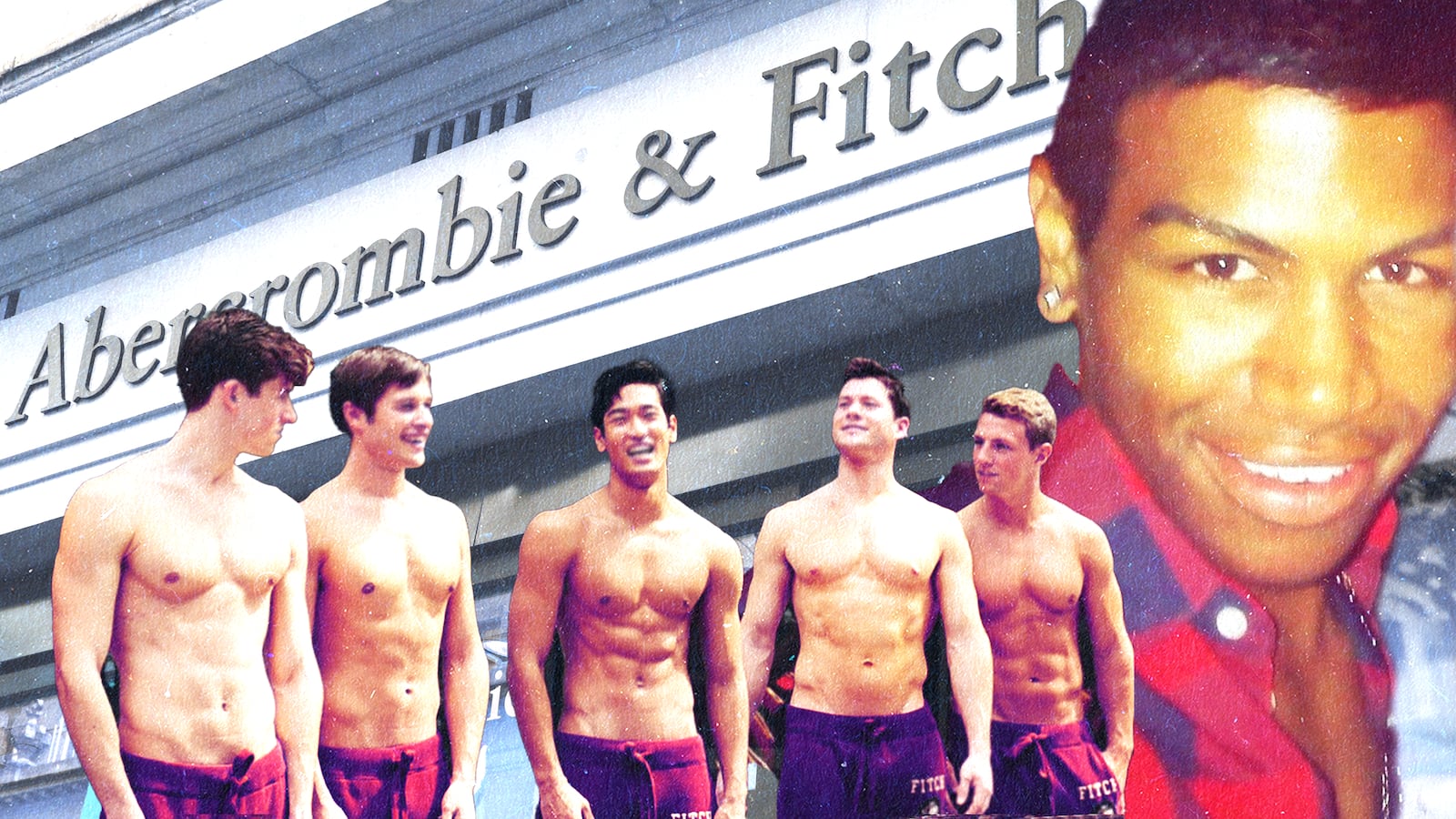

Being an Abercrombie “model” used to mean something. Now we know most of it was just delusion—one that I and millions of other impressionable teens bought into in the early aughts fueled by the bleached-blond desires of the company’s longtime CEO Mike Jeffries.

Jeffries, now 80, was arrested on sex trafficking and interstate prostitution charges on Tuesday, accused along with his alleged life partner Matthew Smith, 61, and accomplice James Jacobson, 71, of luring impressionable young men from small towns into “sex acts” with the promise of superstardom, status and self-respect.

If you were ever “scouted” to work as a model, like I was as a 19-year-old at the height of the company’s chokehold on suburban tweens, chances are you were subliminally promised some version of the same. But the self-respect never came, at least not for me.

In a 2011 incident, a former model named Luke recounted to the BBC that he was 20 years old when he was allegedly invited to Jeffries’ presidential hotel suite in Spain by one of his assistants. The room was dimly lit and decked out to look like an Abercrombie storefront complete with a group of assistants. Luke said he was made to roleplay as a store greeter. “I thought we were going to do a photoshoot,” he told BBC, but it wasn’t long in the exercise before Jeffries and Smith were allegedly all over him.

