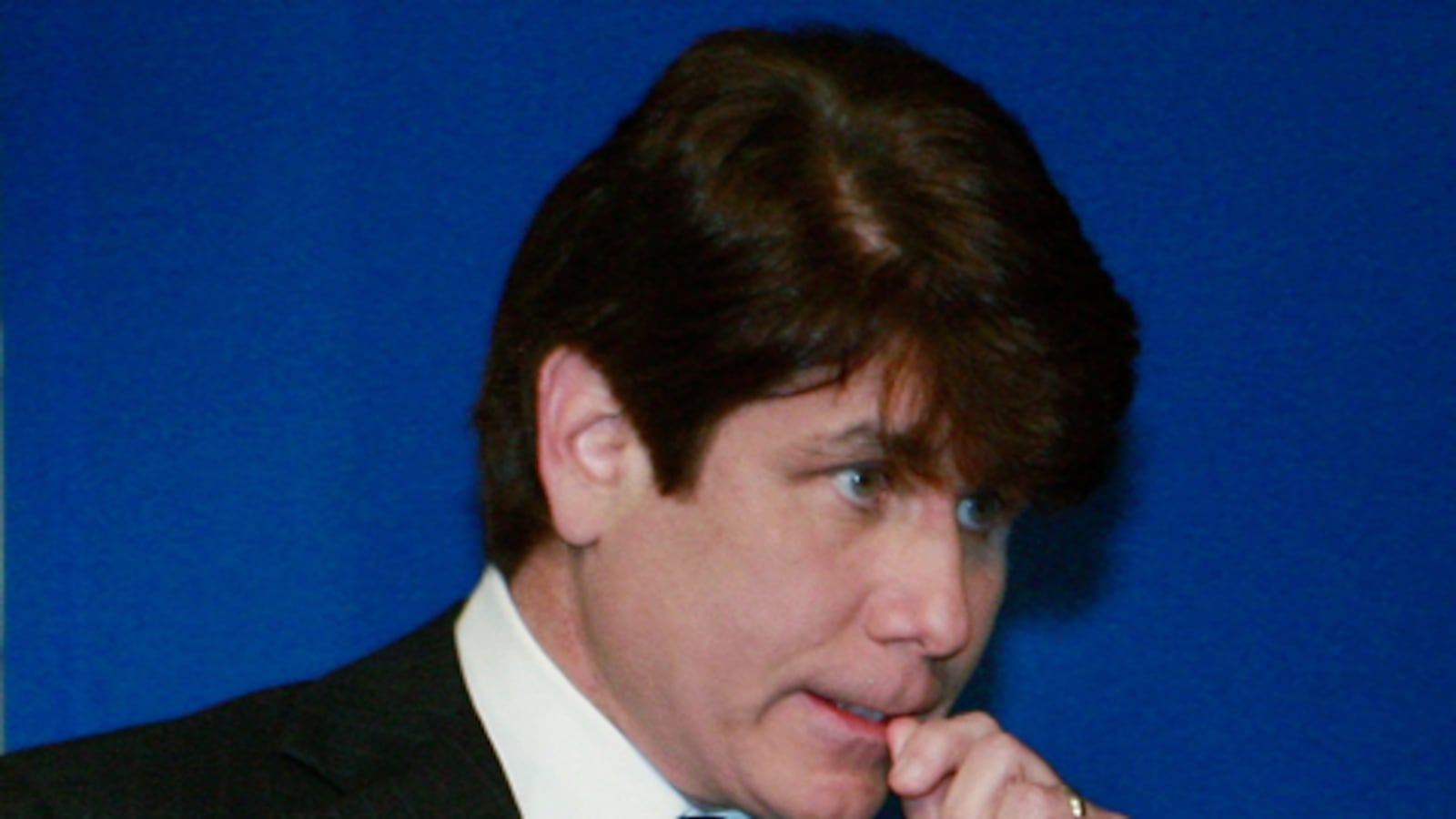

Governor Rod Blagojevich’s press conference on Friday was short on details but long on cheerleader rhetoric (“I will fight, I will fight, I will fight”) and was meant to create the impression that the governor actually has a chance in the forthcoming criminal prosecution that will be mounted by United States Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald. Long story short: Blago is toast. Fitzgerald’s need to charge the case earlier than he might have liked poses some practical problems for him and his staff. But there is no question that he will bring a compelling case, neigh on to invincible.

For the moment, Blagojevich and his artful and much-admired defense lawyer, Ed Genson, who recently successfully defended hip-hopper R. Kelly and unsuccessfully represented press lord Conrad Black, are willing to play every trump. The state of Illinois—both its legislators and citizens—desperately want to move forward. We need a U.S. Senator to replace Barack Obama and the General Assembly wants to move forward on a lengthy legislative agenda, led by a growing public demand to put an end to Illinois's reprehensible practice of unlimited campaign contributions, which all but four states in the country indulge in.

