DETROIT — The emergency manager for Flint, Michigan, appointed by Gov. Rick Snyder in 2012, rejected using the city’s river as drinking water after consulting with the state’s environmental protection agency.

Snyder appointed Ed Kurtz to be Flint’s second emergency manager and Kurtz selected Jerry Ambrose to be the city’s chief financial officer. Both men were tasked by the Republican governor’s administration with restructuring the city’s government to save money after it was in danger of becoming insolvent. One cost-saving measure considered was to quit buying municipal water from Detroit.

In a civil deposition not reported until now, Ambrose testified under oath that emergency manager Kurtz considered a proposal to use the Flint River, discussed the option with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, and then rejected it.

In 2014, Ambrose was deposed in a civil lawsuit brought by retired Flint municipal workers against the state over severe cuts to their health care benefits. Attorney Alec Gibbs questioned Ambrose about the water decision (a year before Flint learned it was being poisoned).

“There was brief evaluation of whether the city would be better off to simply use the Flint River as its primary source of water over the long term,” Ambrose said. “That was determined not to be feasible.”

“Who determined it wasn’t feasible?” Gibbs asked.

“It was a collective decision of the emergency management team based on conversations with the MDEQ that indicated they would not be supportive of the use of the Flint River on a long-term basis as a primary source of water,” Ambrose answered.

“What was the reason they gave?” Gibbs asked.

“You’ll have to ask them,” Ambrose said.

How could the river that was rejected as Flint’s permanent water source in December 2012 suddenly become suitable for consumption a mere 16 months later?

And who actually made the disastrous choice to start using the previously rejected river as the city’s temporary water source?

Howard Croft, the former director of public works for Flint who resigned in November 2015, asserted more than four months ago in a videotaped interview with the ACLU of Michigan that the decision to use the dangerously corrosive river came directly from the Snyder administration.

In the interview, Croft said that the decision to use the river was a financial one, with a review that “went up through the state.”

“All the way to the governor’s office?” the ACLU of Michigan asked him.

“All the way to the governor’s office,” Croft replied.

When questioned about Croft’s accusation in October, Sara Wurfel, Snyder’s spokeswoman at the time, offered up the false claim that the governor could not have made the decision to use the river because the city had been kicked off of Detroit’s system.

“The Detroit Water and Sewer Department at the time, back last spring, said, ‘Hey, we’re gonna cut you off.’”

This is a lie.

In a letter obtained by the ACLU of Michigan (PDF), emergency manager Darnell Earley wrote to DWSD in March 2014:

“Thank you for the correspondence [...] which provides Flint with the option of continuing to purchase water from DWSD… The City of Flint has actively pursued using the Flint River as a temporary water source… There will be no need for Flint to continue purchasing water to serve its residents and businesses after April 17, 2014.”

Snyder did not mention this letter in the history of the Flint water crisis that he presented in his State of the State address last week:

“First, the crisis began in spring 2013, when the Flint City Council voted 7-1 to buy water from Karegondi Water Authority [to be supplied by Lake Huron]. Former Flint Mayor Walling supported the move, and the Emergency Manager approved the plan. DWSD provided notice of termination to be effective one year later and, on April 25, 2014, Flint began using water from the Flint River as its interim source.”

Detroit did terminate a 50-year contract but it also diligently tried to strike a new deal to keep selling Flint clean, safe water. Earley rejected all offers and then sent that “thanks but no thanks” letter to Detroit saying that the decision had been made to use the Flint River.

If the governor really wants to come clean he needs to start telling the whole truth, not just convenient pieces of it.

Snyder tried to convince the public and the press he was doing that when he released emails from 2014 and 2015 (PDF). (There was rich symbolic irony in the fact that the first missive posted from the cache is completely redacted, blacked out from start to finish.)

If there was anything at all revelatory in the emails released so far, it is Snyder’s attention to detail.

There is, for example, a June 2015 email he sent out after being looped in on a positive television report about Michigan State Police bike patrols making their debut in Flint.

“Good work,” wrote the governor in a message sent to his team. “Let me know how things are going in our cities. Hopefully, we won’t have significant summer issues.”

As the world now knows, a slow-building scandal involving the lead contamination of the city’s water supply first came to light the following month, when a leaked U.S. Environmental Protection Agency memo sounding the alarm saw the light of day.

