In December 2019, police in Rexburg, Idaho alerted the media: Two children had gone missing, along with their mother, Lori Vallow, and her new husband, Chad Daybell. No one had any idea where they were. Quickly, speculation swirled—that maybe their disappearances, and their whereabouts, could be linked to the “cult-like” religious beliefs held by Vallow and Daybell. Both were avowed members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Daybell had found a small amount of celebrity within Mormon circles for authoring LDS fiction and running his own book publishing company. But both Vallow and Daybell also entertained ideas at the fringes of the Mormon faith—ideas that weren’t acceptable to talk about in church on Sundays. They held study groups and scrutinized the works of “near-death experience” authors who claimed to have died and come back to life with knowledge from “beyond the veil.”

Much has been discussed about Lori Vallow: the gorgeous mother and former beauty queen whose children went missing. But in When the Moon Turns to Blood, author Leah Sottile also examines how Daybell grew up in the mainstream LDS church in Utah, and when, exactly, he started to entertain beliefs that aren’t Mormon at all. In the book, she tells the story of when he decided he might not merely a man from a small Utah town, but a seer and a revelator who could predict the future.

After sundown, the peaks of the Wasatch Front fade into a darkening sky, and everything in Springville, Utah, becomes the music of crickets, all together sawing a twilight song.

Today, most of the houses in Springville are tight brick squares. The street where the writer Chad Daybell grew up is an avenue of brick homes with well-tended gardens, and American flags, and basketball hoops, and potted plants on porch steps.

Springville is a small city but hardly sparse: it has more than one grocery store, a McDonald’s, a Taco Bell, a pizza place, a sub place that makes its sandwiches on rolls the texture of pizza dough, and a drive-through soda shop. In 2020, the population was just over 35,000, and there were 18 Mormon churches. As the LDS population of Salt Lake City has declined, according to the Salt Lake Tribune, Mormonism has risen here in Utah County. Some 80 percent of residents identify as LDS.

Death is a theme that runs prominently through almost everything Chad Daybell ever wrote, from elementary school papers to articles he penned while on staff at the Daily Universe, the student newspaper at Brigham Young University. It is hardly the only topic he covered, but it is one he often wrote about in a deeply personal way.

This fixation started when Chad was a boy. In fourth grade, he authored a novel titled The Murder of Dr. Jay and His Assistant. “It was a fun story— despite the gruesome title.” His teachers praised his creativity.

In middle school, Chad was bullied, and he wrote of how much it confused him. “I was basically mad at the world,” he said in his memoir.

One day, on his walk home, he cut across a large green park near the Daybell home. “I saw a honeybee pollinating a dandelion. I peered at it for a moment, then smashed it with my shoe,” he wrote. He felt pathetic. He kept killing bees anyway.

“I spotted another one, then another one. I got a strange satisfaction from it. I kept count, and after about a half hour I had killed 120 bees.”

He only stopped killing the bees when a voice told him to stop.

The Voice.

While death is the theme running through all of his works, The Voice is the most common recurring character in both his fictional stories and nonfictional recollections. And while it is not uncommon in LDS culture to refer to a spirit that speaks personally to a believer, in his memoirs Chad writes of a voice that whispers and sometimes even shouts instructions into his ear. It scolds him. It reminds him when he’s gone astray. Sometimes it is distant, giving vague directions, like the Caterpillar in Alice in Wonderland. Other times The Voice arrives with extremely specific instructions: militaristic commands that render Chad powerless.

He never disobeys The Voice. Never.

On a warm August day in 1985, when Chad was 17 years old, he stood on the edge of a sixty-foot-tall cliff at Flaming Gorge Reservoir in northeastern Utah, about to take a leap that he believes changed the entire trajectory of his life.

At the exact second his feet left the earth and his body dropped toward the water, it was as if a door opened below, and he fell right through it. Into another place. Into another dimension.

When he hit the water, “It felt like I had slammed into concrete,” he recalled. “A shock went through my entire body and I saw a flash of white light. I felt an audible pop at the base of my skull, and I thought, ‘Oh no, I broke my neck.’”

At the top of his skull, he could feel his spirit exiting his body, spilling out through the crown of his head but getting snagged in the process. It was unable to fully detach from his skull. As the world fell away from him, a new one around him was opening—like a giant eye waking from sleep, and he was its pupil. This was “the other side of the veil,” where Chad saw “an endless white plain” spreading in all directions. There was music. It was warm.

