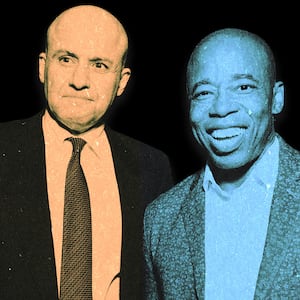

New York City Mayor Eric Adams’ liaison to the United Nations and the city’s foreign consulates has said his mission is to bring international business back to the pandemic-wracked metropolis. But Adams’ image as a crime-busting ex-cop is at odds with the kind of foreign investments his international affairs commissioner, Edward Mermelstein, has been involved in.

Reporting on Mermelstein to date has focused on his former leadership of a nonprofit founded by sanctioned oil and aluminum tycoon Viktor Vekselberg, and his zealous self-promotion last decade as an expert on property acquisitions by the post-Soviet plutocracy. And, indeed, New York corporation and property records show that Mermelstein’s former Manhattan law office sits at the center of a vast web of inscrutable entities controlling some of the most expensive and exclusive real estate in the city.

But Mermelstein is also tied to a figure perhaps even darker than the Putin-aligned Vekselberg: Ukrainian-born former Moscow property magnate Pavel Fuks, a widely sanctioned oligarch whom multiple experts identified to The Daily Beast as an associate of organized crime, and whom a 2021 lawsuit accused of working for Russian intelligence and international drug traffickers.

Fuks, who reported being banned from entering the United States in 2017, became infamous in America last decade as the developer behind an aborted Trump-branded development in Moscow—and as a patron of Adams’ predecessor, Rudy Giuliani.

“Honestly, he’s mafia, it’s the most simple way to say it,” Olga Lautman, senior fellow at the nonprofit Center for European Policy Analysis and an expert on organized crime and espionage in ex-U.S.S.R. states, said of Fuks.

In a statement to The Daily Beast, the mayor’s office noted Mermelstein’s own roots in Ukraine and his fat Rolodex, and maintained he only ever had a “limited business relationship” with Fuks. Adams’ team also asserted that Mermelstein’s service to him predated any allegations of misconduct by the mogul.

“The clients were vetted not only by the commissioner but by banks, lawyers and investors that did their own due diligence,” said Deputy Press Secretary Ivette Davila-Richards. “Obviously the commissioner would not have represented them after the allegations came to light.”

But Lautman told The Daily Beast that connections to Russian underworld figures and intelligence agents—and the two became indistinguishable—were prerequisites for success in Moscow after 1991, particularly during the reign of ultra-corrupt late Mayor Yury Luzhkov, a Fuks ally.

“Pavel Fuks was doing business with pretty much all of them since the 1990s,” she said.

Anders Aslund, an economist and former adviser to Russian and Ukrainian administrations, agreed that mob ties are essential for property development firms like Fuks’ Mos City Group.

“If you are in real estate you are in organized crime,” Aslund told The Daily Beast. “You can’t stay away from it.”

A 2018 Al Jazeera profile described how Fuks earned the nickname “the Mercenary,” boasted on television of physically brutalizing those who refused to obey him, and engaged in property and financial deals with an array of known fraudsters and criminals.

It’s real estate also that connects Fuks and Mermelstein: a pair of deals not in one of the glittering districts of Moscow, but along one of the most coveted avenues in New York.

On Nov. 15, 2013, Fuks’ wife, Tatiana Kudina, signed mortgage paperwork for a $4.8 million condominium at 15 Central Park West which “irrevocably designates and appoints” Mermelstein as her agent, making him her lawyer and representative. That exact day, she inked other documents accepting her husband’s power of attorney, which Fuks had signed over to her in Russia just three weeks before.

Documents filed in New York courts show that it wasn’t the first time the power couple did business with Mermelstein—or at 15 Central Park West. A short-lived and amicably resolved lawsuit Kudina filed in 2012 revealed she had loaned $3 million to another Mermelstein client to purchase another unit in the building, with Mermelstein’s firm acting as escrow agent. (The suit also revealed that British historian Andrew Roberts, an adviser to various right-wing think-tanks and to ex-President George W. Bush, was residing in the apartment with his wife at the time of the suit. Roberts declined to comment.)

