Elias Khoury is the author of 16 books, including 11 novels, and is one of the leading Arab writers of his generation and an enduring influence in the political culture of his native Lebanon. For more than a decade he's been a Global Distinguished Professor at NYU, teaching there each spring, while spending the rest of the year in Beirut. But in the bustle of New York, it's easy for him to go unrecognized, and despite his reputation abroad, he hasn't established much of a footprint in the United States, where the independent press Archipelago Books has brought out four of his novels in gorgeous, deckle-edged editions.

I met with Khoury this spring, a few days before he was to fly to Beirut. We talked about As Though She Were Sleeping, his latest novel to be translated into English, his varied life as a militant, writer, and political activist, and the Arab Spring. After speaking with Khoury and studying his work, it's clear to me that, while he's a veteran of an earlier generation's political struggles, particularly the Palestinian liberation, he remains a vital and perceptive on today's Middle East. Still an active campaigner for liberal causes in Lebanon, his lively and challenging novels position him in the tradition of those like the Syrian poet Adonis, as a major cultural figure whose combination of literary achievement and political independence give him a unique authority. At the same time, like Adonis, he's both drawn heavily on the Arab literary tradition and broken traditional rules about language, subject matter, and structure, remixing it into a literature all his own.

When we spoke, the situation in Syria, which has since only gotten more dire, particularly concerned Khoury. He would love to see the Syrian people to throw off the yoke of dictatorship but was also worried about violence spilling over into neighboring Lebanon.

“It's as if what's going on in Syria can happen at any moment in Lebanon,” he said, “so everybody's afraid.”

Khoury has a sister who lives in Damascus—she's married to a Syrian—and he's concerned about her. They speak regularly on Skype, and when we met she was safe. But in addition to fighting brutal battles against rebels who have growing popular support, the Assad regime has committed massacres that recall the pre-“surge” bloodshed in Iraq, when the country was fractured by sectarian fighting. Syria could fall prey to the kind of vicious sectarian conflict that Khoury has spent a career opposing in Lebanon.

From his early days as a Christian member of a largely Muslim organization (the Lebanese National Movement), Khoury has resisted factionalism, but the dynamics of Lebanese politics—an ethnically divided parliament, the state-within-a-state of Hezbollah, and the frequent meddling of neighboring nations—don't leave much room for independent actors.

“We intellectuals, leftists, seculars, we try to make our solidarity with the Syrian people outside this dichotomy. But inside this dichotomy it'll be meaningless, because you're not making any solidarity. You are Sunni with the Sunnis of Syria, against the Shiites of Syria, which doesn't interest us at all. We are against the whole discourse.”

