Just weeks after Facebook purged its own Black History Month ads by mistake, Women’s History Month ads are also being flagged and deleted.

Though the tech giant received media praise for its “refreshing” Black History Month content, it was one of dozens of advertisers that saw its ad campaigns about Black history removed from the social network in February. Among the others were a Fortune 500 energy company, the Chicago Bulls, the city government of Denver, a church, a grade school, health-care providers, a book store, universities, and history museums.

The cycle appears primed to start again, this time targeting Women’s History Month ads. Facebook eliminated a Feb. 26-Mar. 1 campaign on the women’s suffrage movement created by the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library. Promotions focusing on women from AmeriCorps, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, the Connecticut Office of Tourism, a New Zealand salmon brand, a tutoring company, and a historical museum have also been erased since the start of March.

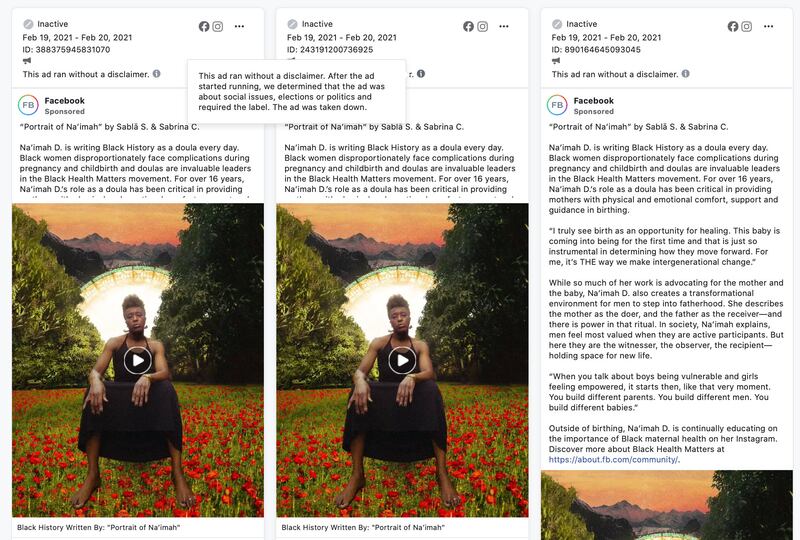

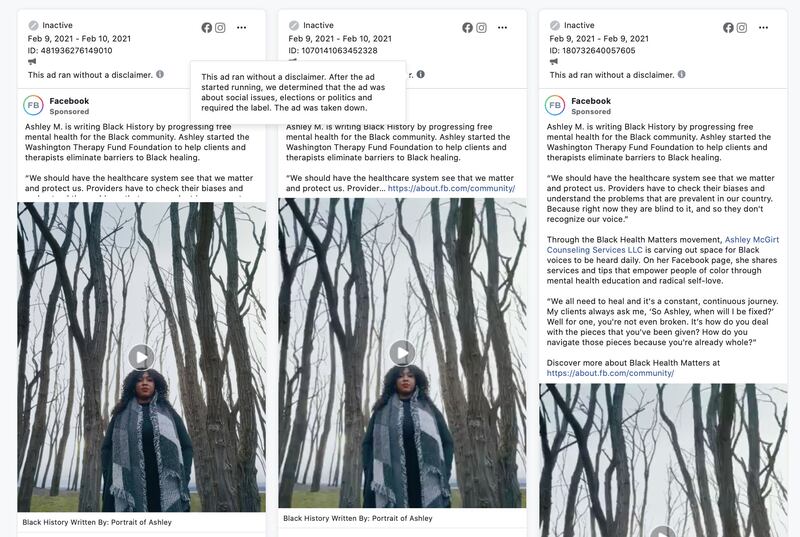

Facebook’s moderation system flagged and removed 14 “Facebook celebrates Black History Month” promotions run via the company’s main page, according to the Facebook Ad Library. The ads were axed for appearing without disclaimers noting they concerned “social issues, elections or politics.” All featured photos and videos of Black women speaking about their work and their lives—one as a therapist, others as skaters, another as a doula.

One of the deleted ads began, “Ashley M. is writing Black History by progressing free mental health for the Black community. Ashley started the Washington Therapy Fund Foundation to help clients and therapists eliminate barriers to Black healing.”

When contacted by The Daily Beast, Ashley McGirt, the analyst in the advertisement, did not know that some versions of the ads she appeared in had been flagged and pulled from the platform.

Another promotion showcased FroSkate, an organization that aims to encourage Black participation in skateboarding: “‘Skateboarding is typically a very white male-dominated space,’ explains Karlie T. ‘So when they see this Black girl on a skateboard flying past them, it’s shocking. There’s power in that.’”

Yet another axed ad appeared with what seems to be benign copy about Black leaders and their use of Facebook: “These movements have transformed into mantras for every generation. As we explore the stories that hero [sic] the beauty of natural hair and the bravery of natural leaders, we are inspired by the Black women who use their voices on our platforms to redefine the future.”

