Pay Dirt is a weekly foray into the pigpen of political funding. Subscribe here to get it in your inbox every Thursday.

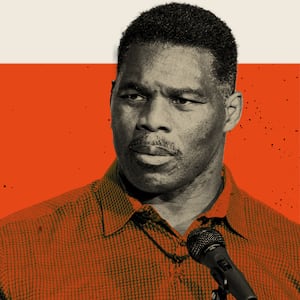

When Herschel Walker emailed a representative for billionaire industrialist and longtime family friend Dennis Washington in March 2022, he seemed to be engaging in normal behavior for a political candidate: He was asking for money.

But unbeknownst to Washington and the billionaire’s staff, Walker’s request was far more out of the ordinary. It was something campaign finance experts are calling “unprecedented,” “stunning,” and “jaw-dropping.” Walker wasn’t just asking for donations to his campaign; he was soliciting hundreds of thousands of dollars for his own personal company—a company that he never disclosed on his financial statements.

Emails obtained by The Daily Beast—and verified as authentic by a person with knowledge of the exchanges—show that Walker asked Washington to wire $535,200 directly to that undisclosed company, HR Talent, LLC.

And the emails reveal that not only did Washington complete Walker’s wire requests, he was under the impression that these were, in fact, political contributions.

In the best possible circumstances, legal experts told The Daily Beast, the emails suggest violations of federal fundraising rules; in the worst case, they could be an indication of more serious crimes, such as wire fraud.

But Walker—who had been schooled on campaign finance rules since his campaign launched in August 2021, according to a person involved in those conversations—appears to have dismissed the Washington team’s concerns that the money may have gone to the wrong place. When a third party informed a Washington Companies executive that the money couldn’t be used for political purposes, they raised the issue with Walker, asking at one point whether the funds should be redirected to a super PAC supporting his candidacy.

Walker never contributed any of his own money to his campaign, according to Federal Election Commission filings, and it’s unclear what happened to these particular funds. Walker may have ultimately returned the money to Washington, but he did not reroute the money to the super PAC, according to FEC filings and a person with direct knowledge of the events.

(A day after this story was published, a spokesperson for Washington said Walker had refunded the money but did not respond to questions about when that happened.)

“It was good talking with you today,” Tim McHugh, executive vice president for the Washington Corporations, wrote to Walker last November. “After our call, [redacted] reached out to me and said [a person] clarified with you that any funds sent to the HR Talent account cannot legally be used for political purposes. Political contributions must go to either the Team Herschel or 34N22 accounts.”

34N22 was a super PAC supporting Walker. Walker was not allowed to solicit donations for the super PAC in excess of federal limits, which this amount of money explicitly was. But that was not McHugh’s concern; he was worried about the hundreds of thousands of dollars his boss had wired to HR Talent in March.

“We will need your assistance to get the prior contributions made to the HR Talent account in March corrected,” McHugh concluded in the email.

While Walker’s campaign was battered from the jump by a hurricane of controversies, this situation stands out.

According to the legal experts who spoke to The Daily Beast for this article, this scheme appears to not just be illegal—it appears to be unparalleled in its audacity and scope. The transactions raise questions about a slew of possible violations. In fact, these experts all said, the scheme was so brazen that it appears to defy explanation, ranking it among the most egregious campaign finance violations in modern history.

Saurav Ghosh, director of federal reform at Campaign Legal Center, called the arrangement “jaw-dropping.” Jordan Libowitz, communications director at Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, said if Walker “used the campaign to funnel money into his own business, that’s one of the biggest campaign finance crimes I’ve ever heard of.” Brendan Fischer, a campaign finance lawyer and deputy executive director of Documented, remarked that the exchanges were “stunning and, to my knowledge, without parallel in recent history.”

“Campaign finance laws are designed to prevent massive under-the-table payments like those described here,” Fischer said. “While we don’t have all the facts, these emails point to highly illegal, potentially even criminal activity.”

Paul S. Ryan, a campaign finance specialist and deputy executive director at the Funders’ Committee for Civic Participation, said the situation suggests a “criminal violation” that is “extraordinary and unprecedented in my 25 years of campaign finance watchdog work.”

“There’s no legal way that this could have played out,” Ryan said.

Neither Walker nor his wife, Julie Blanchard, returned The Daily Beast’s detailed request for comment. Representatives for Washington also didn’t reply to The Daily Beast’s questions.

Federal law prohibits candidates from converting campaign donations to personal use. The law also limits how much money individuals can contribute to a campaign, as well as how much candidates can solicit from donors. Candidates also cannot solicit, accept, or facilitate contributions in the name of another person.

According to legal experts, campaign finance violations become criminal if the violation was “knowing and willful”—essentially, if the person understands the laws.

At the time of the first email, Walker had already been a candidate for half a year, raising millions of dollars along the way. And he was repeatedly coached on fundraising limits and restrictions since the beginning of his campaign, according to a person involved in those conversations—a fact that is demonstrated in the emails when Walker provides a breakdown of federal donation limits.

