Cary Grant wouldn’t fall for just anyone.

But when he did, it was with all the grace and charm he had onscreen—and only to prove a very good point.

In Dyan Cannon’s new book, Dear Cary, which details their five-year relationship, the actress recalls one night that occurred after they were seeing each other for a few months. They were out for a walk after dinner, and while crossing La Cienega Boulevard, Grant, usually the picture of perfection, fell face-down in the street. He looked up at her, and asked, “Do you know how I feel about you?” She said no. His response: “Head over heels, that’s how I feel.”

Born Samille Diane Friesen in 1937, Cannon was a budding film star getting over a tumultuous relationship when Cary Grant came calling.

After spotting her on a TV show, Grant asked her for a meeting. She resisted, he persisted. Reluctant even to have lunch with the man, Cannon, whose nickname was “Frosty” in high school, writes, “Nice Jewish boys my own age—those I know how to handle. But a dashing, magnetic fifty-eight-year-old matinee idol with three ex-wives notched on his bedpost? I seem to have misplaced my instruction manual.” Cannon was unarmed, knew it, and forged ahead anyway.

She paints their relationship with a generous coat of nostalgia and many of their early months speed along like a breezy, joyous romantic comedy. She fakes chicken from La Scala as a home-cooked meal! He’s stung by a sea urchin, she pees on his leg! She teases him by pulling the keys out of his Rolls-Royce—while he’s driving—and chucks them out the window! Only 25 at the time, she’s dangerously young for him (there’s a 33-year age difference), and inexperienced in the ways of love.

Because she’s generous in her early descriptions of Grant, this can’t be billed as a “tell-all.” He’s charming at home, adorably eating the scraps from her plate (“my friends call me ‘The Scavenger,’ ” he says). And what of those gay rumors that have persisted for decades? In a phone conversation earlier this week, she says with a nudge nudge wink wink attitude, “I can tell you that we were too busy to even think about that. They talk about everybody in Hollywood … I never saw any indication of that. If that happened before or after me, I don’t know, but not while I was with him.”

Some of the fun of dating Grant is, of course, the star-studded supporting players around the whole affair. At a dinner party one night, Noel Coward confesses to her about Grant, “You know, I am wildly in love with that man.” She replies, “That makes two of us.” At a Halloween party at Alfred Hitchcock’s place, Jimmy Stewart sits on a whoopee cushion, and Hitchcock proposes Cary and Dyan make a film together. What’s not to love?

But here’s the rub: She wants marriage and a family, and their commitment tango lasts a few years. In one insightful moment, Cannon writes, “If Cary wasn’t going to budge, all I was doing was licking honey off a razor blade.”