The only real defense for Blagojevich is to blame those quid pro quos on his aides and fundraisers and claim he was clueless.

Because Fitzgerald will not allow the General Assembly to delve into the evidence he has gathered, the Illinois House impeachment committee will end up having to charge Blagojevich for a wide range of abuses and lesser offenses. The legislators are acting responsibly so far and are reluctant to set a precedent that will allow a political majority to oust a Governor of the other party. Genson will demand due process for his client and the members of the General Assembly, no matter how angry they are, will do their best to allow Blagojevich to offer a defense. My guess is that it will be about four months before Blagojevich is ready to face trial in the state Senate.

All of this will give Blagojevich some leverage. At the end of the day, as his impeachment draws near, Blagojevich, who admitted a near desperation for money on the federal wiretaps, is likely to choose to take a leave of absence with pay, rather than getting thrown out of office and going to trial broke. But none of that means that the case Fitzgerald will bring by way of indictment in early January is really in trouble.

Some commentators have argued that the prosecution of Blagojevich, especially the charges that he was trying to sell Obama’s Senate seat in exchange for a job or massive campaign contributions, is not all that compelling. And it is surely true that it is hard for prosecutors to win cases of attempted bribery. So-called ‘crime in the head’—bad thoughts without outright bad conduct—does not tend to impress jurors.

But critics should not make the mistake of confusing a bare attempt case with the forthcoming indictment against Blagojevich. What Fitzgerald charged in the complaint is an astonishing and appalling pattern of extortion and bribery involving numerous completed crimes. Blagojevich awarded state contracts and state jobs to giant campaign contributors. The only real defense for Blagojevich is to blame those quid pro quos on his aides and fundraisers and claim he was clueless. And that dog will not hunt. Not only does the government have at least four witnesses who were deep in the scheme who will say that Blagojevich was fully knowledgeable, but the roster of witnesses of is all but certain to grow as Blagojevich intimates caught on the wiretaps make their own deals over time. Worst of all for Blagojevich is the venal chatter that came out of the governor’s mouth and was captured on the federal bugs that were in place for over a month. The man who called the President-elect of the United States a “motherfucker” because Mr. Obama’s team wouldn’t play ball, will be damned in the end by his own words and his unambiguous intent to profit from public office.

That said, Fitzgerald will not have the same ease in tidying up his case against Blagojevich or in prosecuting all the lesser bad guys he would have liked to sweep up had he been able to charge Blagojevich on the more leisurely time table he had in mind. Instead he was forced to take down the governor to prevent him from selling off the Obama seat and engaging in other pay to play acts, like signing a bill that would give the state horse racing industry a piece of riverboat casino revenues.

Fitzgerald now has 20 days—not including weekends and holidays—from the arrest on December 9 to indict Blagojevich. After that, the law prohibits him from using the grand jury to investigate the offenses he has cited. Fitzgerald will remain free to look into uncharged crimes and uncharged individuals with the assistance of the grand jury, but he will have to tread carefully.

The reason is that the grand jury is superintended by the Chief Judge of the federal court in Chicago, the Honorable James Holderman. For decades, the U.S. Attorneys in Chicago had virtual carte blanche in their use of the grand jury, but Judge Holderman is one of those old-time Republican appointees who believes in the Constitution and who toes a more restrictive line with the U.S. Attorney’s Office than many of his predecessors. The relationship between Fitzgerald and Holderman grew so rancorous a few years ago that the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit ended up wagging a finger at each of them. Both the Chief Judge and the U.S. Attorney are brilliant lawyers, consummate professionals and dedicated public servants, and they have rebuilt their relationship with mutual respect. But Fitzgerald knows that he will have to proceed with caution to let Genson engage in extensive motion practice that will imperil the prosecution at the same time he attempts to grind any post-indictment grand jury activities to a halt.

For the time being, the soap opera will go on. But sooner or later, Lieutenant Governor Pat Quinn will become governor and is likely to appoint his chief rival for a full gubernatorial term, Attorney General Lisa Madigan, to the Obama Senate seat. Blagojevich will talk tough, and Genson, a skilled ringmaster, will create as many sideshows as possible. But the smart money says that Rod Blagojevich, who held up Medicaid reimbursements to the state’s leading children’s hospital because the CEO wouldn’t give him a $50,000 campaign contribution, is headed for a long, long time away at taxpayer expense.

Scott Turow is a writer and attorney. He is the author of seven best-selling novels including Presumed Innocent, The Burden of Proof, and Personal Injuries. He frequently contributes essays and op-ed pieces to publications such as The New York Times, Washington Post, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, Playboy and The Atlantic.