As a Utah man is executed in a hail of gunfire, Lawrence Schiller recalls his last talks with condemned man Gary Gilmore and what he witnessed as Gilmore chose to die by firing squad.

After 25 years on death row, Ronnie Lee Gardner was executed in Utah by a firing squad at 12:20 Friday morning, making him the first man put to death by firing squad in the United States in 14 years. The news brought back memories of conversations that writer Lawrence Schiller had with another killer, Gary Gilmore, in the last hours of his life. The Daily Beast asked Schiller to recount what it was like talking to a murderer just hours before his execution and witnessing the end of a life.

It was late at night, January 16, 1977, and I was huddled in the closet of my motel room in Orem, Utah. I’d pulled the phone in there with me and now I sat in the pitch dark and held the receiver close to my ear, the better to concentrate on my conversation with Gary Gilmore. It might be my last opportunity to question him, and there was something I still needed to know.

Click the Image to View a Gallery of Gary Gilmore's Final Days

Gilmore was due to be put to death the next day, after a long on-again, off-again struggle over his death sentence. Many groups were appealing it—everyone but Gilmore himself, that is. "I'd prefer to be shot," he'd told a judge, and, as was his right in Utah, he had chosen a firing squad to be his executioners.

• Big Fat Story: Behind Utah’s Firing SquadsI'd first read about Gilmore in the Los Angeles Examiner, after he was sentenced to death for murder and decided not to launch an appeal. Since the age of 14, Gilmore had lived mostly in reform schools and in prison. Then, in 1976, when he was 36, he was finally released to the custody of his cousin Brenda, only to kill two young men while he was searching for his missing girlfriend, Nicole Baker. When Gilmore first arrived in Provo after being released from prison, his cousin told him, "If you fuck up, I'll be the first to turn you in." True to her word, that’s what she did when he called her for help after killing the second young man.

• David Dow: Utah’s Gruesome Execution • Pia Ringheim Jensen reports from the prison I'd been in Utah chasing this story for months. The account in the Examiner had suggested to me that this man represented more than just himself. His story, and his choices, revealed a picture of America that rarely saw the light of day. I’d gotten to Gilmore by ingratiating myself with his lawyers and his family. By now, I had been interviewing him in person, sending him written questions, and talking to him on the phone for several months. In the end, I would interview over 100 people and would eventually ask Norman Mailer to write the story, which I was already a part of. The story would wind up offering a window not only on the issues involved in capital punishment but also onto the subculture of the region and the underbelly of America, as I called it then. Mailer's book, The Executioner’s Song, told the story as I reported and recounted it to him, and it would win the Pulitzer Prize in 1980.

But that night, sitting in the dark with a tape recorder hooked up to my phone, I felt Gilmore's part in the story hurtling toward its conclusion before I could grasp everything about it that I needed to know. I needed to understand more about his mother, Bessie Gilmore. Why hadn't she come to visit him? Why hadn't she tried to talk him into appealing? Why had she not tried to petition his sentence as so many others—strangers—were doing?

With Gilmore's execution only hours away, the prison authorities were allowing him to call almost anyone. He was free to talk now, but time was running out. I needed to focus, to feel as if we were in the same room. I needed to envision his face and to look into his eyes as we talked and I had chosen this spot, inside a dark closet, to dissolve the distance between us.

“Is there anything about your relationship with your mother or father,” I began, “that is so personal to you that, even at the moment of death, you'd rather not talk about it?”

“Goddamnit,” Gilmore replied. “I’m getting pissed off at that kind of question.... Man, my mother’s a hell of a woman.... She did the very goddamn best she could.... We always had something to eat, we always had somebody to tuck us in."

“You really love her, man, don’t you?” I said.

“Goddamnit, yes,” Gilmore said, his voice rising. “I don’t want to hear any fucking bullshit that she was mean to me. She never hit me.”

I let Gilmore talk. He told stories, some of which I had heard before. The conversation wandered for 10 more minutes. I was getting nowhere. Every time I raised a question about his mother, he changed the subject.

Gilmore’s body jerked, his chest rose outward, his head dropped down…. The smell from the guns was everywhere inside the abandoned cannery.

When I decided to press him one more time, he shouted, “You go down that road one more time, I’ll uninvite you to my execution.”

That time, I changed the subject. I could not let that happen.

At 1 a.m., a stay was issued by one court, then lifted at 7:35 a.m. by the Tenth Circuit Court. At 8:03 a.m., the Supreme Court of the United States denied a final appeal for a stay. Gilmore smiled and laughed when he was told: “It’s on.” The time had come. He would be executed. Gilmore had been partying all night in the prison’s visiting room, with family, friends, and prison guards, eating pizza and drinking from three small bottles of Jack Daniel’s, even playfully dancing with those in attendance. He was celebrating his execution, the first in the United States after 10 years. After deeming earlier death-penalty rulings unconstitutional, the court had now upheld another one.

