What more could there possibly be to say about the case of Jeffrey MacDonald, the Green Beret doctor convicted of the evil murder of his wife and two small daughters? It has been the subject of a book by Joe McGinniss, Fatal Vision, which sold over five million copies and was turned into a highly popular TV miniseries; a 60 Minutes program watched by 30 million; and even an iconic book, The Journalist and the Murderer by New Yorker writer Janet Malcolm that examined the relationship between McGinniss and MacDonald.

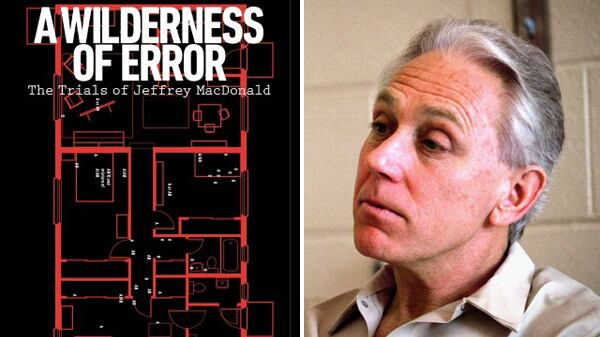

“Millions of words have been spoken, written, read—affidavits, court transcripts, lab reports, videotaped interviews, newspaper articles, and now even blogs,” notes Errol Morris. And yet, 42 years after the crime, Morris, the Academy Award-winning documentary filmmaker, has added his considered reputation to the case with a 500-page opus, enriched by chronologies, casts of characters, drawings, photos.

Why? Because Morris, whose notable achievements in the pursuit of justice and exposing government abuse include Standard Operating Procedure, about Abu Ghraib (co-authored with Philip Gourevitch), is convinced there has been a gross miscarriage of justice, that MacDonald is innocent. Morris argues, with varying degrees of success, that investigators, prosecutors, judges, even MacDonald’s defense lawyers, as well as journalists, are complicit.

Briefly, the facts of the case (as only someone under 50 may need to have recounted) are that in the early hours of Feb. 17, 1970, the bloodied, battered body of MacDonald’s four-months-pregnant wife, Colette, was found on the floor of their home on Fort Bragg military base. Her arms had been broken, her skull fractured, and she had been stabbed multiple times in her chest and neck. His daughter, Kimberly, 5 years old, had been stabbed, her head crushed with a club. Two-year old Kirsten was stabbed to death.

MacDonald told military investigators that he had been asleep on the couch when he was awakened by screams. He claimed that three men, one black, and a woman wearing a blonde wig and a floppy hat, who was carrying a candle, broke into the house around 4 AM. They were shouting “LSD is great,” MacDonald said. “PIG” was written in blood on the headboard of the couple’s bed. Ten weeks earlier in in Los Angeles Charles Manson and his drug-crazed followers had murdered seven, including Sharon Tate who was eight months pregnant, and written in blood on the walls.

Military investigators quickly concluded MacDonald had perpetrated the crime, but after a preliminary hearing, the military decided there was not enough evidence to court-martial him. He was honorably discharged, and moved to California where he worked in the emergency room, earning praise from colleagues. That would have been the end of the MacDonald story, except that his father-in-law, Freddy Kassab, who had originally been a staunch believer in MacDonald’s innocence, turned on him and pressured the Justice Department to prosecute. After a six-week trial, in 1979, the jury after deliberating six hours found MacDonald guilty, and he was sentenced to three consecutive life terms.

MacDonald is a victim, in Morris’s construct, of a narrative adopted at the outset by Army investigators—he is guilty—which has been too willingly accepted by the public ever since. It is a narrative grounded in evidence that has been “rejected, suppressed, misinterpreted,” Morris says.

There are many deeply disturbing aspects to this case, which Morris exhaustively documents. The Army investigation was so badly mishandled that the FBI wouldn’t go near the case. MPs tramped through the blood-soaked house, pieces of vital evidence were moved, obvious places for fingerprints weren’t dusted, such as Colette’s jewelry box from which items were missing, and other fingerprints were destroyed. Once the case reached the federal courts, Morris finds overzealous prosecutors more determined to get a conviction than to uphold justice—a not uncommon mindset among prosecutors, as recently witnessed in the case of Edward Lee Elmore, an innocent man sent to death row for 28 years as a result of prosecutorial misconduct, including evidence that was almost surely planted. (A case about which I wrote a book, Anatomy of Injustice.)

