Over the course of three extensive interviews, Sheldon Stephens maintained that he had no intention of going public when he approached Sesame Workshop, the nonprofit organization that produces Sesame Street, about his relationship with Clash in June.

(When The Daily Beast first contacted Stephens, a woman who said she handled his publicity asked if he would be compensated for speaking out. After he learned he would not, Stephens agreed to be interviewed anyway, because he wanted to set the record straight “that I am not a bad person.”)

For about a year prior to e-mailing the organization, Stephens—a 24-year-old from Harrisburg, Pa.—said his mind had been going to “dark places” remembering events that he had been advised by a relative to suppress. He said he’d sometimes visit his toddler nieces to relax, but instead he’d be bombarded with images of Elmo—on the TV, in Sesame Street toys and on DVDs.

ADVERTISEMENT

“It was, like, an overwhelming thing,” said Stephens, who is finishing a bachelor’s degree at Harrisburg University of Science & Technology. “It started to become, like, wow, maybe something is telling me to do something. If I turned on the TV, if I opened a book or a magazine, or even Netflix, there it was. And it just wouldn’t shut up in my head.” (He had two jobs until the scandal broke; he lost them.)

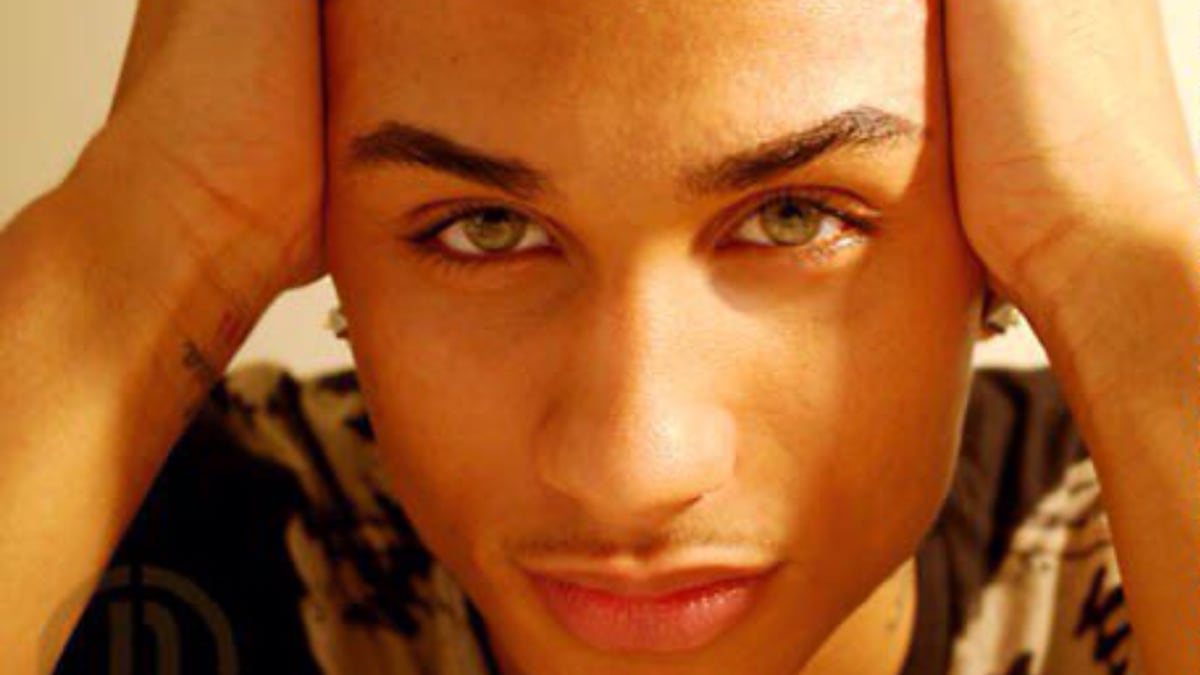

Stephens’s narrative goes like this: When he was 16, he met Clash at an entertainment-industry charity mixer. The handsome green-eyed teenager, who had been modeling and acting since he was a boy in Florida, struck up a conversation with Clash, who would have been 43 or 44 at the time. Clash offered to stay in touch and introduce him to prominent industry representatives. Clash didn’t tell him that he worked for Sesame Street, but during their first phone conversation shortly afterward, he told Stephens to look him up on Google to find out who he was.

Over a period of six or seven months, Stephens said, he and Clash communicated by telephone, email, and video chats. Clash asked him for photographs and said he would send them to his contacts.

“Because I grew up with six brothers and sisters, I grew up a little faster,” Stephens said. “I was more independent. I started working when I was 14. I just knew that in life you have to know certain people and you have to put yourself out there to elevate yourself and open up other doors. For me, I was thinking, This could be a great thing. This could be the doorway to possibly making my dreams kind of come true.”

But no meetings or job opportunities ever materialized. Instead, Stephens said, he and Clash became friends. Then, gradually, “it got more to Kevin insinuating sexual things.” At the time, Stephens said, he was a virgin and had only dated girls.