It was cold, with snow on the ground, as I walked into an abandoned cannery behind the Utah State Prison in Draper, Utah. I had survived my argument with Gilmore, and, along with his Uncle Vern and his two attorneys, I was one of the guests he’d invited into his execution chamber.

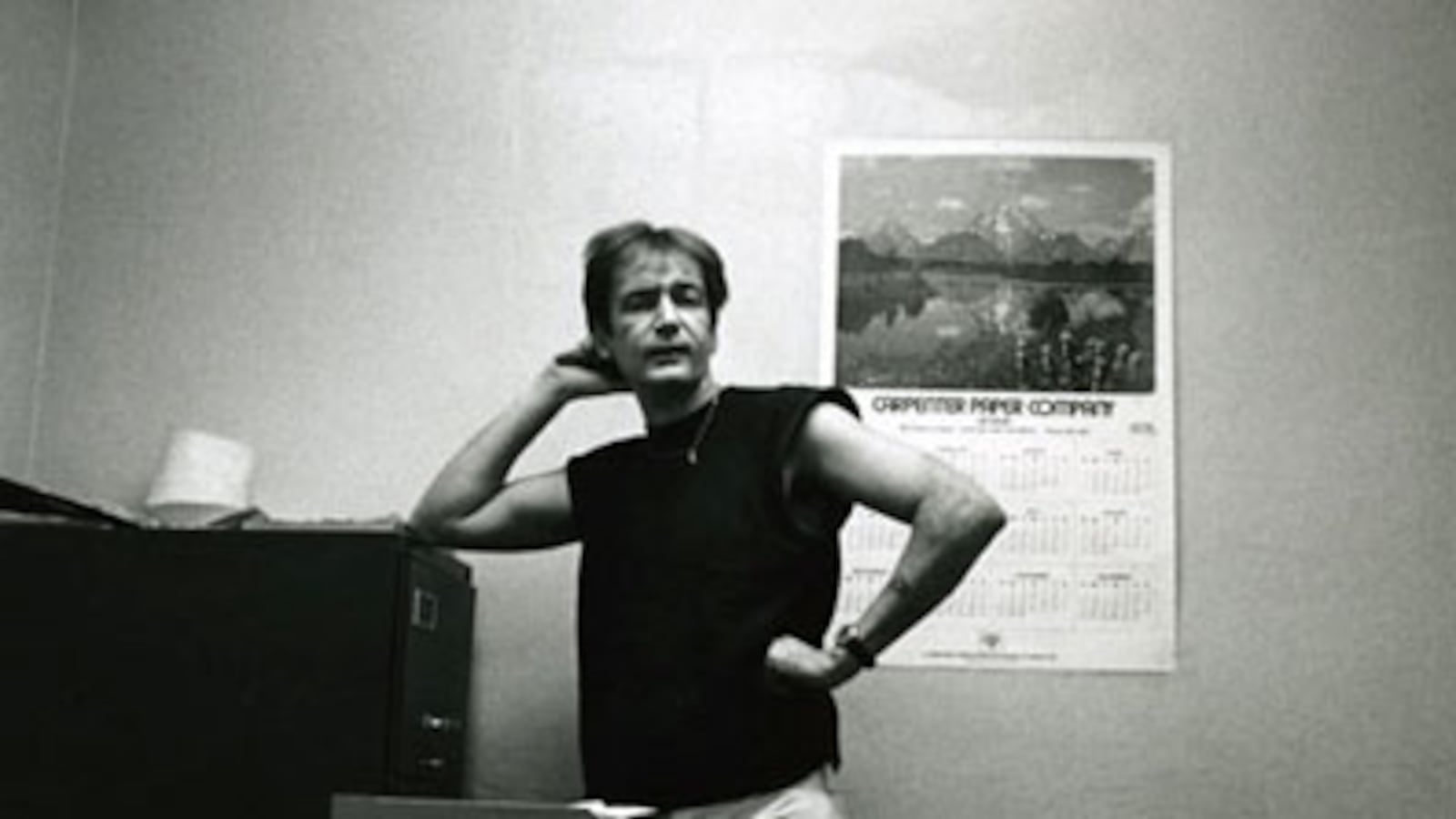

As I entered the one-room building, I saw some 20 people standing in the back, mostly prison officials in maroon jackets. Also at the back and off to the right, behind bright lights hanging from the ceiling, I saw a black blind with vertical cuts in the fabric. I was sure that the five police officers with rifles were concealed behind it. Opposite the blind and to my right was Gilmore, sitting on a wood platform, like on a stage, under a glare of lights. He sat on an old office chair, in a black sleeveless shirt, white pants, and tennis shoes. He had a smile on his face as he craned his neck to peek around the guards strapping him into the chair. He was peering at the black blind, trying to see the muzzles of the guns that would soon end his life. Behind him were a dirty mattress and rows of sandbags placed there to absorb the bullets. Gilmore chatted with the guards, making small talk, the smile never leaving his face. At one point he noticed me and I nodded back.