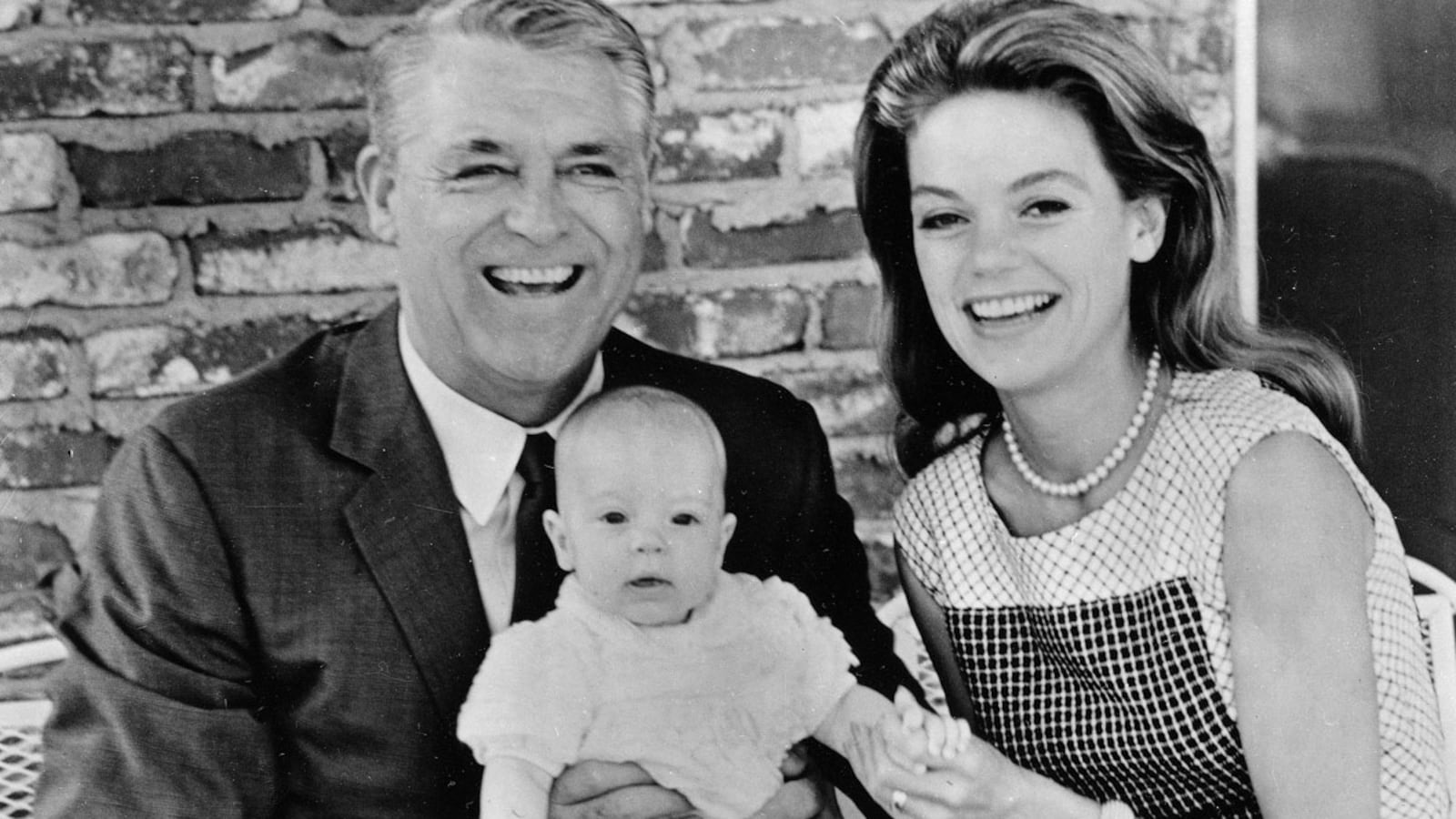

A few break-ups persuade Grant to commit, and they embark on a doomed marriage. Their daughter, Jennifer, is born just a few months after their wedding.

He was a tortured soul when they met. Or a recovering tortured soul. Grant told her early on, “I’ve swept out a lot of my dark corners. I’ve changed. It’s like I’m starting all over.” Much of his angst came from a complicated circumstance surrounding his mother, Elsie, whom he was told had been dead for 20 years. When he learned the truth—that she was in a mental institution—Grant was racked with misplaced guilt.

Sure enough, the happy memories fade for the couple, and the walls start closing in. “Slowly, he changed the way I dress, my choice of things, the way I wrote thank-you notes. He became my Svengali,” she says. “He truly became my everything. But that’s very dangerous, because it’s like standing on a rug that anybody can pull out from under you at any moment.” She writes that she felt adrift and wanted a career. He was alternately too controlling and too remote.

The most uncomfortable moments come when Cannon takes LSD in a last-ditch attempt to save their marriage. Grant was a devotee of the drug and reportedly underwent 100 sessions.

Naturally, their disintegration is awful to behold, more painful than a sea urchin’s sting. After their umpteenth fight, Grant sends his lawyer to the house to tell his wife he wants a divorce. This isn’t the role anyone wants to see him in.

At the time, the public obsessed over their divorce and custody battle, and many of the ugly details are scrubbed out of this version of the story, perhaps in an attempt to make peace with the past. When it was finally over, Jennifer was only 2 years old. Her memories appear to be primarily happy ones—in her book Good Stuff, released earlier this year, Jennifer portrays Grant as a devoted father who recorded much of their time together.

After the break-up in 1968, Cannon spirals out of control, wanders out of a friend’s house late one night in her nightgown and barges in on a neighbor. Her life turns nightmarish: she’s committed to a mental hospital (just like his mother) to be weaned off of her prescriptions and heal after her breakdown.

She went on to star in Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice in 1969 with Robert Culp, Natalie Wood, and Elliott Gould. After notching a best-supporting-actress Oscar nomination for the role, Cannon told one newspaper at the time: “I don’t think anyone took me seriously when I said I wanted to be an actress—before or after I married Cary. Now maybe I’ve changed a few minds.”

They both went on to find happiness in their future relationships. (Daughter Jennifer writes fondly of Barbara, Grant's fifth wife, in her book.) Maybe it’s just the old memories dredged up in the six-year process of writing Dear Cary, but it’s hard not to sense just a touch of regret in Cannon: “Honestly, I’m able to love him more now than I ever was,” she says to me. “I think if I could have learned to love him then like I’ve learned to love now, it might have been different.”

She sees this book as less a trip down memory lane than a salve on a wound. “The reason I waited so long to write it,” she says, “was because I wanted it to be helpful and hopeful.”

And maybe it is. People are already flocking to her book signing with dog-eared pages, reciting quotes, sharing their personal stories of heartbreak. One man stood in front of her and sobbed as he said his wife had left him.

Cannon’s lessons are presented without being preachy, and touched with a sense of wonder that she managed to get through it all.

“I want to inspire people and encourage people to know that it is possible to get to that level of love that is available to everyone—the kind that can make them feel complete,” she says.

And as for that one-in-a-million movie star, maybe he really was human in the end. “I really expected him to make me happy,” she says. “After all, he was Cary Grant. I made a god out of him in my thinking, and the poor guy had things to work out like we all do.”