In a technical sense, the scope of East Lake Meadows: A Public Housing Story, a PBS documentary which debuted Tuesday night, is extremely specific. Filmmaker-spouses Sarah Burns and David McMahon follow a 30-year period from 1970, when the Atlanta Housing Authority opened a public housing project called East Lake Meadows, until 2000, when, after decades of near-criminal negligence, the city destroyed and rebuilt it from scratch. But the film also attempts to tell a larger story—about the fraught history of America’s relationship to public housing—and a timely one, as the coronavirus pandemic forces the country to confront how the government serves its most vulnerable citizens.

Executive produced by Ken Burns, the film traces the origins of East Lake Meadows back to 1934, when Atlanta officials began construction on the first public housing project in the nation: Techwood Homes. “We think of public housing as a place where low-income and mostly minority families live,” author Richard Rothstein says in the documentary. “That’s not how public housing began in this country.” Instead, Techwood was built in the shadow of the Great Depression, when millions of families—including middle- and upper-class families—lost their homes at once. The Roosevelt administration pitched public housing as a safety net for white middle-class Americans who had fallen on hard times, a stop-gap to help them ascend back to stability. Low-income or minority families were not the target demographics; their neighborhoods were bulldozed to make way for public housing.

Burns and McMahon sketch the trajectory of public housing through interviews with public officials, historians and journalists. After a while, white residents were able to use New Deal reforms to transition into homeownership, while black citizens were redlined out, given no means to accumulate wealth. “For a time, the system was working as intended,” Sarah Burns said. “It was working as a temporary place for people to get their lives together and climb out of poverty. But as it became a place where it served lower and lower income people. White people are getting all these ladders out and the people who are left behind are non-white people—in many cities, they’re African-American—and they’re low-income, the lowest incomes. That’s when we start stigmatizing it more and funding it less.”

When East Lake Meadows was built in 1970, federal and local governments had already begun to gut public housing. The earliest residents discovered quickly that the place had been constructed so shoddily it bordered on “criminal negligence,” as one attorney puts it. Sewage flooded kitchen floors; roaches and mice infested the walls; trash went uncollected for days. Through dozens of interviews with former residents, Burns and McMahon paint the picture of a place all but abandoned by local officials, left to decay around the families living inside it. During the Reagan years, most of the attention paid to housing projects like East Lake Meadows came from flagrantly racist stereotypes of welfare recipients. Archival footage flips through years of dog whistles about “superpredators” and sensationalist media coverage of gang activity and the crack epidemic.

The documentary counters those portrayals with intimate stories about the families that lived at East Lake: a mother who saved 5 dollars each week and bought her own home, a boy who watched his friend die, a resident who became the complex’s unofficial mayor. The strongest scenes come from a trove of archival footage from an old class project, when a local AV teacher sent off her grade-school students with cameras to film their home. “Where’re you gonna go,” one boy sings, as workers demolish nearby buildings, “when they tear East Lake down?”

