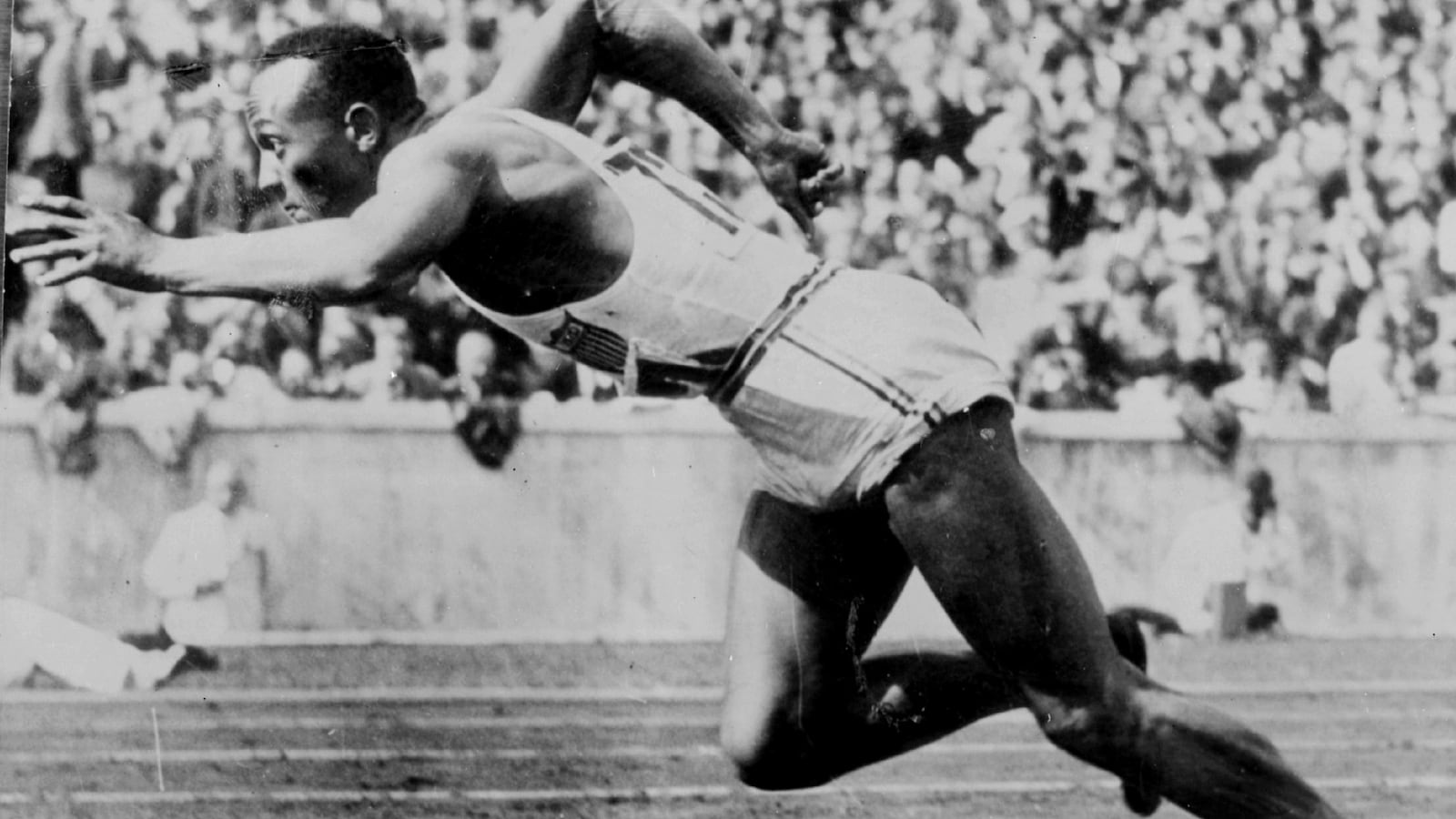

Decades ago, a 22-year-old black man rebuffed the aims of a racial supremacist. Under the gaze of Adolf Hitler, James Cleveland Owens—Jesse Owens—won four gold medals at an international competition intended by its host to showcase Aryan superiority: the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. This year marks the 80th anniversary of Owens’s triumph at those games.As children of Ruth and Jesse Owens, we have been privileged to experience the revival of our father’s Olympic accomplishments every four years. Over the years, we have been touched by—but also amazed by—how much our father’s memory endures. His achievements, even now, speak to the idea that desire, drive, and tolerance can outpace bigotry.His initial struggles at home after the Olympics also serve as a reminder that America was itself hobbled by narrow notions about race. He and his teammates returned with their historic success to a nation where blacks were second-class citizens; where he and our mother were forced to take a freight elevator at the Waldorf Astoria to attend a celebration in his honor. Stripped of his amateur status and trying to make a living in a pre-endorsement-dollars era, he took a variety of jobs to support his young family: Negro League baseball team owner, gas station attendant, proprietor of a dry cleaning business.The first president to acknowledge his achievements on behalf of the U.S. was not Franklin D. Roosevelt but Gerald Ford, when he awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1976. With that said, our father always believed in the good in people and that change would come. He steadfastly believed in the promise of America.As co-founders of the Jesse Owens Foundation, we have been dedicated to understanding the ways his legacy can continue to have practical meaning for young people, whom he championed.

For much of our lives, the three of us have lived, loved, and raised our families in Chicago. It breaks our hearts to know that it is a city that has become known for its street violence both among its citizens and those who are charged with keeping the peace.So it does seem timely to ask: What can people do—especially our young people—to put into practice the life lessons learned from our father both as a competitor and as a man?The questions of lesson and legacy are even more potent as a movie called Race, about our father, screens in theaters across the country. The film focuses on his arrival at the Ohio State University in 1934, his relationship to coach Larry Snyder, and his victories in Germany.Our father’s track and field achievements, while spectacular, don’t seem easily translated into daily lessons for the rest of us. Yes, he was disciplined, driven and believed in his speed from an early age. He had two coaches—Charles Riley and Snyder—who did as well. The vital force of mentorship remains a takeaway from his life, but in so many ways his athletic talent was singular.What remains quietly transformative are the things that came later, the things we knew intimately: his practice of good parenting and his and our mother’s emphasis on family and education. Together, they offered a steady regimen that could benefit us, our family, our community, perhaps even humanity.Ruth and Jesse Owens