“How dare you call me lazy, slobby or undisciplined?” read the stranger’s tweet. I have never written, spoken, or thought those words, but that’s beside the point. These days, simply being slim can be enough to cause offense.

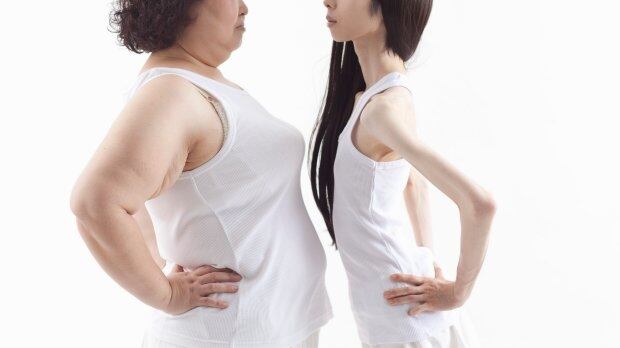

Of course I believe that “fat shaming” is wrong: no one should be mocked for their weight. Public and high-profile cases of fattism (remember Karl Lagerfeld’s comments about Adele?) have caused public outrage—as they should. That’s progress, certainly. But what about the flip side: why is skinny shaming acceptable, if fat shaming is not?

A few years ago when I worked in publishing, we’d gather in our boardroom for weekly meetings to discuss new authors and book proposals. There would be complimentary tea, coffee, and platters of pastries on the table. A senior colleague—a lovely woman in her 50s—would always urge me, loudly and publicly, to have a croissant. She would prod me in the side, in a seemingly friendly manner, while commenting: “Look, she’s nothing but skin and bone!” or “We need to feed you up!”

The fact that I was deeply anorexic at the time is irrelevant. The fact that she was overweight is also irrelevant. She was drawing attention to my size in a way that would have been unacceptable had I done the same to her.

I’m aware that I’m treading on thin ice here: what could be more irritating than a skinny person describing another person as fat? And yet—for a moment—think about the terms we use to describe thinness: scrawny, emaciated, angular, bony, skeletal. Such words are casually batted about in the media without any of the caution we must now use in our references to fatness. A recent magazine headline proclaimed: “Curvy Is the New Skinny.” Note the tactful use of “curvy” and the tactless use of “skinny.” I happen to find the term “skinny” offensive, but of course that’s foolish. Cue the eye rolls: You’re lucky to be thin, you think.

I’ve never been teased or socially excluded or called greedy. I’m not a “big girl,” and I don’t have curves. For 10 years, my problem was eating too little, rather than too much, food. What could I, as a recently recovered anorexic, possibly know about fatness?

To start with, I know the experience of feeling that one’s private pain is on display, of being stared at, of feeling horribly conspicuous. I see overt parallels between fatness and thinness. I believe that out-of-control eating may operate in the same way as out-of-control starving—as a defense mechanism against the world, a place to retreat when life feels overwhelming.

When I wrote about these issues in my new book, The Ministry of Thin, I was shocked at the backlash. I’ve discovered that even to hint at the notion that fatness might be anything than a cause for celebration is a big mistake. The plus-size-sisterhood can be frightening—not unlike playground bullies. Among the messages I received (interestingly, only from women, and mostly anonymous), I was called “skinny bitch,” “body fascist,” “fat-Nazi.” I was told that men “love something to grab onto” and that “curves” are sexier than the skeletal look.

And yet my book contains not a single word of criticism about larger-sized people. I employ the word “fat” in a literal sense, to describe the deposits of fatty layers under the skin and around organs, not as a term of abuse. In writing about my own weight struggles, I describe the visceral experience, because I believe people need to know what anorexia feels like. It’s important to understand extreme emaciation—how your tailbone sticks out so you can barely sit on a wooden chair, how your limbs ache from lying in bed with no cushioning, how you bruise easily, and feel cold constantly. How your ribs and hips and shoulder blades become this weird, coat-hanger arrangement of clashing bones.

Apparently we can’t have a rational debate about the reasons behind, and the experience of, obesity. Fat is still a feminist issue, and a fraught one. But I'm fed up with being judged for being physically disciplined, for being careful about what I eat, and for exercising regularly.

Here are some other things a thin woman is not allowed to say: “It takes willpower to stay slim”; “Of course it would be easier just to eat anything I wanted but I don’t”; “Yes, I'm often hungry midmorning but I wait until lunch-time.” And here, above all, is what we must never say: “I prefer being slim.”

I’m not the only woman who feels this way. A friend and fellow journalist says: “it’s incredibly tedious, all this tip-toeing around the issue—if I write anything about weight I’m terrified of causing offense, endlessly having to clarify and explain.” Another friend, herself a size 18, is even more outspoken: “It’s jealousy, pure and simple. Skinny-minnies are fair game because we all want to lose weight.”

It’s not the nasty names I mind, it’s the inevitability of this offense-taking, the speed with which a slim woman is condemned as fattist, and attacked as a “scrawny stick-insect” (another tidbit from my inbox). Why must we be apologetic about the lifestyle we’ve chosen, the food we eat, or the body we want to live in?

While researching my book, I spoke to a woman in the U.S. who weighs around 500 pounds (35 stone). A member of a Fat Acceptance community, she was open and happy to discuss her size. We got on like a house on fire, and I found her optimism refreshing. But I wonder if she’s willfully ignoring the health risks? By any measure, 500 pounds is not a safe weight. I admire her ability to withstand the pressure to look a certain way, but there is a level of self-deception here. Physical extremes, from the very underweight to the very overweight, are stressful for the body, and often mask mental anguish too.

For me, facing up to the health consequences of being underweight really helped put me on the road to recovery. I wasted a decade struggling with the mental roller coaster of anorexia, trapped in a labyrinth of control and starvation. It was only in the last few years, when I found a medical reason to recover—namely, my fertility—that I made progress with gaining weight. Could the same approach work for weight loss? If we reframed the debate around fat and accepted that it can be a form of disordered eating, with physical consequences, we might start to get somewhere.

One man contacted me, and his words have stayed with me: “I was in denial for years … Then I decided I’m not big-boned, I’m fat. I’ve lost 15 kg [33 pounds] since then.”

For now, it’s less of a debate and more of a lion’s den. I’m hardly the first person to wonder why online anonymity breeds such rudeness. If it’s OK for you to be fat and proud of it, it’s OK for me to be slim and proud of it, too. Reading angry emails from strangers, I sometimes feel like T.S. Eliot’s Prufrock: “That is not what I meant at all …”

Emma Woolf is a journalist, TV presenter, and the author of An Apple a Day: A Memoir of Love and Recovery from Anorexia. Her new book, The Ministry of Thin, came out in June 2013. Emma lives in London. Follow her on Twitter @EJWoolf.