The Daily Beast reported last month that Walker’s wife, Julie Blanchard—out of concerns about the campaign’s impact on their income stream—tried to personally profit from the campaign. But Walker staffers repeatedly waved her off. Walker claimed a net worth between $29 million and $62 million, according to his most recent personal financial disclosure. Last year, he reported an income in excess of $4 million.

The Washington emails explicitly raise the issue of wire fraud, legal experts told The Daily Beast, if Walker falsely represented his intentions for the money, saying they were for the campaign while in fact they were for his company. But if he did use the money to support his political activity, that would also trigger a separate slate of legal questions, because Walker never reported spending any of his own money on his campaign.

“It’s the frying pan or the fire,” Ghosh said.

In all, the emails indicate that Walker solicited a combined $700,000 in political contributions from the Washingtons, instructing that more than $600,000 of that amount be wired directly to one of his companies, HR Talent.

“That sounds like a criminal violation of the ‘soft money’ ban,” Ryan said. “It is illegal for a candidate for federal office to solicit or direct money outside of federal contribution limits. Even if the money wasn’t spent in the election, Walker would have broken the law when he directed this donor to give money above contribution limits in connection with the election.”

Washington also gave significant money to 34N22—Walker’s super PAC—making a $500,000 contribution days after Walker initially asked for the $535,200, Federal Election Commission records show.

A super PAC representative confirmed that the $500,000 came from Washington directly. And according to a person with direct knowledge of the events, that $500,000 didn’t come out of the $535,200—they were two separate transactions. That would indicate that, at least for eight months, Walker’s company directly pocketed the $535,200.

The first of the emails obtained by The Daily Beast were timestamped 9:39 p.m. on March 1, 2022. It came from Walker’s personal AOL account, and was addressed to Jerry Lemon—chief financial officer at the Washington Companies—with Blanchard copied at her Mac.com address.

The subject line read, “Wire Instructions for Team Herschel People’s Champion Committee,” a reference to a joint fundraising committee for the Walker campaign (“THPCC”). The email directed Lemon to send a combined $600,000, with most of it going to Walker’s company, HR Talent.

“The wiring instruction for the $64,800 is below,” the email said, and instructed Lemon to contact a campaign fiduciary about those donations.

“The $535,200 can be wired to H R Talent,” Walker’s email continued. He provided the name of two banks—one of which also holds a personal account of Walker’s valued up to $50,000, according to his disclosures—along with account and routing information. The message also instructed Lemon to “send the information to Denise Stokes”—Walker’s sister.

A few days later, Washington donations rolled in. FEC records show that the $64,800 appears to have been split into six even donations to THPCC in the maximum allowable amount, attributed to Washington, his wife, his two sons, and their wives.

It’s unclear what happened to the $535,200. But nine months later, Walker was asking his friend for still more cash.

In that Nov. 29 email, McHugh confirmed that, in March, the Washingtons had wired what they believed were campaign contributions to Walker’s personal company. While McHugh asked about redirecting the money HR Talent had received to Walker’s super PAC—to make sure they “get the funds to the right spot”—Walker didn’t address that question in his response. Instead, he just reiterated that more money, nearly $100,000, should be sent straight to his company.

The numbers suggest that Walker had worked out a $100,000 arrangement with each Washington, with 95 percent of their contributions going to Walker’s company instead of the super PAC. But while Dennis Washington’s $5,800 campaign donations from the time do appear in FEC records, the $95,400 never hit the super PAC’s account. Kyle and Kevin Washington did not donate any money after the November emails.

McHugh’s email ended by asking Walker to rectify the original transfer to HR Talent, but it’s not immediately clear whether Walker refunded the money—or whether the two sons were owed refunds out of the original $535,200.

It wasn’t the only boost Washington gave his friend’s campaign.

Washington and Walker go way back. A person familiar with their relationship recalled a close relationship, including extended family vacations. And according to this person, Washington played an instrumental role in securing Walker a coveted award while his campaign was in full swing.

On April 7, 2022, Herschel Walker’s Senate campaign announced that the former college football hero would receive the Horatio Alger Association’s prestigious annual award, “dedicated to leaders who through hard work, honesty, and determination have overcome great obstacles in their lives.”

(As for the campaign’s testament to Walker’s honesty, The Daily Beast revealed months later that the candidate had been repeatedly lying to his top brass—including about the existence of some of his own children.)

While the campaign made political hay out of the moment, it didn’t put Walker over the top. He lost to Democratic incumbent Sen. Raphael Warnock in a December runoff election.

Last month, however, it came full circle. The Walker campaign reported a $250,000 charitable donation to the Horatio Alger Association. But the organization did not list the campaign’s gift on its donor page this year. It did, however, list Walker and Blanchard as personal sponsors at the $250,000 tier. It’s unclear whether Walker was taking personal credit for his campaign’s gift, or if he’d contributed separately.