That all changed the first time Clash invited Stephens to his Upper West Side apartment in Manhattan. According to Stephens, Clash, his driver and Stephens all used crystal meth and engaged in foreplay. But Stephens said he only had sexual intercourse with Clash and never saw the driver again.

“I was still finding myself,” Stephens recalled. “I knew it was wrong, but I also felt like I was growing up and they were very smart about it. I can’t even really explain it. I always felt it was creepy. I always felt it was wrong. But I stayed. I wasn’t raped. I just told myself it was OK so I would not be constantly depressed or confused.”

Stephens said his sexual relationship with Clash continued, but that they would only see each other when Stephens could find the time to visit Manhattan on weekends. When they got together, he said, they would have sex and sometimes use poppers. They were also bonding emotionally.

“It started to develop that way,” Stephens said. “Now I’m into men all of a sudden. And I tried to make it right in my head. I was trying to justify it. He told me he loved me. Slowly, as time passed, I started to believe it. I thought, Maybe this is really something. Why else would he say it?”

After Stephens graduated from high school, he moved to New York City, but he and Clash saw less of each other. Stephens said he went through a “rebellious” stage, partying and getting into some trouble, until he decided to confide in his grandmother, a devout Jehovah’s Witness.

“She’s been in the church for, like, 50 years, and they don’t go to court, they don’t get involved in politics,” he said. “So it wasn’t like she wanted to call the cops. She told me sometimes things happen in life and you just have to move on … She opened up this new chapter for me.”

Stephens left New York City when he was 20 to begin college in Harrisburg, but he traveled often to the city for work. He also maintained a sporadic sexual relationship with Clash, he said, until “he told me his [personal representatives] told him not to have interaction with me anymore. I think his people saw certain fluctuations and patterns. Maybe him spending money on all this crazy stuff.”

Stephens, who was 21 at the time, wrote Clash letters.

“When he told me we couldn’t talk anymore, I wrote him that instead of helping me out, he focused on stealing my manhood. He never replied. I think he thought he had me in a safe place.”

But as Stephens continued to network in New York City show-business circles, he met other people who knew that he had been involved with Clash. From them, he said, he learned he was not the only teenager linked to Clash. He never met any of the others or knew their identities, but he said he often thought of them, especially when he played with his nieces, surrounded by Sesame Street merchandise.

Last summer, Stephens decided he could not stay silent any longer. In June he emailed Sesame Workshop to tell them what he knew about Clash. “It was information they needed to know, because he was hanging out with a lot of young boys and that’s crazy. And I was literally going crazy inside my head because I couldn’t tell anyone. I knew what was behind that thing, Elmo.”

Stephens said he followed his grandmother’s advice and didn’t go to the police. “It would bring my brain down even more to call the cops,” he said. “I know it doesn’t make sense, but I did have a little respect for [Clash]. I knew he had a daughter. I knew that he pays for his family’s mortgages, and he has a lot of responsibility. I wasn’t trying to bring him down. A lot of people tell me now that I’m the victim, that I shouldn’t be worried about those things. But I didn’t really understand that until now. I just wanted them to know because he works with children.”

Stephens said he also told Sesame Workshop that he didn’t want any money and that he wasn’t looking to have Clash fired.

In multiple statements last month, Sesame Workshop acknowledged receiving the allegation and conducting an internal investigation, as well as commissioning one by an outside firm. Based on those investigations as well as “Kevin’s vehement denial, we found no evidence of an underage relationship,” a statement on Nov. 27 said.

A source close to the investigation told The Daily Beast that the organization responded “seriously and without delay” to Stephens’s e-mail.

“He was repeatedly asked to present his allegation with any supporting documentation he might have,” the source said. “He did not do so. He did not present any information about any other persons making similar allegations, nor had any such information otherwise been presented to Sesame.”

According to Stephens, after Sesame Workshop received his email, the company bought him a train ticket so officials could meet with him in person in New York City. When he did not take the train, the company’s general counsel, Myung Kang-Huneke, traveled to Harrisburg to meet him.

“She asked how they could make it go away, and if an apology from Kevin would be enough,” he said. “But he never came with that apology. Nobody ever brought it up again.”

A second meeting in Harrisburg was arranged in July. This time, Stephens said, an outside attorney, Kathleen McKenna, of Proskauer, accompanied Kang-Huneke and things quickly got tense. The lawyers accused Stephens of being an “extortionist” and handed him his own criminal background report, he said.

“I told them if I knew the meeting was going to be like this, I would have brought an attorney or my parents,” Stephens said. “I told them I just want Kevin to know he needs to stop doing what he is doing. But after that, I felt my life was being threatened and I needed to lawyer up to protect myself.”

McKenna referred a request for comment to representatives for Sesame Workshop, who declined to be interviewed. But the source close to the Sesame Workshop investigation told The Daily Beast that Stephens “was not accused of engaging in extortion” but he did, in fact, “suggest as resolution ‘substantial monetary payment.’”