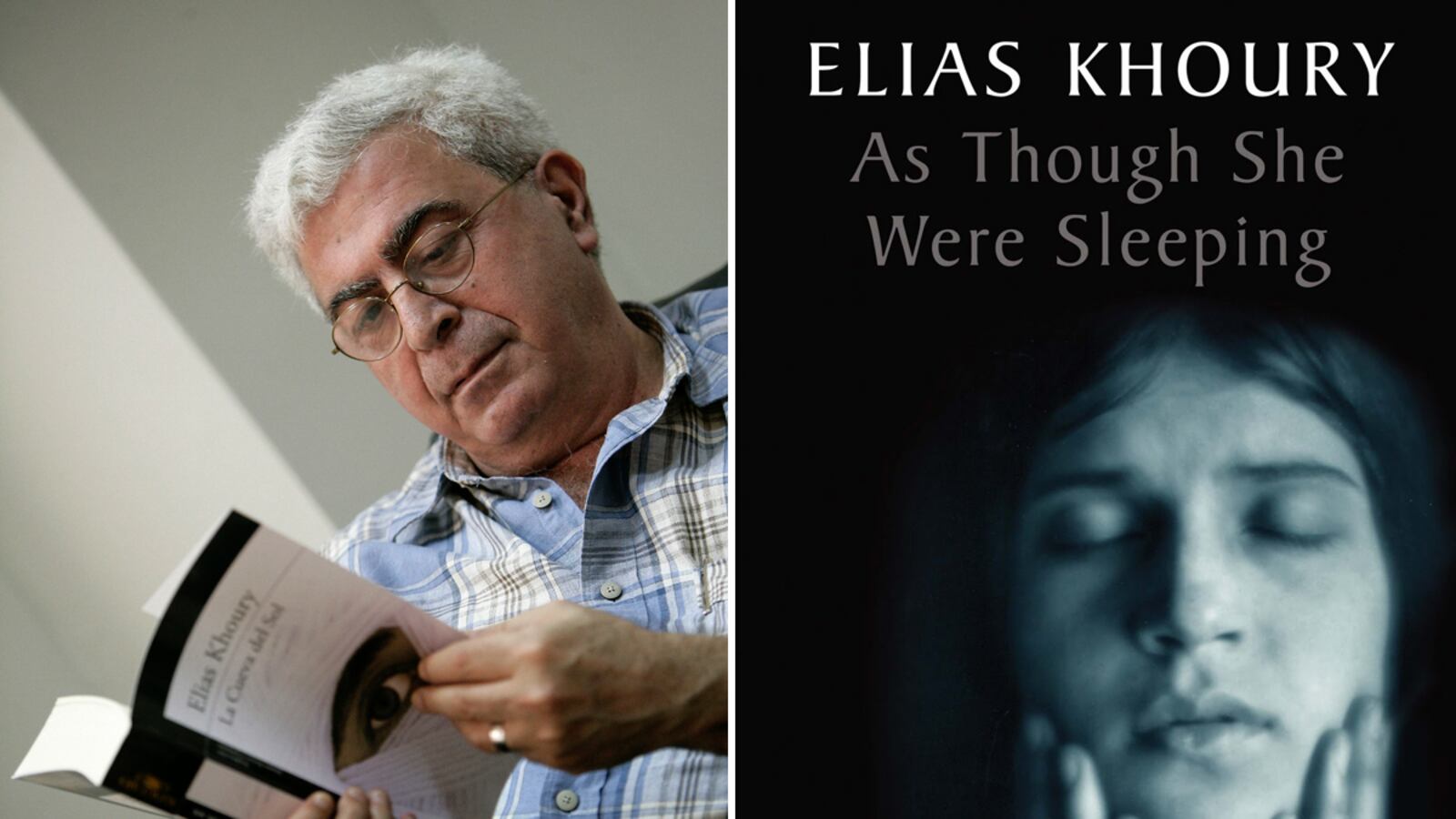

In person, Khoury is genial and a fine conversationalist, speaking English gilded with a pronounced Arabic accent. He wears glasses and is noticeably cross-eyed (he was injured during the Lebanese Civil War and temporarily blinded). His hair is a thinning silver brillo pad, and his belly juts forward from beneath his suit jacket.

Born in 1948, Khoury grew up in an Oriental Orthodox Christian family in the east Beirut neighborhood of Ashrafiyyeh, or “Little Mountain” (it would also serve as the title of one of his early novels). The Khoury family was traditional and middle class; Elias' father eventually became a manager for Mobil. Elias read poetry with his grandmother, and while he's never been religious, he loves religious texts. He's memorized parts of the Koran and considers the Book of Job “a literary masterpiece.”

In 1967, a time in which liberation theology was ascendant in Latin America and anti-colonial movements and the Six-Days War had helped to radicalize a generation of leftists, Khoury joined Fatah, beginning his time as a militant—or at least, that's the term he's used to describe himself. But, as Khoury argues, it doesn't fully capture his younger self:

“After the defeat of 1967, the flow of new Palestinian refugees was catastrophic. I thought at that time our moral engagement released us to fight back. For me it's part of my history. I'm proud of it. Maybe I would not do it now. But at that moment, it was a necessity. We were in the Vietnam War, we were in Che Guevara, we were in a world where there was this central idea that we have to change the world, and we have to do all our best to change it. So at that time, for me it was evident. I don't think it was heroism. It was part of being what you are. If you identified with the Palestinians, you had to do it. There was no other way.”

Khoury's passions have never waned, even if his means have changed. He still believes strongly in democracy, secularism, Palestinian self-identification, and the potential of the Left. But he's unlikely to take up arms, as he briefly did during the Lebanese Civil War, which lasted, in one form or another, from 1975 until 1990.

“Actually I have a big question mark about using arms after all we went through,” Khoury tells me.

As Though She Were Sleeping reflects a skeptical attitude towards combat. A character named Mansour doesn't want to rejoin his family in Jaffa, where he would have to fight against Jewish rebels. The novel also presents a call to pacific resistance that speaks of lessons drawn from the hardships of the last few decades: “you all—you Palestinians—will know that struggle yields victory only through the word, for it is stronger than weapons.”

Despite his sympathies, Khoury has always been wary of politics, and he's spoken ruefully of the times he's allowed himself to become involved in political organizations. He “was stupid enough to accept a position with the executive committee” of a group pushing for Syria to withdraw from Lebanon. He resigned 8 months later—the implication being that the fault lay with the organization, not the cause.

But Khoury's career has brought him into contact with a raft of prominent Lebanese, Palestinian, and Arab politicians and politically active intellectuals. If not a politician himself, he's positioned himself in their orbit. He started a journal with Mahmoud Darwish, the great Palestinian poet. For a time he wrote criticism for Mawaqif, a publication founded by the Syrian poet (and perennial Nobel also-ran) Adonis. He was friends with Samir Kassir, a Lebanese professor and journalist assassinated, possibly by the Syrian security services, in 2005. Khoury was colleagues with Kassir at An-Nahar—Khoury edited the newspaper's cultural section—and Kassir's office was left untouched after his death.

“For me, politics was defending the major values of democracy, of social justice, and so on,” Khoury says. “But I was never part of any political machine in the real sense.”