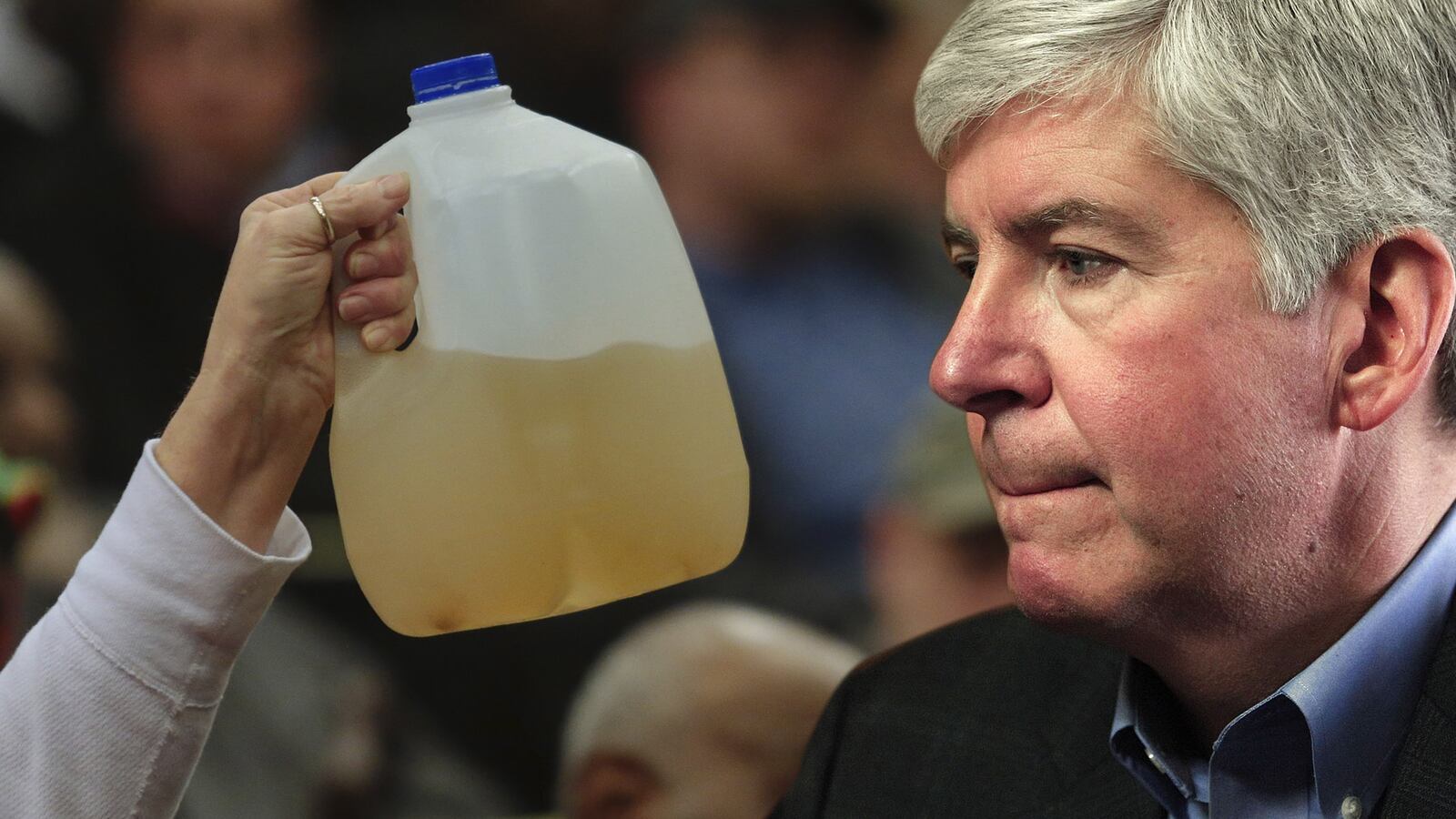

What remains still in the dark is the exact role Michigan’s detail-oriented governor played in subjecting the people of Flint to the hazards of a polluted river doubling as their municipal water supply. We also need to be clear on what the governor’s office and other state officials knew about the dangers posed by that river before the decision to use it was made.

Snyder can help shed light on that by releasing all of his emails—from both his government account and any personal email accounts that he might have used to conduct state business—going back to at least as early as the start of 2012 when members of his own administration considered and rejected using Flint’s river.

Given his willingness to release two years’ worth of emails, turning over documents from another two years should be no problem for a governor committed to transparency.

Curt Guyette is an investigative reporter for the ACLU of Michigan.