Stephens denies this version of events. “That’s definitely not true,” he said. “I wouldn’t have gone to a major company like that without any legal representation demanding money. That’s not what I did and that’s definitely not what I said.”

After the second meeting, Stephens hired an attorney, Ben Andreozzi, whose firm specializes in sexual-abuse cases, including one of Jerry Sandusky’s child-rape victims. Andreozzi asked Stephens to take a lie-detector test and advised him to sue Clash, even though Stephens said he told him from the start he was not interested in legal action. Andreozzi declined to be interviewed for this article.

On Nov. 12, TMZ broke the story that Clash had taken a leave of absence to deal with the allegations. At the time, Stephens’s identity was not public, and he vehemently denies he was the leak. Clash issued a statement that day which said: “I had a relationship with [the accuser]. It was between two consenting adults and I am deeply saddened that he is trying to make it into something it was not.”

But behind the scenes, Stephens said, there was panic. Andreozzi went to New York City alone to meet with lawyers for Sesame Workshop and Clash. He called Stephens several times during that trip, in an effort to draw up a settlement agreement. Stephens said Andreozzi told him that if there hadn’t been a leak, he probably would have been able to get close to $1 million. But because of the press reports, the lawyer told him, negotiations began at $250,000 and went down from there, Stephens said.

“It wasn’t about the money initially,” Stephens said. “But they put the money on the table and I’m going to take it. I’m going to finish school, my mom needs help paying bills, my niece is about to go into pre-school. I’m taking the money to better other people’s lives and my own.”

On Nov. 13, Andreozzi issued a statement saying that Stephens, whose identity was still unknown, “wants it to be known that his sexual relationship with Mr. Clash was an adult consensual relationship.”

Under the final settlement, which Stephens said he signed on Nov. 13, Clash was to pay him $85,000 within 10 business days and another $40,000 within 12 months. For his part, Stephens says he was supposed to say publicly that his relationship with Clash began when he was 18.

“I told my lawyer that I didn’t feel right with this because I’d be lying, and he told me it was the only option we have because the information got leaked,” Stephens said. “They wanted to kill the media stories. He told me not to talk to my parents or anyone. I was just listening to him. This is my lawyer. Because I was mentally confused and everything was happening so fast, I went into the contract. I didn’t want it to go public. I didn’t want to go to court. I didn’t want any of this to happen. I feel like the devil really got a hold of the whole situation. When we signed the contract, my name was private.”

That didn’t last long. On Nov. 14, The Smoking Gun website disclosed Stephens’s identity and published a report about his alleged run-in with the law, including a Sept. 2009 incident at Harrisburg International Airport, where police stopped Stephens after he exited a flight from Los Angeles wearing what they believed to be $250,000 in stolen diamond jewelry. The charges were dismissed two weeks later, and Stephens refers to the incident as a “misunderstanding.” But he immediately lost both of his campus jobs in the wake of the revelations.

When contacted by phone, Darian Pollard, founder of DP Music Entertainment Group, who had reported the stolen jewels to Beverly Hills police, said he had not heard of Stephens. He later referred all inquiries to his attorney, Gloria Allred. Stephens said he and Pollard remain friends and have traveled together since.

In the days after he signed the settlement, Stephens was interviewed by The Insider and 360Magazine on camera and stuck to the new story that he was 18 when he and Clash embarked on their relationship.

On Nov. 17, TMZ reported that Stephens signed the settlement, but “he continues to insist Clash had sex with him when he was a minor and was pressured into signing the settlement.” TMZ did not reveal its source for that information and Stephens maintains that he was not the source of that leak either. TMZ did not respond to a request for comment for this article.

When asked why he said he was 18 then and now says he was 16, Stephens said, “I did lie on film because of what my lawyer advised me and what the contract had said,” Stephens said. “I didn’t know other people would be influenced by me to come forward. If I had known that, I would have never signed the contract. I would have just been a role model for people and a voice for people. Honestly, I feel like I was set up.”

Stephens said he still hasn’t received any money from Clash, although the 10-day mark for the initial settlement payment has passed. Stephens’ lawyer, Ben Andreozzi, told him he received a letter last week claiming that Stephens had breached the settlement because of the reports that he had taken back his recantation, but Stephens said he and Andreozzi have not spoken since.

Out of the three men that have come forward, Stephens is the only one who knew who Clash was from the beginning of their relationship. When they met, Clash had just divorced and he shared some of his personal pain with Stephens.

“We’d be hanging out and there’d be an invitation on the table to the Emmys, but the person I saw wasn’t that person,” Stephens said. “He was divorced, and he was single and mentally confused about his sexuality. Those changes may have taken all the joy out of his life. Or maybe he was living his life in a way where he just didn’t have rules anymore.

“I feel kind of bad that the media put his sexuality out there and destroyed the product of Elmo,” he added. “I didn’t like the way they put Elmo in every picture with me. What does he have to do with this situation? I mean, Kevin worked for them, but Elmo doesn’t have a sexual organ. Why is everyone going off about Elmo? I didn’t encounter anything with Elmo. It was Kevin.”