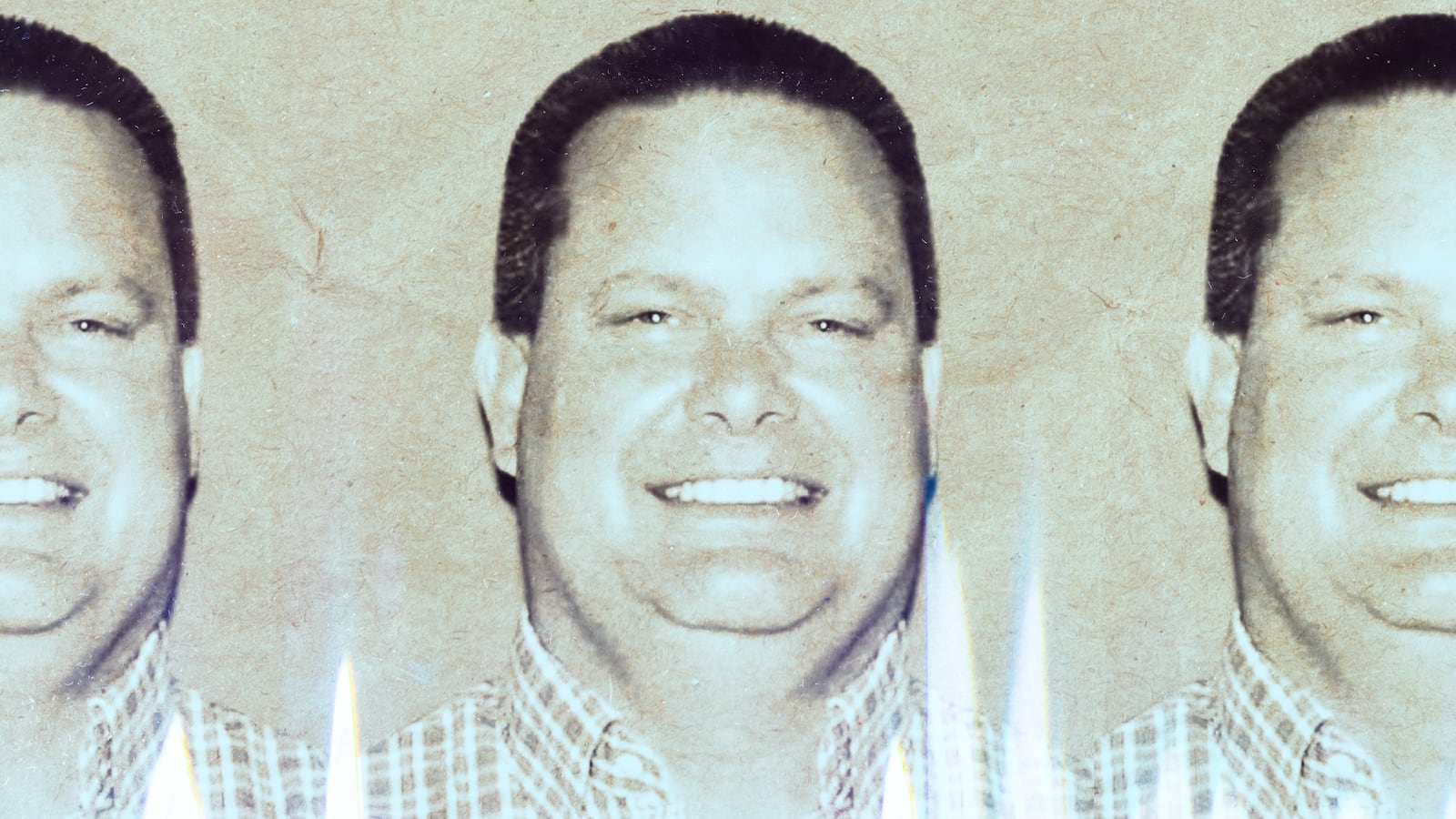

Lori Vallow Daybell and Chad Daybell.

MCSO/Rexburg Police DepartmentA friend swam out and pulled him to safety.

For a week afterward, the jump stayed with him. “Sometimes my right eye would just go blind, but if I hit the side of my head with my palm, I could see again.” He didn’t tell anyone of this out-of-body experience or the plain of whiteness he’d seen. He believed that when he hit the water, he had been transported somewhere else.

(Years later, in 1999, a 19-year-old died cliff jumping at Flaming Gorge, and in 2013, a man died after a group of his friends were unsuccessful in dissuading him from jumping from a 175-foot cliff there. Signs now warn against cliff jumping in the area.)

Chad considers that jump to be his first “near-death experience,” or NDE. As he explains in his memoir Living on the Edge of Heaven, after the jump he became unexplainably interested—“like never before”—in a very specific subculture of the LDS Church. He wrote that he became transfixed by the writings and teachings of W. Cleon Skousen, a man who would promote a hyperparanoid constitutionalist conservatism to Mormons, linking faith with fear, professing a belief that the LDS people were the fabled ones in the White Horse Prophecy.