were a team. And they gave us a lot. Some things little girls wanted: Daddy would send flowers to mark special dates if he were traveling. He’d return bearing dolls, broaches, and charms from trips to India, Asia, Africa. Mainly, our father and mother gave us the things we needed: a sense of what matters. The drama and dance lessons, the modeling classes, they helped forge an awareness of self. Our father’s tireless work ethic and our parents’ emphasis on education bolstered our belief in self-reliance and connection.

Gloria was four years old when Daddy competed in Germany. Beverly and Marlene weren’t born until 1937 and 1939. Although the glittering hardware of his track and field feats were on display in our home, family conversations weren’t about his glorious past. When we sat around the dinner table, we discussed our day, how school was going, what we were learning. We knew the man as Daddy long before we were introduced to him as a legend who’d humbled (if temporarily) the Third Reich. Of course, we learned of his public stature as adolescents. When Gloria was in middle school, a classmate quipped that Daddy “has all his brains in his feet.” When Beverly arrived at college in the late ’50s, a fellow student asked, “Do you drive a Thunderbird?” Some assumed we’d have all these things because of who Daddy was.Even though our father traveled a great deal for his work as a good-will ambassador and speaker, our mother always made his presence felt. We knew he’d returned when we’d come into the house and hear the baseball game on. Those journeys abroad underscored a world of possibilities beyond borders, racial or national.These are not gentle times for young people. And it’s easy to imagine their suspicion that our father’s (and Jackie Robinson’s and Joe Louis’s) generation, although it experienced both virulent and nuanced racism, no longer offers a game plan for clearing the hurdles they face. Those family meals we had might seem like some African-American version of a Norman Rockwell painting. Yet, his legacy—his deep-rooted belief in one’s self—offers a touchstone.We felt lucky to have all the opportunities we had. Daddy worked hard to make sure that we had a good education. Each of us went to college. Marlene became the first African-American homecoming queen at Ohio State in 1960. Two of us attended graduate school. That was his dream and it’s reflected in how we’ve raised our own children. But he believed there are many ways besides getting A’s in a subject that help you move along in school, and move along in life.We are in our seventies and eighties now and we won’t pretend it’s not a hard row to hoe out there. There are times when the nation seems to take broad leaps back—not forward—in terms of tolerance and opportunity. Even so, if you don’t have the aspiration, education, or skills training, if you don’t dream and believe in yourself, success on whatever level you choose will be hard to achieve. “The battles that count aren’t the ones for gold medals,” he once said. “The struggles within yourself—the invisible, inevitable battles inside all of us—that’s what counts.” The records he set and expectations he shattered that week in August 1936 remain magnificent. Yet, we believe, it is this sense of personal best that makes his legacy timeless.