On Wednesday, January 3, the Senate returns from their winter break, and to the chagrin of Roy Moore, who is yet to concede the Alabama senate race, Doug Jones will be sworn in as the new senator from Alabama.

The Democrats will start of the year with a new seat in the Senate – the GOP now only has a 51-49 majority – and strong chance of retaking the Senate, and possibly the House, in 2018. However, despite the momentum generated from Jones’ victory and Ralph Northam decisively winning the governorship in Virginia, both of these candidates have already made statements that have frustrated Democrats, tempered the excitement surrounding their victories, and potentially harmed the party’s momentum in this pivotal year.

Less than a week after narrowly defeating Roy Moore in the Alabama Senate race, Jones had already broken ranks with the Democratic establishment.

He told CNN’s Jake Tapper that he does not believe that Trump should resign over the sexual harassment allegations against him, saying, “Those allegations were made before the election, and so people had an opportunity to judge before that election.”

Given that Jones campaigned on what was for Alabama a pretty liberal platform, many progressives hoped that he would take a tougher stance than essentially reiterating the White House’s talking points.

Likewise, Northam, who supported Medicaid expansion during his campaign, has already criticized the cost of the program and said that he would like to see “managed care” reforms to supposedly make the program more efficient.

These positions run counter to their campaign messaging. And to further inflame progressives, they have also stressed the importance of bipartisanship.

During a previous era, calls of bipartisanship from a Democratic politician might have been welcomed by progressives, but not today. Today’s Republicans craft legislation in secret refusing to work with Democrats, and they create laws that limit access to the vote for Democrats. Bipartisanship today is largely not about finding a way to meet in the middle, but instead acquiescing to and tacitly emboldening Republican obstructionism. So when Democrats, especially those in the South, attempt this tactic, they are basically undermining progressive values in order to work with a party that shows no desire to work with them.

Jones and Northam haven’t even been sworn in and they have already undermined their progressive credentials. The Democrats are worried about the type of politicians these two will be, and they should be. These two will probably be way more conservative than progressives would like, but above all else the disappointment that Jones and Northam may bring cannot result in Democrats staying home from the polls in the elections to come.

Southern Democratic politicians come from a school where bipartisanship and compromising with Republicans have been necessary for political survival. They appealed to the swing voters who could go either way, and they flipped some conservative voters, too. Yet as American politics has gotten more divided the pool of swing voters dried up, and Southern Democrats, at least white ones, all but disappeared.

So, I get that Jones and Northam earned their stripes in the political battles of yesteryear. Forming alliances with Republicans has always been their means of survival. (Northam actually voted for George W. Bush twice.) Their recent statements wouldn’t have even been a big deal a decade ago, but they are now. Instead of catering to middle, which may have been necessary three presidents ago, they need to cater to the left and especially the minority communities who helped propel them to victory.

In Virginia, record numbers of young voters and minorities showed up on Election Day. Northam won 69 percent of voters age 18-29 and 61 percent of voters 30-44. Voters 18-44 made up 38 percent of the vote. Northam also won 87 percent of the black vote and 67 percent of the Latino vote. These two groups made up 26 percent of the vote.