Despite his near-death experience, life as usual resumed for Chad. At Springville High School, he was known as a quiet and funny high achiever: he played baseball, and his good grades landed him in the National Honor Society. He served on the student council as treasurer and won a scholarship to Brigham Young University, where he planned to study journalism.

He made friends with other boys who liked basketball just as much as they liked studying scripture. Chad and a distant cousin, who was also his classmate, would drive around Springville talking. “People probably thought we were looking for girls, but in reality we were discussing the Plan of Salvation,” Chad wrote. “We were basically gospel nerds.”

During his first year at BYU, Chad was unlucky in love. Once, when he was on a date with a girl from Florida, she remarked that he was too sheltered. “Sorry,” he recalled her saying, “but you need to get out and see the world. There’s more to life than Utah Valley.”

It offended him. “I’d been to Disneyland three times with my family, and one time, I’d walked about a mile into Tijuana, Mexico. Then there was the trip to the Four Corners Monument where I’d stood in four different states at the same time! What did she mean I hadn’t seen the world?” It’s hard to tell if he’s joking.

Perhaps because of this remark, a year into college, Chad decided to file paperwork to serve a mission early, and he was accepted. (Many young Mormons serve as missionaries, fanning out around the United States and the world to spread the gospel of the LDS Church for up to two years. In 2021, the LDS Church estimated that more than 53,000 missionaries were serving missions.) By the time he embarked on his mission, Chad had read the Bible nine times and the Book of Mormon eighteen times. “Most kids, they read the Book of Mormon once and maybe the Bible,” his brother Brad Daybell said. “You could ask him anything, and he would know the answer.”

He embarked on a two-year mission in New Jersey. It was a world away from Utah, the only place he’d ever known. During his first week there, another missionary snapped a photograph of Chad sitting atop a fence with the Hudson River and the World Trade Center towers in the background. He’s smiling, wearing a baggy white dress shirt and a straight black necktie, and holding a book.

The remains of Joshua Vallow, left, and Tylee Ryan were found buried on Chad Daybell's property.

Rexburg Police DepartmentThe experience was enlightening for him but also confirmed his biases about big-city life. By his telling, New Jersey was a torrent of sirens and insults, watching cars burn and people shattering store windows in broad daylight. Chad claims to have had a gun pointed at him once. Maybe he was not a worldly man, but it seems Chad was content to understand the world from Utah, a place where men like him dominate everything, men whose worldview is the prevailing one, whose religious beliefs dictate life and laws.

After New Jersey, he came back home to Springville and BYU and set out on a new mission: finding a wife. One day, he flipped through his younger brother’s Springville High yearbook and noticed a girl in a white V-neck dress, with a thin gold chain around her neck, her light hair cut into a pixie, like Winona Ryder or Jamie Lee Curtis. Her name was Tammy Douglas.

At a Singles Night held at a local LDS building, Chad noticed Tammy across the gym, on the other side of a volleyball net. She caught his eye. “I’m going to spike it in your face,” she said. He loved her immediately.

When Chad and Tammy were engaged the day before Thanksgiving 1989, they chose the local cemetery in Springville for their photos. After Chad returned home from his mission, he took a job digging graves in the cemetery managed by the local Parks Department. Tammy, it turned out, worked in the Parks Department as a secretary, and after their encounter at the volleyball game, she started hand-delivering burial reports to the graveyard, hoping to catch Chad on his shift.

Death was the backdrop of the time they fell in love. Their favorite song was the Smiths’ “Cemetry Gates” from their 1986 album The Queen Is Dead.

In one of their engagement pictures, Tammy stands to the right of a tall gravestone, wearing a chunky white sweater and light-colored pants. Her left hand is propped at her brow, as if she is trying to see far off into the distance. Chad peeks out from behind the stone, to its left, wearing a jacket and a tie. He looks up toward his fiancée. They’re both smiling, like they’ve been laughing, like this place makes them happy.

The novelty of his job was not lost on the aspiring writer in Chad, who made it the subject of his first memoir: One Foot in the Grave.

Published in 2001, the book is presented as something of a how-to guide to getting along with the person digging a grave for your loved one—a rather specific niche. But it also provides a window into his personality. The man writes with a sort of golly-gee sense of humor, cracking jokes that are so tame you couldn’t even call them dad jokes. He is dopey and boyish, trying to bring humor and levity to a place that carries so much baggage, peeling back the curtain on a job that few people understand. In some ways, he’s just like anyone in a graveyard at night: spooked easily by noises.

Shortly after completing his degree at BYU, Chad decided to apply to graduate school. He recalled sitting down, pen in hand, to fill out the application, only to be interrupted by The Voice.

“This is the wrong direction for you,” it said. “You won’t need additional schooling to accomplish your life’s mission.”

He immediately threw the application in the recycling bin.

In 1993, Chad was working as a copy editor at the Ogden Standard-Examiner, and he and Tammy relocated to Ogden, a little over an hour north of Springville.

