Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak is confident, he says, that the United States has plans for surgical strikes against Iran as a last-ditch measure if Tehran refuses to stop its development of a nuclear-weapons capability.

In a televised interview at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, on Thursday, Christopher Dickey of Newsweek and The Daily Beast noted the American administration’s reluctance to involve itself in another Muslim world war and asked if there were any way Israel could go to war with Iran that did not drag in the United States.

“I don’t see it as a binary kind of situation: either they [the Iranians] turn nuclear or we have a fully fledged war the size of the Iraqi war or even the war in Afghanistan,” said Barak. “What we basically say is that if worse comes to worst, there should be a readiness and an ability to launch a surgical operation that will delay them by a significant time frame and probably convince them that it won’t work because the world is determined to block them.”

“We of course prefer that diplomacy will do,” said Barak, “We of course prefer that some morning we wake up and see that the Arab Spring was translated into Farsi and jumped over the Gulf to the streets of Tehran, but you cannot build a plan on it. And we should be able to do it.” That is, stage a surgical series of strikes.

Barak said he used to mock his American friends in the past. “I used to tell them, you know, when we are talking about surgical operations we think of a scalpel, you think of a chisel with a 10-pound hammer.” But that’s not the case with the Obama administration, Barak said. Under orders from the White House, he noted, “the Pentagon prepared quite sophisticated, fine, extremely fine, scalpels. So it is not an issue of a major war or a failure to block Iran. You could under a certain situation, if worse comes to worst, end up with a surgical operation.”

The Obama administration has said flatly it will not allow Iran to become a nuclear-weapons power, but diplomatic progress toward neutralizing the threat has been extremely slow, even as Iran’s nuclear technology and supply of potential materials for weapons continues to grow.

Barak said much more draconian sanctions against Iran need to be applied, including a kind of “quarantine” on imports and exports, but he noted that getting such measures past the Russians and Chinese at the United Nations would be very difficult. Indeed, he said he does not expect the Iranians will bend.

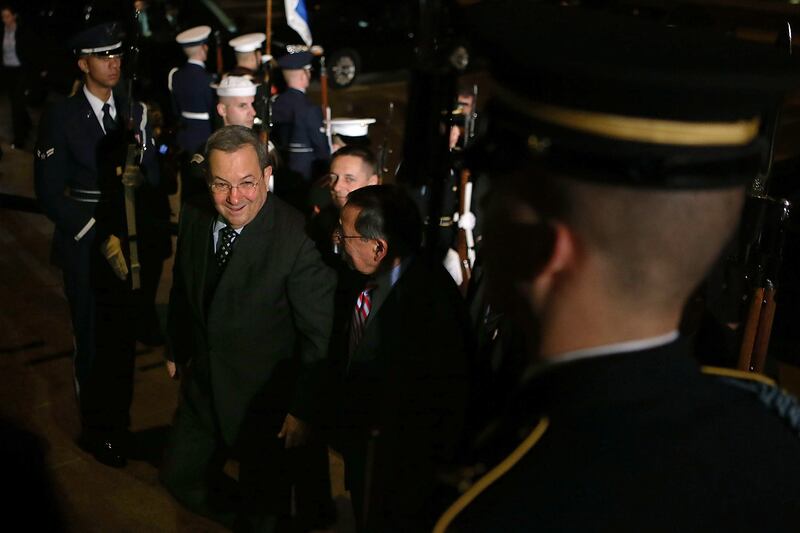

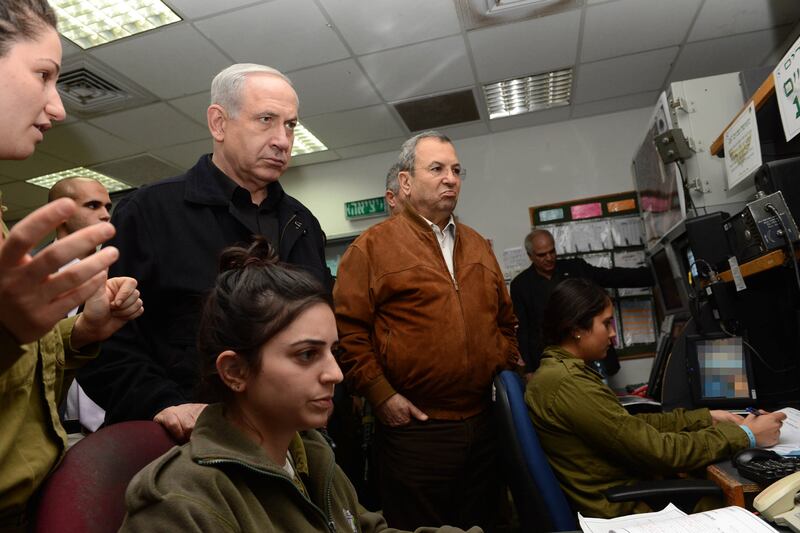

Barak, who previously served as prime minister, still holds the defense and deputy prime minister portfolios in the lame-duck Israeli government. Elections earlier this week surprised most analysts—and Barak, he said—by making a new center-left party led by TV anchor Yair Lapid the second-largest in the Knesset, and negotiations for a new cabinet led by a weakened Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu are now underway. But Barak, for the moment, has ruled himself out of the action and plans to retire from politics, at least for several years. “In Israel it’s never too late to come back,” he half-joked. “In five years’ time, I will still be 15 years younger than [Israeli President] Shimon Peres, and he will be only 95.”

In the wide-ranging interview at the Davos summit, Barak said the rise of Lapid’s Yesh Atid Party was a reflection of the weariness of the Israeli people with a government that has given too many exemptions to religious interests and has moved too slowly, if at all, in the effort to make peace with the Palestinians. There is a powerful need among many Israelis, said Barak, “to see something new or fresh” in politics.

Barak, who tried to strike a grand bargain with the Palestinians in 2000 and failed, nonetheless reiterated his strong support for a two-state solution as the only real way to meet the aspirations of both the Israeli and Palestinian people.

Commenting on what he has read about a controversial new documentary that features interviews with six former heads of the Israeli domestic intelligence and apparatus, the Shin Bet, and is fiercely critical of the Netanyahu government, Barak expressed some sympathy for the views of his former colleagues. They wanted to tell the Israeli public, he said, that “there is a price” for continuing to “reign” over the Palestinians.

Asked how Israeli defense plans have changed because of developments in the Arab world right on Israel’s frontiers—the rise of jihadists, the civil war in Syria, the election of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt—Barak said, “It’s like trying to make a priority between the plague and cholera.” And in an interesting twist, he suggested that the failure of the international community to stop the slaughter in Syria could be a lesson to Israel that despite all assurances that the world will act when a certain threshold of atrocity is crossed, sometimes that just doesn’t happen.