On Oct. 15, 1888, someone put half a human kidney preserved in alcohol into an envelope with a letter taunting the police who had failed to catch the killer (or killers) of sex workers in London’s poverty-stricken East End. The letter’s return address line announced that it had come “From Hell.”

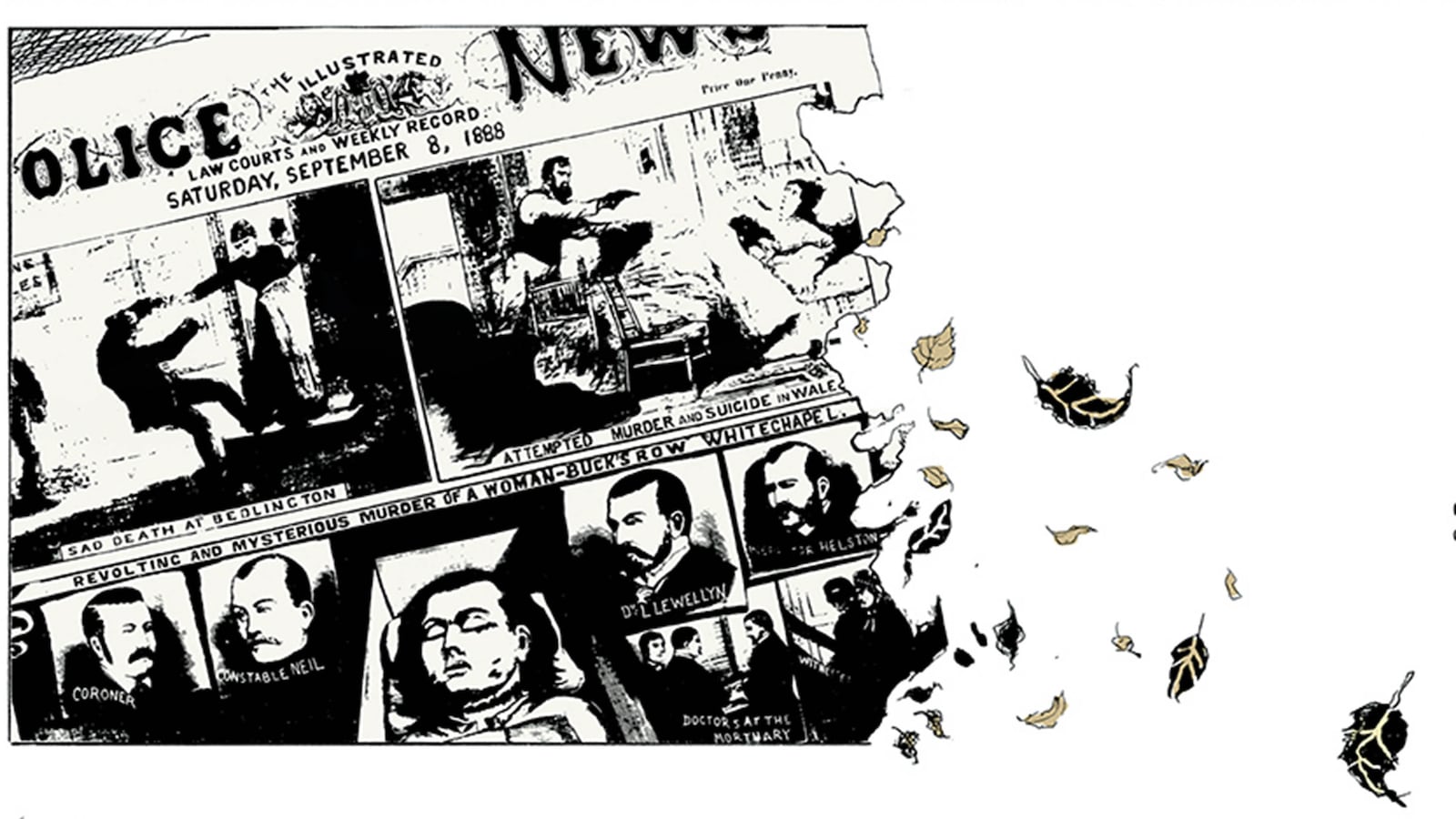

The murders were acts of profound misogyny and inhumanity, and, as such, windfalls for the periodicals of the day, especially Illustrated Police News, the weekly four-page newspaper popular among London’s largely unlettered working class for its elaborate illustrations, which covered the entire front page. The News and others wallowed in the murders, publishing images of the victims going about their daily business just before their gruesome deaths alongside drawings of their bodies and fanciful sketches of what the killer might have looked like.

