Reading Elena Ferrante’s novel The Lost Daughter for the first time, Maggie Gyllenhaal, who would go on to adapt and direct it in a critically acclaimed, Oscar-nominated film, said that Ferrante “was saying things out loud that I knew to be true, but I had never heard said out loud. And I found that both disturbing and comforting, and I thought, in fact more than that, it was kind of like… a really exciting shock.”

Gyllenhaal’s description is apt. We know certain things to be true. But when they are spoken out loud—or, taken a step further, when they are written down, they draw a new, feverish kind of power.

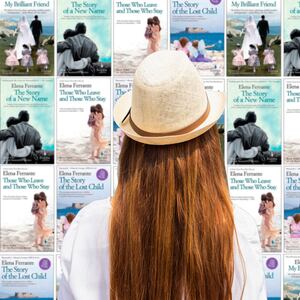

Ferrante, the Italian author of nine novels, most translated into English by Ann Goldstein, may publish her work pseudonymously, but the message of her writing is clear: to write the truth of women’s lives, even when it comes to ugly feelings on friendship, marriage, and most damningly, motherhood.

The essays in her new collection, In the Margins, were meant to be delivered as lectures. There are only four in this slim volume by Europa Editions, but as with all of Ferrante’s work, they pack a punch. Reading this book is like reading the Rosetta Stone of women’s writing. “The lowly, abject woman,” Ferrante writes, “having her say.”

In her early novels, Ferrante writes, her protagonists “were writing autobiographies, diaries, confessions, driven by hidden wounds.” After reading Gertrude Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, in which Stein writes about herself through her lover Alice, Ferrante realized the need for “a necessary other,” a “perimeter of freedom within which I could display, without self-censure, capacity and incapacity, virtues and flaws, wounds that don’t heal and sutures, obscure feelings and emotions. Not only that: it also seemed to me that I could produce that double writing I was talking about.”

In other words, Lila and Lenù, the two protagonists of the Neapolitan Quartet, are not only writing themselves, they are writing each other and everyone who surrounds them. Inspired again by Stein’s book, in which Stein (as Alice) describes herself as a genius alongside Hemingway and Picasso, Ferrante delights in Stein’s audacity. Like Gyllenhaal’s reaction to The Lost Daughter, in a “really exciting shock,” Ferrante changes the title of her magnum opus. “After having for a certain period called my draft The Necessary Friend, I began calling it My Brilliant Friend.”

To establish the female voice as a voice of truth is the assignment Ferrante gives herself. Citing Emily Dickinson’s poem “History & I,” it is that conjunction that gives the idea its power. “Patrimony is essentially male and by its nature doesn’t provide true female sentences,” she writes. Dickinson, who places herself right alongside History in her poem, is a jumping off point. What do true female sentences sound like? “It felt like I’d been trying not to explode, and then I exploded,” Leda, played by Olivia Colman in the adaptation of The Lost Daughter, describes her choices. “How did it feel?” Nina asks, surprised. “It felt amazing,” she says, the tears jumping from her eyes.

As to whether or not she has succeeded in writing the truth is unclear to Ferrante herself. “We have to accept that no word is truly ours,” she writes. “But I’ve never stopped believing in the importance of the writing we’ve inherited, which the ‘I’ who writes, like it or not, is made of.”

Never have the constraints of that “I” been clearer for women and the female writer than, perhaps, in the work of Ferrante. But that feeling of entrapment, “I’m suffocating,” as Leda says to her husband in The Lost Daughter, is what drives Ferrante to keep writing. “The challenge, I thought and think, is to learn to use with freedom the cage we’re shut up in. It’s a painful contradiction: how can one use a cage with freedom, whether it’s a solid literary genre or established expressive habits or even the language itself, dialect?”

Ferrante’s determination to remain anonymous despite the many attempts to get her to reveal herself publicly and publish her work under her given name has undoubtedly contributed to the curiosity around her work. As a result, In the Margins feels like a Wizard of Oz lifting the emerald curtain. But instead of being revealed as a small, impotent man, Ferrante reveals herself as a purposeful writer, each book a step towards a marked goal, a journey to a kingdom of truth. “I now think that if literature written by women wants to have its own writing of truth,” Ferrante calls to the reader, “the work of each of us is needed.”

Regardless of how one might feel about the experience of reading Ferrante’s work, in particular the Neapolitan Quartet, which has all the foundational heft of the Holy Bible, there are few, in fact, practically no other writers with such a scaldingly clear idea of what they’re writing, and why. The title of this collection comes from Ferrante’s memories of writing in her childhood notebooks. Being “in the margins” has a negative connotation—of being underrecognized and/or miscategorized. But for Ferrante, writing from the margins gives her the necessary space for truth, and yes, brilliance.