her that she couldn’t give to her own offspring, and one can infer a resentment of Kadeem’s privileged upbringing.

You can also theorize that the fashion icon was spread too thin by her career, constantly having to look after others without having an elder to look to for guidance herself. As much as Invisible Beauty tells a triumphant story, it also makes being a trailblazer look downright exhausting.

A more difficult biography to swallow is Luna’s—not simply because she’s no longer around to tell her own story, but because even the people closest to her seemingly had no idea who she really was. Born Peggy Ann Freeman, the six-foot-tall Detroit-born model started self-mythologizing at a young age. Luna’s younger sister, Lillian, tells us that the model’s awkward but imposing beauty wasn’t appreciated by her Black schoolmates, even though her light skin earned her the designation of being “pretty.” She considered herself an outcast, and began going by her exotic professional name and even adopting a vaguely European accent that she maintained throughout her career. Additionally, she would tell her classmates she was multi-racial, claiming a new non-Black ethnicity each time.

We learn that Luna’s active imagination may have been a trauma response to growing up in a violent household. After she left the Midwest for New York, her mother had shot her physically abusive father out of self-defense. In the era of segregation, it was probably easier for Luna to capitalize on her light skin and “exoticness,” which she was immediately recognized for in the modeling world. Likewise, the documentary can’t help but paint a “tragic mulatto” narrative for the model, who was stuck between two worlds and ultimately couldn’t find a place to call home.

For instance, Luna fled from New York to London in the late ’60s after white readers objected to her numerous appearances in Harper’s Bazaar. Initially, it seemed like a better place to live than the U.S., as she was warmly embraced by an artistic, mostly white crowd, including the Rolling Stones and Salvador Dalí. But it’s hard to tell whether her British peers, or any white people for that matter, saw her as a human being and not just a fascinating object to gawk at—which is arguably how she’s spoken about by several talking heads. Given that one of the white men interviewed, British photographer David Bailey, casually refers to her as “negroid” in the documentary, you get the sense that Europe’s interest in her image didn’t necessarily translate into respect for her as a Black woman.

Likewise, we hear many heartbreaking diary entries, read by Luna’s daughter Dream Cazzaniga, where she laments her feelings of unwantedness and isolation. The documentary is, in part, Cazzaniga coming to terms with the most important person in her life whom she’ll never truly know. (Luna died of a heroin overdose in 1979, 18 months after Cazzaniga was born.) It’s devastating seeing Cazzaniga inherit her mother’s feelings of disconnectedness, but satisfying to watch her collect fascinating details from Luna’s life, the most vital being that she did subtly change the fashion industry—whether she could perceive it while she was alive or not.

Overall, both documentaries are refreshing in that they paint a truthfully ugly portrait of the fashion industry—albeit one that doesn’t touch on the obvious fatphobia that pervades modeling. (Supermodel indirectly touches on colorism.) Still, in a time when every brand is patting themselves on the back for inclusivity, the sacrifices that had to be made for that to become an expectation should not be forgotten. Both films make sure viewers don’t forget.