That March, the newspaper ran an interview with a woman named Betty Eadie, who claimed to have had a profound near-death experience while recovering from hysterectomy surgery, which she wrote about in a book called Embraced by the Light. In her book, she describes dying in the hospital, hovering above her body, and a flurry of activity from doctors. She passes into another realm, where she sees Jesus Christ. A board reviews her life and tells her it is not her time to go.

In a way, Eadie’s book mimicked the common language used by people who claim to have experienced an NDE: the feeling of floating over one’s body, the warm light, going to another realm, and a rapid recollection of one’s entire life—like a slideshow in fast-forward.

In her 1993 interview with the Ogden newspaper where Chad was working, Eadie claimed that her experience caused her to return to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, of which she had become an inactive member. Beyond the veil, she believed she had been told the LDS faith was “the truest Church on the earth.”

Embraced by the Light saw immense popularity in Utah, and Eadie became a star. The book also skyrocketed on The New York Times bestseller list. When Eadie spoke at a high school north of Salt Lake City, thousands of people came to hear her speak. Traffic jammed up the freeway for miles, with drivers abandoning their cars and walking to the event. Police were called in to control the crowd. “Finding herself stuck in the gridlock,” read an article on the chaotic scene in the Davis County Clipper, “Eadie rolled down her car window and asked someone what all the excitement was about, and why there were so many cars. ‘Everyone is going to see Betty Eadie,’ she was told.” Eadie was 40 minutes late to her own event.

In the Ogden Standard-Examiner interview, Eadie explained that the book’s popularity was in part because “it speaks to people who have had similar near-death experiences and it reassures people of an afterlife.” She wasn’t trying to become a “prophetess” or start another sect of Mormonism. She was just telling her story.

But Embraced by the Light also proved that the business of disclosing an NDE was a potentially lucrative one.

In 1993, Chad and Tammy took a vacation with his side of the family to La Jolla, California. One day at the blue-watered beach, he and his youngest brother, Brad, ventured out onto rocks that had been exposed during low tide and poked around for shells. The tide started coming in closer. Brad retreated to the beach, but Chad stayed out on the rocks too long.

As the force of the Pacific threatened to overtake him, The Voice was in his ears again. “Get down and cling to that rock!” it commanded. Chad did as he was told. The ocean crashed all around him. “The force was incredible,” he wrote. “It took all of my strength to not get ripped away and tossed around.”

Something else happened, though exactly what isn’t clear. Perhaps the waves slammed his skull into those rocks. Perhaps he started to drown. In his writing of the event, Chad described being immersed in salt water, barely hanging on to safety and consciousness. He writes that he was “in the proverbial tunnel of light” and felt a warm, soft embrace all over his body. Two male figures appeared above him—his pioneering Utah ancestors. The men asked if Chad would agree to a series of tasks. He told them yes.

“I was suddenly back in my body,” he wrote. Chad tumbled toward the shore, and his family, who’d watched in horror as he struggled, rushed to his aid. He was covered in blood. They brought him to the hospital for stitches.

Chad believed it was a continuation of the earlier NDE he’d experienced as a teenager. This time, he saw “beyond the veil,” as he often refers to it, and into a spirit world.

“My personal veil had been ripped open even wider, and this time it didn’t close up nearly as much as it had after my Flaming Gorge experience,” he writes.

From then on, The Voice kept coming. Prodding him, herding him like a sheepdog to a flock, dictating his direction, and presumably ensuring he stayed true to the promise he made that day, when the force of the ocean bore down on his body.

For a time, he stayed quiet about what he believed had happened. But by the mid-2000s, Chad was out and proud about his belief that he had special access to the spirit world.

But his youngest brother, Brad, remembered that day at the beach in La Jolla a little differently. There on the rocks, the water kept getting closer and closer. “And then a huge wave came out of nowhere and hit us both up into the rocks,” he recalls. Brad was able to hold on, “but it kind of sucked [Chad] back out, and then threw his body into the rocks, scraped up his back.” They did take him to the hospital, but he’s not sure about the rest.

“I mean, it was intense at the time,” Brad said. But at no point did his brother tell him he had lost consciousness or had any kind of near-death experience. “I hadn’t heard anything about that—his experience—until way later.”

Brad knew his brother Chad was “obsessed with the near-death experience stuff,” he told me. “But he never mentioned he had his own.”

Afterward, Chad wanted to tell stories of near-death experiences, to be open and honest with the world about the images he was seeing in his head because of his supposed access to the spirit world beyond the veil. He started to believe his visions were divine ones, revelations shown to him by God.

Excerpted from When the Moon Turns to Blood: Lori Vallow, Chad Daybell, and a Story of Murder, Wild Faith, and End Times ©2022 Leah Sottile and reprinted by permission from Twelve Books/Hachette Book Group.