Now a guard approached the four of us. Gilmore wanted to say some last words to us, the guard said. We could each talk to him as he sat in his death chair. One by one, we walked some 30 feet, until we were within inches of him. His Uncle Vern pretended to thumb-wrestle with Gilmore, saying, “I could pull you right out of that chair if I wanted to.” I didn’t hear what Gilmore’s attorney Bob Moody said to him.

When it was my turn with him, he gave me a thin-lipped smile, like he was jeering. Without much thought, I said, “I don’t know what I’m here for.” He replied, “You’re going to help me escape.”

As I walked back and took my place next to Vern, his other attorney, Ron Stanger, approached Gilmore, squeezed his hand, and put an arm around his shoulder before moving back to join us. Shortly afterward, a series of events began, in coordinated fashion, which surely had been rehearsed.

With the precision of a parade master, Warden Sam Smith emerged and read the court order. All the while, Gilmore leaned as far to the left as he could, almost tipping over the chair he was strapped into. He was still looking for some sign of the gunmen behind the black fabric. After Smith finished reading, Gilmore smiled again, looked up toward the ceiling and then straight at the warden, and said, “Let’s do it!” Smith nodded.

Next to appear was Father Thomas Meersman. With a Bible in his hand, he gave Gilmore his last rites. At the end, Gilmore, speaking in Latin, said aloud, “Dominus vobiscum” (The Lord be with you), and Meersman replied, “Et cum spiritu tuo” (And with your spirit).

With almost military precision, Meersman walked away and another guard appeared. He placed a black hood over Gilmore’s head. Gilmore didn’t move or say a word. He accepted the darkness without giving any indication of what was going on in his mind.

Now more guards appeared and checked his leg and hand straps and his neck restraint. The prison doctor was there, too. He took a small piece of black fabric with a white circle painted on it and pinned it to Gilmore’s shirt, over his heart. Then Warden Smith approached us and handed us pieces of cotton to place in our ears. Without taking my eyes off Gilmore, who sat motionless and bathed in the bright lights, I began to insert some cotton into my right ear. At that moment, three or four shots rang out almost simultaneously, echoing throughout the cinder block building. Gilmore's body jerked, his chest rose outward, his head dropped down, though his neck was held by a heavily padded strap, and his right hand rose for a second before coming to rest on the chair’s arm. The smell from the guns was everywhere inside the abandoned cannery.

Then the doctor appeared, to check Gilmore’s heart with his stethoscope. He turned and shook his head, indicating that Gilmore was not dead yet. The room was still for maybe 15 or 20 seconds and then Warden Smith and Father Meersman joined the doctor. They loosened the strap around Gilmore's neck, allowing his body to fall forward while Smith checked the bullet's exit points on Gilmore’s back. That was when I saw blood dripping from under Gilmore’s white pants. It was pooling on the wood floor—a steady stream circling around his left shoe. Gilmore was dead. A few feet away from me, a guard said in a quiet voice, “It’s now time to leave.”

There’s no question that this had been rehearsed time and again, and it had all gone according to plan. Gilmore and the state of Utah, in partnership, had won. I didn’t understand then and still don’t understand what was accomplished. There haven’t been fewer murders.

In months after Gilmore's execution, the flood gates opened across the United States—one execution after another, hangings at first, and then lethal injections. It would be 20 years, almost to the day, before another prisoner would be executed by being shot in the heart. And now a firing squad will do it again. Where? In Utah, of course.

And as for Bessie Gilmore, after conducting 50 hours of interviews with her by phone and in person, Mailer and I concluded, reluctantly, that for some questions there are just no answers.

Lawrence Schiller began his career as a photojournalist for Life magazine and the Saturday Evening Post. He has published numerous books, including W. Eugene Smith's Minamata and Norman Mailer's Marilyn . He collaborated with Albert Goldman on Ladies and Gentleman , Lenny Bruce , and with Norman Mailer on The Executioner's Song and Oswald's Tale . He has also directed seven motion pictures and miniseries for television; The Executioner's Song and Peter the Great won five Emmys.