And it is from those illustrations that Eddie Campbell and Alan Moore take many of their references in From Hell, the comics world’s Moby-Dick—both an encyclopedia of minutiae on its subject, and a sweeping work of immense influence and ambition in conversation with all sorts of other media. Illustrated Police News was, as Campbell once observed, “every bit as horrible as the worst sorts of comic books.”

On one notorious front page, Illustrated Police News featured four above-the-fold drawings of the murdered Annie Chapman, including a cartoon of her saying “I haven’t the money for my lodging” to her unsympathetic landlord just before she is killed—a scene Moore and Campbell recreate and embellish in From Hell.

Campbell reproduces the front page itself, as well: After Annie is killed, a distraught Liz Stride holds the paper up to show the images to Mary Kelly (both intended victims themselves). “Her insides were cut out!” Liz sobs, peeking over the top of the paper, which reads ANNIE CHAPMAN BEFORE AND AFTER DEATH, with pictures of the women’s friend alive and well on the left, with her throat cut on the right.

It’s a drawing of a lurid comic about women’s unthinkable suffering, which increases the misery of characters who will appear in a future issue, all documented in a lurid comic about women’s suffering drawn a hundred years later; a little Mandelbrot set of gendered violence that seems utterly without hope.

Many people killed Whitechapel’s sex workers, often without consequence. But in 1888, a string of five similarly gruesome and cruel murders have been credibly attributed to the single murderer we call Jack the Ripper, who may have killed as many as 11 between 1888 and 1891.

The News was far from the only publication to capitalize on this phenomenon; it was preceded in infamy by The Newgate Calendar, a monthly list of executions published by the warden of Newgate Prison and expanded upon and embroidered by other publishers, who issued chapbooks under the same name detailing the crimes for which the condemned had become famous. Notorious cannibal Sawney Bean was a popular subject, as was romantic highwayman Dick Turpin. The chapbooks were bound together like so many Batman comics (or From Hell graphic novels) and when the Ripper killed Annie Chapman on Saturday, Sept. 8, the following week’s News advertised two chapters of “A New and Thrilling Romance, entitled, THE WHITECHAPEL MURDERS; or, The Mysteries of the East End,” to be sold one for a penny, six shillings a gross. From Hell, as Campbell memorably put it, is “a penny dreadful that costs thirty-five bucks.”

From Hell begins with Prince Albert Victor (“Prince Eddy”) roaming London under an assumed name, getting a clerk at a candy store pregnant, and marrying her in secret, all without telling her who he really is. The queen’s henchmen kidnap her and put her in a madhouse, he is forcibly returned to his life of luxury, and that’s the end of it, until a few of her friends learn the truth and try to extract some money from associates of the royal family so that they can pay off a local street gang. When the royals hear of the blackmail plot, Victoria herself sends William Gull, her Physician-in-Ordinary, to do away with the women, which he agrees to do for his own reasons: He believes the stories of his mutilations will help to establish men’s dominance over women in the name of Freemasonry, and when he kills them, Gull, who has probably lost his mind during a cardiac episode early on in the book, has hallucinations of a future—our future—in which he has succeeded.

The text of much popular entertainment, especially popular entertainment for women, is the suffering of women. In From Hell, Gull himself is deliberately unreal, beyond the simple improbability of his having been the killer. On the day of the first murder, Moore and Campbell alternate between scenes from his life and scenes from hers; to emphasize the distance between them, Campbell paints Gull’s life in a gentle ink wash, and renders Polly Nichols’s grim daily routine in the stark black lines of Illustrated Police News. Gull even describes himself as “not so much man as syndrome,” and other characters seem to agree.

“What kind of men write stuff like this?” wonders Abberline, the cop chasing the Ripper, as he hopelessly ponders sheaves of false confessions filled with grotesque details. By way of answer, Moore and Campbell cut across fragments of writing as the letters’ authors compose them: A vicar just about to read his children their scripture before bed, a shifty drunk in a pub, a guy jerking off with a pen in the other hand, and a pair of teenage boys. They’re the scumbags of the analog internet at the turn of the 20th century; the ancestors of the dudes who reply “based” when a woman posts about a family tragedy on Twitter.

“The fact that one man was actually killing and disemboweling prostitutes at this time almost pales into insignificance beside the fact that lots of ostensibly normal men throughout the country were fantasizing about doing the very same thing,” Moore writes in the footnotes. What kind of men write stuff like this? All kinds, apparently.