Before dropping her suit, Kudina sought to compel Mermelstein’s firm to disgorge her stake in the apartment into a bank account belonging to BEM Global Corp. Materials revealed in the Panama Papers leak showed that BEM Global is a shareholder in a Fuks-linked company, Dorchester International, and English and Russian-language reporting has identified BEM Global as belonging to Fuks’ brother, a frequent business partner.

In 2015, Barclays bank reported to the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network a $1 million payment BEM Global made to the former deputy mayor of Moscow, a disbursement the lending institution deemed “suspicious,” given the official’s oversight of one of the brothers’ signature real estate projects. It is unclear how or whether U.S. authorities reacted to this flag. But Fuks’ activities would only fall under greater and greater legal and popular scrutiny in the years ahead.

Fuks was one of a number of figures to come to the attention of special counsel Robert Mueller, due to his efforts to illegally obtain tickets to ex-President Donald Trump’s 2017 inauguration, which foreign nationals are not allowed to purchase. Fuks had traveled to the United States for the event with a Ukrainian parliamentary ally of former President Viktor Yanukovych, a puppet of Russian President Vladimir Putin, and the pair were photographed together with House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy.

Fuks provoked even more questions when he revealed that he had engaged in negotiations in the 2000s with the Trump family over the construction of the long-dreamed of but never-realized Trump project in Moscow—and the mystery only thickened when the Washington Post discovered Fuks had testified in court that he was banned from entering the United States, without providing any reason for his exclusion. The Post report was one in a flurry of news stories about Fuks’ payments to Giuliani for work on behalf of his hometown of Kharkiv, Ukraine, where Fuks had returned in 2015 and swiftly developed a close bond with the city’s Russia-aligned then-mayor.

In 2018, Ukrainian prosecutors probed Fuks’ alleged acquisition of assets belonging to Yanukovych held in companies based on the island of Cyprus—a notorious sanctuary for dirty money—and believed to have been stolen from the country. In early 2019, Ukrainian news outlets tied Fuks to a massive heroin ring busted in Kyiv, and cited law enforcement sources claiming that the developer had funneled the drug into Ukraine out of Central Asia.

It is unclear how these investigations were resolved, but in 2021, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s administration sanctioned Fuks along with Putin ally Dmytro Firtash, alleging Fuks had improperly obtained fossil fuel extraction permits from the Yanukovych regime. Fuks, by then operating in the capital of Kyiv, asserted that the charges were politically motivated attacks from rival businessmen.

Later that year, Fuks—who had once received an award from Putin for his contributions to the Russian economy—found himself on a list of Ukraine-based businessmen hit with Russian sanctions, making for what the U.S. think-tank the Atlantic Council called one of “the most surprising inclusions.” In 2019, he was arrested in absentia and charged with fraud in a Moscow court.

Aslund, the economist and former Russian and Ukrainian policy adviser, described Fuks as a “confused person” who has repeatedly reoriented his loyalties, most recently against Russia and toward Ukraine. CEPA’s Lautman was more cynical, labeling the Russian sanctions and charges “B.S.” and arguing that they were intended to give Fuks cover to covertly advance Moscow’s interests in Ukraine.

“They’re more for the West, to create this facade: that this person's under prosecution, he's an enemy of the Russian government,” Lautman said.

A lawsuit Republican fundraiser and lobbyist Yuri Vanetik filed against Fuks last year backs up this assessment. The civil complaint asserts that Fuks is “an agent of Russian intelligence services” and that “since 2015 Fuks fled to Ukraine for good but maintained his relationship with Russian intelligence services and authorities,” and also serves as an “earner” for Russian drug cartels. Fuks, who sued Vanetik in 2019 for failing to deliver his illegal tickets to the presidential inauguration, has called this suit “nonsense.”

The most recent attorney on record for Fuks, who has represented him in his case against Vanetik, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Mermelstein’s law firm, which maintained an office in Moscow, served thousands of other clients whose identities remain cloaked in corporate obscurity. By his own admission in past interviews, much of the business came from individuals working in the Kremlin-controlled oil industry and impacted by sanctions and instability following the first Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014.

But Mermelstein’s service to Fuks, on its own, disturbed Lautman.

“You don’t become the lawyer for Pavel Fuks’ wife out of nowhere,” said Lautman. “For a U.S figure who is in government to have these kinds of relationships, that is very troubling, and it should not be allowed.”