The Boeing 737-MAX is not likely to be pronounced safe to fly any time soon. The Daily Beast can reveal that the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) is withholding certification that the airplane is airworthy until its own pilots have tested technical fixes proposed by Boeing.

This comes immediately in the wake of a damning multi-agency task force report on how Boeing and the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration handled the original testing and safety certification program for the new jet.

An EASA spokesperson told The Daily Beast, “EASA has concerns regarding the consequences of angle of attack sensor failures at aircraft level, and the ability of the flight crews to cope with the situation in critical phases of flight (such as take-off).”

They added, ”EASA intends to conduct its own test flights separate from, but in full coordination with, the FAA. The test flights are not scheduled yet, the date will depend on the development schedule of Boeing. We will send our own pilots.”

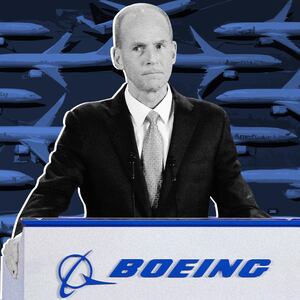

In September, Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg told a conference of investors that Boeing was making “good, solid progress” on fixing the flaws in the flight control system and that he was “still targeting early fourth quarter for return to service.”

In contrast to that statement, the combination of the multi-agency review of failures in the safety certification process conducted by Boeing and the FAA that led to two crashes, and the tough line being taken by EASA, are prolonging the biggest crisis ever to hit Boeing. They are also prolonging the costly consequences of the grounding to airlines that were flying hundreds of 737-MAX model.

The crashes together cost the lives of 346 people.

In fact, the concerns of EASA and the U.S. task force converge on the same basic issue—the sudden stresses placed on the pilots in the two crashes by a chain reaction of failures in the flight controls.

These began with the angle of attack sensors cited by EASA, which are used to warn of the approach of an aerodynamic stall. The sensor fed false data into the airplane’s computers and that false data, in turn, activated a new system called MCAS, Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, that Boeing had decided that pilots did not even need to know existed.

Even after the first crash of a three-month-old jet flown by the Indonesian carrier Lion Air on October 29, 2018, killing 189 people on board, the 737-MAX remained in the air. The FAA still considered it safe. Not until the crash on March 10 this year of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, involving another newly delivered 737-MAX in similar circumstances, was the airplane finally grounded—and even then the FAA was the last to act, days after China, Singapore, Australia, and Europe.

Both crashes involved a sudden and terrifying nose dive—into the Java Sea in the case of Lion Air and into the ground in the Ethiopian crash. And in both cases the pilots’ actions were overridden by the rogue MCAS system.

At the time of the Lion Air crash, pilots flying the MAX model were not informed that MCAS existed and it was not included in the flight manual. Although the Ethiopian pilots were informed of the system and knew what had happened to the Lion Air pilots, they were still unable to regain control.

The U.S. report reveals a long sequence of muddied communications between Boeing and the FAA inspectors charged with insuring the safety of the new model, including evidence that Boeing had failed to keep the FAA informed of changes made to the MCAS system as it was being developed—even though the system required “functional hazard assessment.”

The report also emphasizes how many of the problems in the development of the MAX arise from the attempt to marry new technology to a cockpit design that dates from the '60s—something that The Daily Beast has previously cited as basic to the airplane’s serious flaws.

Similarly, the director of EASA, Patrick Ky, told European lawmakers in September that Boeing had not given “an appropriate response” to address safety issues and he said there was “still a lot of work to be performed” before EASA decided that the airplane was safe to fly.

EASA told The Daily Beast, “We are not being prescriptive in the way that these concerns should be addressed, it could be through improvement of the flight crew procedures and training, or through design enhancements, or a combination of the two.”

More than 42 airlines around the world have fleets of the 737-MAX that are grounded. The two largest users of the MAX in the U.S. are Southwest and American. American said recently that it hopes to have its jets back in the air in January.