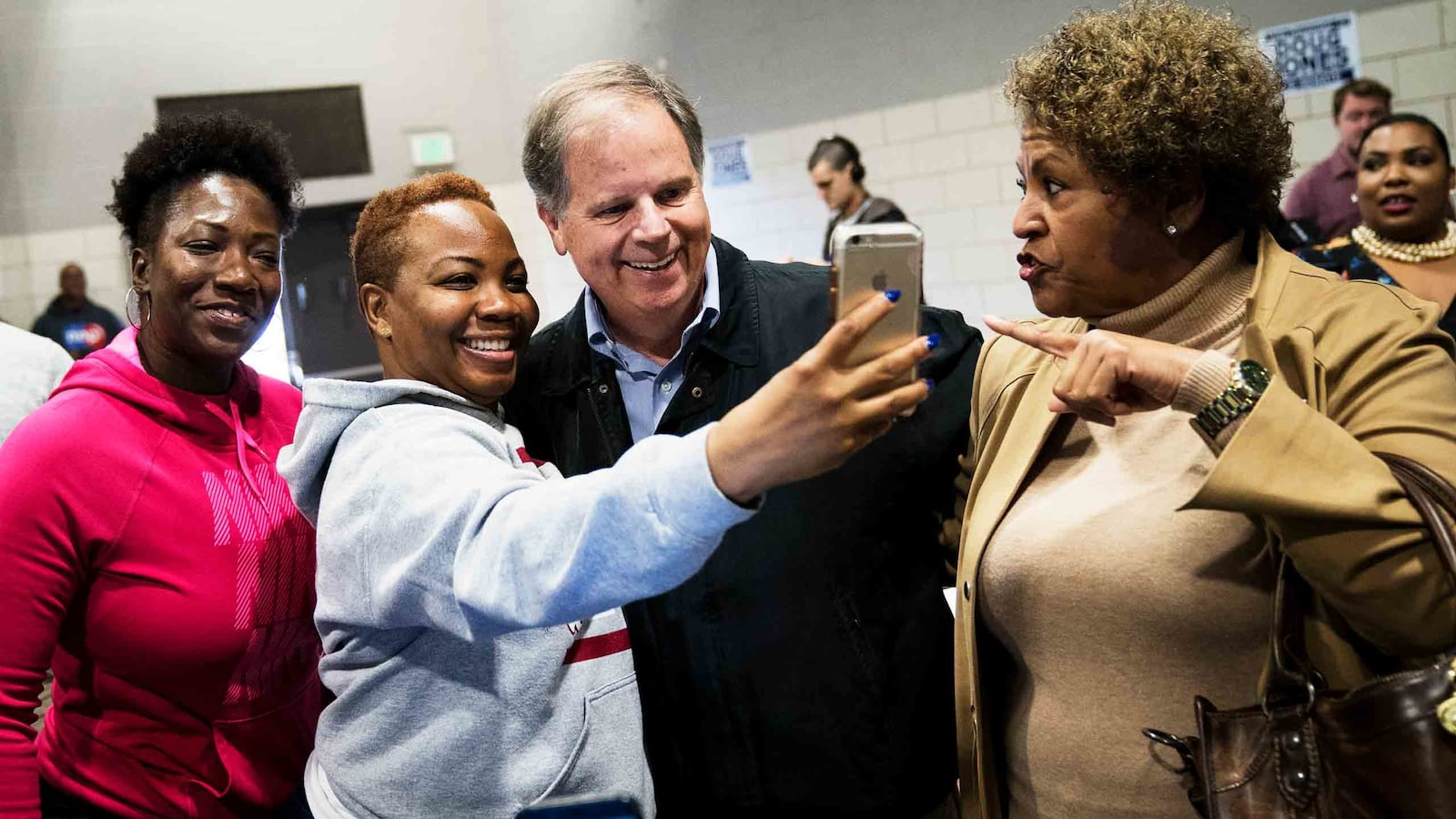

Young people and minorities put Northam over the top, and a similar story played out in Alabama. Leading up to the election, analysts anticipated that 20-25 percent of eligible voters would vote in the runoff election between Jones and Moore, but a surge in Democrat supporters, especially within the African American community, resulted in nearly 40 percent of eligible voters voting.

Black voters made up 29 percent of the vote in Alabama despite being only 26 percent of the population, and Jones won 96 percent of the black vote. Jones, who won by about 21,000 votes, got more than 300,000 votes from the African American community.

Jones and Northam get some slack because these sort of gaffes should be expected from Southern Democrats. But going forward minorities and young voters need to feel valued more than moderate Republicans by these two candidates.

In a state like Alabama, Jones may be hesitant to fully and vocally embrace the civil rights and voting rights positions of the African American community, out of fear of a backlash from the state’s Republican majority. But Alabama has turned disenfranchising African Americans into a science, and black voters did not come out and overwhelmingly support Jones so that he could turn a blind eye to his state’s racial oppression.

In this past election, Alabama even launched an “inactive” voter scheme – which may be unconstitutional – to further impair black voting in the state. It proved ineffective this time, but Alabama is relentless in its disenfranchising pursuits.

Likewise, Northam needs to recognize the how Virginia’s shifting demographics have made the state more liberal. More Virginians live in the north close to Washington, DC, and the black and Latino populations have become more influential. Neither of these groups needs a moderate Democrat who relies on striking deals with conservatives. They overlooked his support for Bush because a Democrat, any Democrat, would be better than Ed Gillespie, but they’ll need something more than a liberal who enjoyed the eight years of the Bush presidency.

Beyond voting rights issues, Jones and Northam might be unable to move further to the left, and while that may frustrate liberal voters, it should not impact their desire to vote in the future. So long as this new coalition of Democratic voters stays together and votes at similar levels, it will be able to win statewide elections. Jones and Northam might not be exactly the politicians progressives want, but these victories may have opened the door for progressive policies and candidates in the elections to come.