It’s quite difficult to make an elaborate and precise work about misogyny without making a work of misogyny. If your medium of choice is true (or true-ish) crime, where detail-fetishism often reduces women to their broken bodies in the service of better understanding the men who hurt them, you have your work cut out for you yet further. But one of Alan Moore’s many laudable qualities is that if you show him a windmill, he will lower his lance and put spurs to his horse, and so he and Campbell take figure drawings of sex workers from the most lurid picture-paper of the period and animate them, giving them sympathetic flaws and charms that throw into relief the sadistic poverty in which they lived.

Campbell redrew sections of From Hell that dissatisfied him and added color for the 20th anniversary edition, which was published in September. The color, oddly, emphasizes the book’s relationship with the black-and-white drawings in Illustrated Police News: The paper itself recurs throughout the book, its crumbling edges transforming into fall leaves at the bottom of one beautiful panel; its silly picture-story about the police chief’s bloodhounds recreated on another. In a very deliberate way, From Hell is the story of these caricatures as they wander around backstage, have a smoke, try to earn their rent money, and wonder what horrors life has in store for them, before they are called onto the set to be brutally done away with for the horrified entertainment of their peers.

In an interview about his changes to the book, Campbell said he’d felt it was high time to put the women of the story on its cover; previous editions have featured Gull, and Campbell’s full-page drawing of the London skyline. But the point of the tale, the artist contended, was the victims, and so the definitive edition of From Hell features Mary Kelly, Polly Nichols, Anne Chapman, and Elizabeth Stride on the front. If you read the book carefully, it has something like a happy ending, or at least an ending that can’t be described as unremittingly bleak, but it is also about the terrible odds that its characters must survive in part because of the work reproduced and elaborated upon in its pages. Ignoring gendered violence is self-evidently wrong; Moore and Campbell make a case that depicting it sadistically is also wrong.

From Hell is incendiary, and deliberately so. It was, after all, first serialized in an anthology called Taboo. Some of its broken taboos are very English indeed: when Victoria orders the grisly Ripper murders, she is dressed in her elaborate crinoline mourning togs and rendered by Campbell in perfect respectful-woodcut style, a finger in the eye of Victoriana nostalgists. It is also offensive in more prosaic ways: Its depiction of the murders is nearly unbearable, every slash of Gull’s knife and violation of his fingers drawn with a hostile frankness. Some of this is simply the facts of the matter: Jack the Ripper horribly mutilated five women he killed. But some of it is the authors’ invention, like Gull transcending time during the final murder and having a vision of the future, in which he embraces the disemboweled corpse of his final victim and declares that they are “wed in legend” because of the killing.

Moore has written quite a few stories in which the main character steps outside of time itself and views the whole of existence as a spectator. Usually the character who can suddenly perceive the arc of history is the hero; sometimes he or she is driven mad by the experience. Almost always, it’s suggested that existence itself is a kind of comic book with extra dimensions. Gull is the protagonist of From Hell, the guy in the 4D god-seat, and an evil murderer written by Moore to be the embodiment of misogyny; a kind of Satanic figure who is working constantly to subjugate women. From Hell, the four-point-three-pound physical object, is a metaphor for hopeless, misogynistic reality itself. It is a profoundly, and deliberately, disturbing book.

Like Illustrated Police News and the penny dreadfuls advertised in its pages, comics are a cheap medium, made to be read and piled somewhere or handed down to another kid in the neighborhood. The special effects budget is in gallons of ink, as are the casting limitations, and while the appeal of the form to people with limited print literacy is the subject of many fabulous jokes, it is also a quality that in the past allowed a breadth of readership that prose fiction didn’t have, or seem to want. Comics can be a lingua franca across classes, just like the news, and while their domination by AT&T (which owns DC) and the Disney corporation (which owns Marvel) has made aspects of the art pretty grim, it remains an unparalleled way to make your point. Write a mean column about a political opponent and your editor might get an angry phone call; draw an unflattering picture of her and she will try to have your work censored. They are a good way to make a moral argument as indecorously as possible.

That’s what makes From Hell a masterpiece: It uses the language and grammar of persistent, centuries-long misogyny to investigate and criticize itself; to enter the discourse of tabloid media and taint it so that it no longer lands quite the same way. It’s hard to read a front-page crime story in the same way after seeing Campbell render 19th-century mugshots and crime-scene photographs full of rich, immutable life, whether or not some monster has emptied that life all over the cobblestone, or the page.