“I have two very important guests,” Luke said he was told by Jeffries’ assistants. “These are going to be the customers that you need to impress and entertain because they’re going to be buying a lot of clothes from you.”

That encounter—and more outlined in the indictment from 2008 to 2015—“is yet another example of individuals using their wealth, power, or reputation to manipulate and control others for their personal gratification,” said FBI Assistant Director in Charge James E. Dennehy in a statement announcing Jeffries, Smith, and Jacobson’s arrests.

But as shocking as those allegations of manipulation, intimidation and exploitation may seem, they would be much more shocking to me if I hadn’t seen firsthand how Jeffries’ reign over the company influenced all of its employees to operate that way.

In 2008, I was recruited to work as a model for my local Abercrombie & Fitch store in Michigan. I had a good “look,” one of the bleached blond store associates told me. Very quickly I came to learn that it meant that I was f--kable.

Clad in plaid flannel, flip-flops and a faux hawk, and with the store’s signature Fierce fragrance emanating from my pores, I was one of the first people a customer saw when they walked into the store, and I was given similar directives as Luke to “impress and entertain” anyone who came in. Because it wasn’t just clothes we were selling, our store manager Chris once told us: You are selling an image of what people want to be.

During the holidays, I and few other models who were specially assigned to work upfront stood around shirtless offering spritzes of Fierce. We tried on coats and jeans for customers because we were the same size and build as grandsons and nephews. And we were instructed to always smile, have a positive attitude, and avoid the word “no.”

“In every school there are the cool and popular kids, and there are the not-so-cool kids. Candidly, we go after the cool kids,” said Jeffries in a 2013 interview about the company’s retail strategy. “We go after the attractive, all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends.”

Yet behind the scenes, things got ugly quickly. Photos of store associates were regularly taken every few months and submitted to the home office so they could have a record of what employees were working and where. And when the home office sent secret shoppers to test out our store’s atmosphere, we were mostly judged on how we looked and our ability to “accurately represent the brand” in the clothes—aka, look hot.

Whenever someone started not to fit in, they were shuffled to a different role. And as people began to catch on that they were made to work in the stockroom and clean toilets because they weren’t thin, white or athletic enough—or a manager didn’t like their new haircut, which happened many times at our store—the lawsuits started rolling in.

What’s more is Abercrombie preyed on the very thing all gay men craved: exclusivity. And while there were some models who quit working for the company in protest over the working conditions, many more gay men like myself leaned further into the delusion because the store was a place where we—largely discriminated against as outcasts at the time—could rule with our looks and be celebrated as “fierce.”

“Even to go out, I would dress like I was working at the [store],” remembers Luis, one of my former coworkers. “Because I knew that’s what people wanted and had a visual of what someone cool should look like … You know, you just wanted to fit in. Wearing the clothes made you cool, made you feel like one of the people from the pictures.”

Many former Abercrombie employees and “models” have shared stories of discrimination in the Netflix documentary, White Hot: The Rise & Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch. However, none of this happened overnight. Many of us heard the rumors of what was happening and how much of a creep Jeffries was, but most of us still stayed for the prestige and the store discount. Plus, there was always someone who knew someone else who had been plucked from a store to star in one of the company’s ads, which always featured hard-bodied twenty-somethings running through fields.

Of course the real models allegedly had it worse. Many of Abercrombie’s most hypersexualized ad campaigns were shot by disgraced photographer Bruce Weber, who has all but disappeared after five models accused him of groping their genitals during photo shoots for French Vogue and Abercrombie & Fitch from 2008 to 2011.

“I’m completely shocked and saddened by the outrageous claims being made against me, which I absolutely deny,” said Weber, in a statement put out by his lawyer in 2018.

Oklahoma-born Jeffries was a spry 48 when he took control of Abercrombie in 1992, which had filed for bankruptcy and lost its footing as an outdoor equipment retailer that started in 1892. According to him, targeting “everybody” was a business mistake. “Those companies that are in trouble are trying to target everybody: young, old, fat, skinny. But then you become totally vanilla. You don’t alienate anybody, but you don’t excite anybody, either,” said Jeffries in a 2006 Salon interview.

When Jeffries stepped down in 2015, Abercrombie & Fitch Co. did a complete 180 as a company. Gone are the overtly sexual adverts and the overpowering cologne; during a recent trip to pick up a T-shirt, I was pleasantly surprised to see store associates came in all shapes, sizes and colors.

Addressing the allegations about Jeffries that began to trickle out last year, Abercrombie execs said they were “appalled and disgusted.” However, Jeffries has not specifically put out a statement about the claims against him, with his lawyer saying they plan to “respond in detail to the allegations” in the courthouse, “not the media.”

However, when Jeffries was spotted outside a West Palm Beach federal court after being released on a $10 million bond, his looks said a lot. Hair plugs now shocked white but still boyishly combed to the side, a tightly pulled, clean shaven face, a V-neck sweater, shorts, and a new ankle monitor accessory—he looked every bit like an Abercrombie model whose time had come and gone long ago.

And in that moment I felt he represented what we all could do well to learn: f---able is in the eye of the beholder.