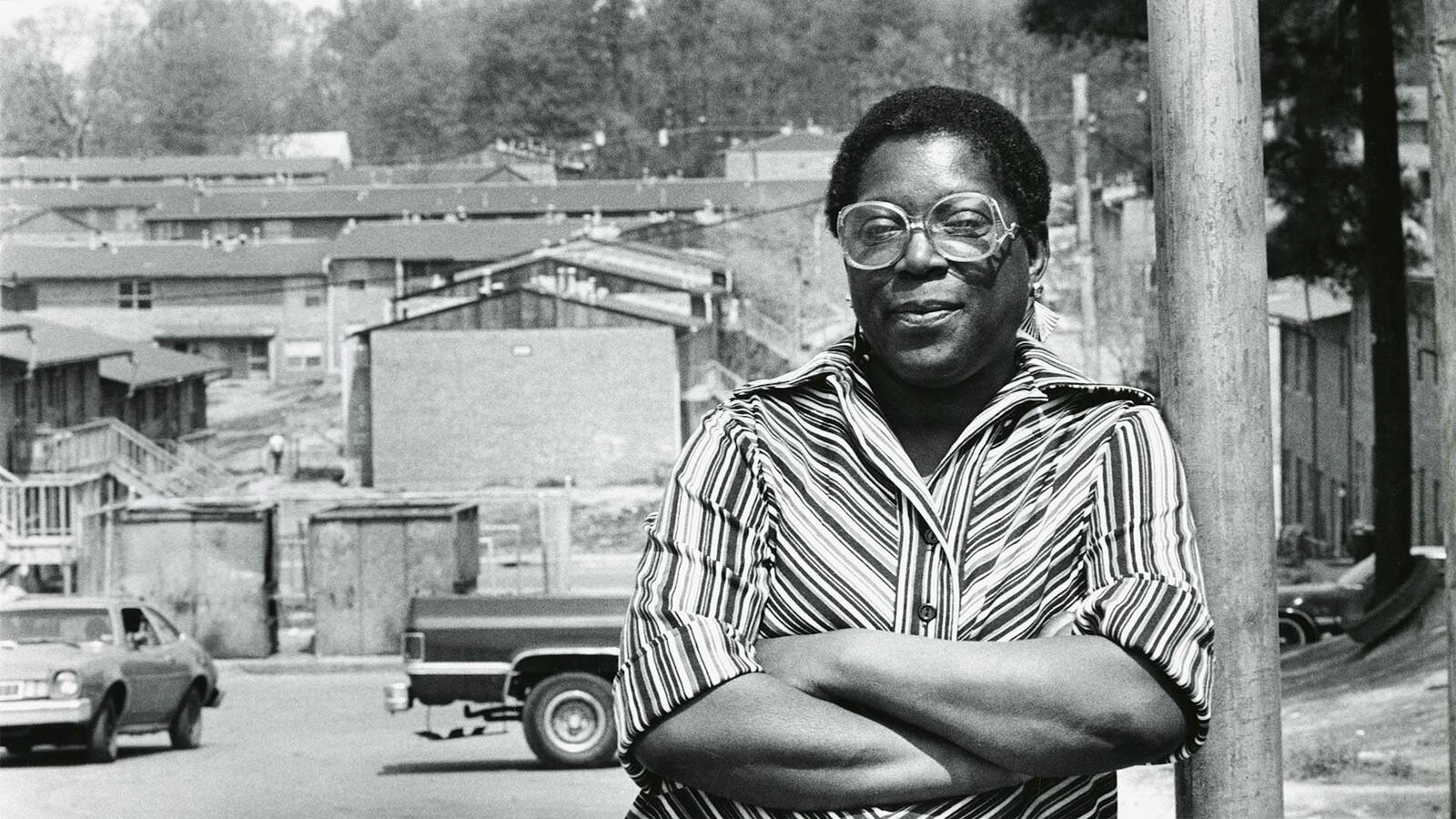

But by the mid-‘90s, the conditions at East Lake had gotten so dire nearly everyone, including residents, wanted it demolished. With a woman named Renee Glover at the helm, the Atlanta Housing Authority moved to rebuild the place as a “mixed income” community, putting most units on the private market while reserving a few for public housing. Glover consulted with East Lake residents; she even brought it a vote. The community voted overwhelming in favor of redevelopment. But as Atlanta constructed the new complex, the people it was meant to serve slipped from view.

By the time Glover unveiled “The Villages at East Lake,” most of the former residents had moved away with Section 8 vouchers or relocated to other units. Of the few that remained, only some met the income standards the new development mandated. In one of the archival school videos, some kids tour one of the new homes. It looks Levittown-ish, like someone’s baking cookies off-screen. A real estate agent asks if any of them will be moving in. She is met with silence: “No?”

As a portrait of life at East Lake Meadows, the documentary is unsparing, affectionate, and thorough, if at times sentimental. But as an interrogation of how America has failed public housing, it falls short. Burns and McMahon zero in on individuals who lived in public housing, but shy away from the people who corrupted it. They imply, for example, that Glover’s “mixed income” solution recreated the institution’s racist original sin: privileging the middle class over those most in need. And their criticism is hedged. They never confront her about it, nor do they examine the ways it might have been improved. Odder still, they overlook how housing policy has gained steam on the national stage—in Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’ and Senator Bernie Sanders’ Green New Deal for Public Housing, in Rep. Ilhan Omar’s Homes for All Act, in the growing popularity of the Homes Guarantee. But in the end, their public housing mission echoes what East Lake Meadows does best: put the people who live there at the fore.