Morris says there is “no proof” of MacDonald’s guilt. But in law, evidence is considered proof, and there is plenty of “proof/evidence” of MacDonald’s guilt. The question is whether it is enough to prove MacDonald’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. “It is possible to cherry-pick evidence to support any conclusion.” Morris says. “And it is possible to interpret evidence to support a conclusion.” He is right, of course. But that is precisely what he does in his narrative unfolding from the belief that MacDonald is innocent.

One of the main characters in Morris’s narrative is Helena Stoeckley. She was a drug-addled hippie, a daily user of heroin and LSD, and into witchcraft, who may have been the woman in wig and floppy hat, if there was such a woman in the room, which Morris believes there was.

Over the years, she told different stories. To some, she said she was in the house; to others, she only thought she was in the house. When MacDonald’s lawyers interviewed her, Stoeckley described what she had seen inside the house at the time of the crime. Two days later, when the lawyers put her on the stand, she admitted to taking mescaline the night of the murder, but didn’t remember telling Segal anything indicating she had been in the house.

Morris sees a conspiracy here, which is somewhat hard to follow. The reasons Stoeckley changed her mind and testified in a manner that did not help the defense, Morris says, was because following her interview with Segal, she had been threatened with prosecution if she admitted to being at the crime. While that sadly would not be surprising, Morris’s principal basis is an affidavit by a federal marshal that he had heard the U.S. attorney make the threat. The U.S. attorney denied it, and said the marshal had not even been present when he interviewed Stoeckley. “Cherry picking the evidence,” Morris chooses to believe the marshal.

And there is the coffee table—“the impossible coffee table,” Morris calls it. It was found on its side. Prosecutors cited this position as evidence that MacDonald had staged the crime scene. If there had been intruders and a struggle, the top-heavy coffee table would have landed on its top, legs up, investigators said, based on their own experiments shoving the table. The military officer who conducted the preliminary investigation, however, conducted his own experiment, kicking the table, and it landed on its side. “Cherry-picking” evidence, the state chooses to believe the investigators; Morris sides with the military officer.

Morris goes on that even if the coffee table had been placed on its side, “what does it ultimately tell us about MacDonald’s guilt or innocence?” The answer is that it is evidence for the jurors to weigh in deciding MacDonald’s guilt or innocence. But Morris doesn’t seem to think much of the trial system. It is a “magic show,” he says, “based on appearances and logical fallacies and sleight of hand. It isn’t about proof. It is about convincing the jury.”

This is lyrical writing, masking how the system works. A trial is definitely about convincing the jury (what’s wrong with that?); the prosecution offers “proof,” the defense offers “proof,” and both use appearances, logical fallacies and sleight of hand.

Just as evidence can be “cherry-picked,” Morris notes that the same evidence can be exculpatory or inculpatory depending on prism through which it is viewed. At one point, a U.S. attorney asked the local FBI agent to investigate Stoeckley, and another individual, “so as to eliminate any possibility of their being possible suspects.” Through his prism—MacDonald is innocent—Morris interprets this to mean that the U.S. attorney was determined to exonerate them so that he could prosecute MacDonald, and Morris may be right. But another reasonable interpretation would be that the U.S. attorney didn’t want to proceed with an indictment of MacDonald if Stoeckley was the perpetrator. Choose your narrative, get your exculpatory/inculpatory interpretation.

In his narrative, Morris is sometimes on shaky grounds when it comes to the law. He says the judge should have given Stoeckley a lawyer as soon as she was summoned as a material witness; and that when the judge did give her a lawyer, after she had testified, it was because he wanted to silence her in the future. But there is no law requiring a material witness to be assigned a lawyer, and the judge gave her one as soon as she requested.

Morris says that the judge, whom he calls a racist, had a conflict of interest: he ex-son-law had been a U.S. attorney who investigated the case in its early stages. This is a tenuous conflict, at best—the “ex” husband was also no longer in the U.S. attorney’s office—and Morris cites no legal authority that the judge should have recused himself.

At MacDonald’s trial, the prosecution had two experts, a psychiatrist and a psychologist, “in its back pocket,” Morris says. On the stand, they said “what the prosecution wanted them to say.” Where does he think the defense has its expert witnesses? And woe to the defense lawyer who puts an expert on the stand not knowing what he is going to say.

MacDonald had better defense counsel, and more money spent on his defense, than probably 99 percent of the men charged with murder. But Morris censures MacDonald’s lead counsel, Bernard Segal. His closing argument was a “desultory mess,” so bad that he lost the case. Morris goes so far as to suggest that with a different lawyer, MacDonald might have been acquitted.

With this book, Morris appears to be trying to repeat A Thin Blue Line, his award-winning documentary exposé of a man convicted of a crime he didn’t commit. Whether he succeeds with Jeffrey MacDonald will be for readers to decide.