As for the fundraising solicitation, legal experts pointed out several issues with the arrangement.

Ryan, of the Funders’ Committee, said that Walker’s email explaining fundraising limits—along with the fact that Walker had by that point received months of counseling on fundraising regulations—is “strong evidence that Walker knew what the law prohibited and solicited this money nonetheless.”

“That would make this a crime, if it’s done knowingly and willfully,” he said.

Fischer, of Documented, concurred, saying the email “does seem to lay out knowledge of campaign finance regulations and then offers ways to explicitly get around those regulations. It sure sounds like a knowing and willful violation of campaign finance law, which would make this criminal.”

He also raised the question of how the money was spent.

One scenario, Fischer said, “is that the $535,000 gift was used to cover personal expenses.” If so, he continued, that could violate provisions in the ban on personal use, saying that statute is particularly relevant because those violations have previously sent people to prison.

Fischer pointed to 11 CFR 113.1(g)(6) in the U.S. criminal code, under which a payment by a third person of a candidate’s personal expenses during the campaign is a contribution.

“Payments by a third party made for the purpose of influencing an election and that are coordinated with a candidate or their agent result in a contribution, subject to limits and reporting requirements,” he explained. “Giving over a half million dollars to a candidate is potentially an excessive and unreported contribution. This is a very serious violation of campaign finance law, and it is still a violation if the funds were used for personal expenses instead of campaign expenses.”

While Walker and Washington are close friends, Fischer said it could be tough to argue that the payment would have been made even if Walker weren’t running for office.

“Here, perhaps the donor can show a series of similar payments that began before Walker became a candidate, but even that may not be dispositive,” Fischer said. He called the emails “strong evidence” that the solicitations and payment were for the purpose of influencing the election.

Libowitz called the scheme “brazen in a way that we’ve never seen,” distinguishing it even from Donald Trump’s efforts to enrich himself by spending campaign cash at his businesses.

“It’s not like Trump, because Trump’s campaign isn’t prohibited from spending money at his own businesses as long as he’s paying market rates and there were services rendered,” Libowitz said. “Here, the money isn’t being spent by the campaign on Herschel’s businesses. The money never even goes to the campaign. It just goes straight to him.”

Ghosh, of the Campaign Legal Center, agreed that Walker appears to have violated campaign finance laws, calling the scheme “$500,000 of grift.”

“It appears to be a fake campaign solicitation, designed to just profit personally from someone. That’s brazen in a way that’s off the charts,” he said.

He also pointed out that Walker didn’t disclose HR Talent, LLC in his candidate financial statements—yet another significant issue.

“A federal candidate has to disclose their personal assets, including any sources of income, so failing to disclose a company or a personal bank account would violate the legal requirement and deny voters crucial information about the candidate, undermining electoral transparency,” Ghosh said.

According to Georgia business records, HR Talent, LLC was first registered in the state in 2002, as “Renaissance Man Medical, LLC”—a branch of a Delaware company registered that year—with Walker’s signature on the incorporation documents. Three years later, Walker changed the name to “Renaissance Man Marketing, LLC,” then changed it again to “HR Talent, LLC” in 2014.

At the time, Walker was launching a short-lived reality competition show designed to discover entertainment talent in rural communities, which he called “Herschel’s Raw Talent.” The New York Times reported that the show only hosted events in two Georgia counties before it fizzled out. But Walker personally signed annual business registration documents until 2021, when his sister Carol signed. The company lists its address at Walker’s childhood home in Wrightsville.

Ghosh also noted that if Walker had misrepresented the purpose of the payment, “Then we’re in the world of just defrauding somebody.”

“Sounds a lot like wire fraud if the money didn’t make it to the campaign or super PAC,” Ghosh said. “And the fact they tried to do it again shows they’re trying to squeeze this billionaire.”

Former federal prosecutors told The Daily Beast that the situation merits a criminal investigation.

“If Walker represented to a donor that a contribution was intended for his campaign, but it was actually for his personal benefit, it could form the basis for wire fraud,” former U.S. Attorney Joyce Vance said. “Prosecutors would have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that any defendants knowingly devised a scheme to defraud and intended to defraud.”

Vance noted that if a donation was inappropriately channeled through Walker’s company, “an investigation could reveal whether that was a one-off or whether additional activity occurred there,” adding that the omission from his disclosures “could suggest an effort to obscure transactions.”

Former U.S. Attorney Barb McQuade agreed that the facts merit a formal investigation. She explained that, to get a conviction, prosecutors would have to “prove that at the time he extracted the money, he intended to use it differently than what he said he’d do. So you need to show why he said he wanted the money, what he represented to the donor, and what in fact it was used for.”

“That could be fraud, but you need a subpoena to find the missing pieces,” she said.