There is a congenital contrarianism in Khoury. Early in the Civil War, when most Lebanese Christians aligned themselves with right-wing militias, he joined the Lebanese National Movement, whose leftist beliefs matched his own, but he took that same movement to task in his 1981 novel White Masks. He's frequently criticized Hezbollah but believes it was defending Lebanon from Israeli aggression in the conflict between the two sides in the summer of 2006. At the time, Khoury was in Beirut, where he helped to open schools for refugees from the country's south. Later he toured the south and reported on the devastation he witnessed there.

A closer analogue for Khoury's role may be Edward Said, the late Palestinian scholar known for his political activism and acerbic critiques of western Orientalism. Khoury knew Said well, and Said wrote an introduction to an edition of Little Mountain. In it, he speaks of Khoury glowingly, as a pivotal force in Arab literature after Naguib Mahfouz, the Nobel Prize Winner who essentially brought the novel form into modern Arabic literature.

Said calls Khoury “brilliant,” writing that he is also “a mass of paradoxes.” The tone is of one foundational figure proudly acknowledging another: “At great personal risk... Khoury has forged (in the Joycean sense) a national and novel, unconventional, fundamentally postmodern literary career.”

And it's true that Khoury, who writes largely in a colloquial Arabic, has been a major innovator both stylistically and topically. His work is often characterized by a circuitous, stream-of-consciousness-like approach, and an emphasis on what he calls the “tension between time and timeless[ness].” He once told a journalist from The Guardian that “in my fiction, you're not sure if things really happened, only that they're narrated.”

His expansive novel Gate of the Sun, considered by many to be his most important work, is the rare Arab novel to directly confront the Nakba (“the disaster”), the 1948 war that resulted in the founding of Israel and the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees. Published in English translation in 2005, the novel was widely praised, and though Khoury is Lebanese, it is perhaps not inappropriate for him to refer to the book as “the Palestinian novel,” as he did in our interview. (Khoury is now working on a novel that he calls “a continuation of The Gate of the Sun.”)

His iconoclasm extends to frank depictions of sex and sulfurous critiques of Arab governments. But Khoury resists the notion that he's breaking taboos for their own sake. When someone at his book-release party asked how his depictions of sex are received by Arabic-language readers, Khoury was insouciant.

“They love it. Arabs love sexuality like everyone in the world—what do you think?”

Khoury claimed that some Arab writers deliberately push sexual taboos. “And then they run to the west and cry that they're persecuted,” he said. “I don't push taboos. I don't care.”

There's a consciousness of the wider Arab world in Khoury and his work, but he's not a pan-Arabist per se. He celebrates the diversity of the Middle East and North Africa and the way that Arabic has been both a unifying cultural force and led to the formation of unique dialects.

“I believe that I am an Arab first of all,” he said, “and that Arabic is a beautiful language, one of the greatest languages, that I want to defend.”

And though he's a strident critic of Israel, and Israeli treatment of Palestinians, he's thoughtful when speaking about Muslim-Jewish relations, often referring to Jews as “our cousins.” He supported, for example, the translation of his work into Hebrew. His time in New York has allowed him to develop some close friends friendships with Israelis and to pick up some Hebrew. (He also speaks French, having studied in Paris, where he knew Julio Cortazar.)

In New York, he draws a small crowd, but it's a fervently devoted one. On a balmy spring night at Alwan for the Arts, a small cultural space in downtown Manhattan, a few dozen admirers gathered to celebrate the release of the English edition of As Though She Were Sleeping.

“His writings remain a compass for so many of us,” said Simon Antoon, the Iraqi author (and fellow NYU professor) who introduced the featured guest. “Khoury has been setting the bar for experimentation,” particularly in his willingness “to unmake and destabilize narratives from within.”

After a few minutes in this vein, Khoury leaned in to his microphone and offered, “I would like to meet this man he's speaking about.”

The crowd laughed appreciatively and soon Khoury was off, speaking passionately about the protagonist of As Though She Were Sleeping, a woman named Milia who spends as much time awake as she does immersed in vivid dreams that are alternately phantasmagorical and fantastically lifelike. The novel takes place mostly early in Milia's marriage to a gregarious but overmatched man named Mansour. The action is centered in Beirut and Nazareth in 1946 and 1947, but the narrative also embarks on abrupt flights into the future and the past, either real or dreamed. The distinction is rarely clear; indeed, the novel's chief quality is a continual flux of action, memory, and dream, all of which is equally “real”—or unreal, as the case may be. The novel's not atmospheric so much as it is an atmosphere—a swirling amalgam of Milia's dreams, Biblical prophecy, and ancient Syriac parables. The same stories—of a fervently religious nun who has a totalitarian hold on Milia's mother, of an exiled mad monk, of a boy who accidentally hangs himself in a bell-tower, of an absconded lover—are told repeatedly but almost never the same way twice. Each telling brings new details or perspective, making the book both repetitive and prismatic.

Although he had finished the novel years earlier, Khoury spoke of Milia with such fondness and immediate recall that it seemed as if she were someone in the other room.

“I had the fortune to love her,” he said. “She taught me a lot about life and about literature.”

A woman sitting next to me leaned over and asked if he was speaking about someone real.

No, I told her. It only seemed that way.