All the ads appeared above a link reading, “Facebook celebrates Black History Month” that led to about.fb.com/community, a page created by Facebook with the header: “Black history is written every day. People are using Facebook to connect and strengthen their communities.” The site touts Facebook’s fundraising and donation features and its support for small businesses.

It is unclear what elements of these advertisements triggered Facebook’s moderation systems or what about skateboarding, if anything, is political. The ads, which cost Facebook around $11,000, reached roughly 2.5 million people in total before they were taken down.

A spokesperson for Facebook told The Daily Beast that the takedowns of the company’s campaigns were a mistake and that the ads did not concern political issues, adding that Black History Month and Women’s History Month/International Women’s Day are not political matters under Facebook’s definition. To be designated an “issue” ad, a campaign must weigh in directly on legislation, an election, a petition, or a similar affair.

The spokesperson noted Facebook’s enforcement of the social issues policy and disclaimer is not perfect and that many Black History Month campaigns ran successfully, with many advertisers opting to preemptively use the disclaimer. The spokesperson emphasized that the phrases “Black history” and “women’s history” do not automatically put an ad up for moderator review.

Some of Facebook’s own ads were reinstated, but not all of them, according to the spokesperson. They will still show up in the Ad Library because of their original removal. Likewise, some of the Black History and Women’s History Month ads reappeared on the social network after the decisions to remove them were overturned, but not all.

Facebook’s review of ads is partly done by automated computer programs and partly by human content moderators. The company requires ads touching cultural third rails—“social issues, elections, or politics”—to appear with acknowledgments that the subject matter is sensitive. Ads with such labels require a higher standard of transparency and allow Facebook users to click through to see who paid for the ad and what demographics and regions the promotion targeted.

If an ad runs without such a disclaimer and Facebook’s post facto review determines the content does concern such material, it is taken down, and the advertiser is given the opportunity to resubmit the promotion.

The submission of Facebook’s ads without such labels implies that their creators believed the banners did not need them, that they thought the bulletins were not “about social issues, elections or politics.” It is unclear how or why Facebook’s own employees tripped over the advertising system designed by their company. Other versions of the same ads remain on Facebook’s main profile.

The removals echo a point Black activists have made for years—that simply existing while Black is politicized. In the case of the ads featuring a therapist and the doula, the featured women argue that Black people deserve to be healthy. Disparities between Black Americans and other racial groups, most starkly white people, have been well-documented for decades. Activists targeting medical inequalities have often taken up the Black Lives Matter banner as their own, tweaking the slogan to “Black Health Matters.”

If Facebook is axing its own Black History Month ads, other promotions on the same topic appear to run an even greater risk of removal. The term “Black history” alone seems to bring down the wrath of Facebook’s moderation.

Throughout the month of February, dozens of advertisers saw their Black History Month content removed from Facebook for appearing without “social issues” disclaimers, according to a Daily Beast review of the Ad Library. Denver’s city and county government ran ads from its verified profile honoring the city’s Black firefighters on Feb. 18. That ad was taken down. Insurer Blue Cross bought ads about “racial inequities in health care” that appeared from Feb. 28 to Mar. 1. Those were taken down. Southern Company Gas, a Fortune 500 power company that covers much of the American South, created multiple ads featuring Black employees that ran from Feb. 23 to Feb. 28. Those ads were removed for running without disclaimers as well.

A series of Chicago Bulls ads done in conjunction with Crown Royal and focused on “recognizing Black creatives” were cut from the platform. A campaign by Eagle’s Nest Church in Alpharetta, Georgia promoting a conversation with a Black pastor about Black History Month was also removed. Brown Physicians Inc., led by Brown University medical school faculty, saw ads about its own Black doctors taken down. Adventist Health, a hospital network, similarly had its ads about Black physicians in American history removed. The United Autoworkers Union purchased promotions about its first Black International Representative that were flagged. The University of Arizona ran a campaign from Feb. 19-Feb. 28 reading, “Our Black History is an anthem for a world that can be better.” The ad was removed for running without a disclaimer.

Trinity Christian Academy, a school in Addison, Texas, had its ads about teaching fourth graders Black history taken down. A group called Facing History and Ourselves, which describes itself as using “lessons of history to challenge teachers and their students to stand up to bigotry and hate,” bought ads promoting an event with Dr. Tommie Smith, who famously gave the Black power salute on the Olympic podium in 1968, that was cut. WSS, a Southern California clothing store, created a promotion with Puma that featured historically Black colleges; it too was removed.

A promotion by Santa Barbara Historical Museum on Mammy dolls was removed. Haymarket Books, a Chicago publisher, had its ads for a discount on books about Black activism removed. In January, the Chicago History Museum ran a campaign on its virtual programming on Martin Luther King Jr.’s impact that was taken down.

March has seen organizations create ads celebrating women and women’s history but encounter the same problems others did during Black History Month. Since the start of March, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, AmeriCorps, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, the Connecticut Office of Tourism, a New Zealand salmon brand, a tutoring company, and a historical museum have all run ads celebrating women's current and historical impact on various industries and areas of expertise only to see those campaigns removed by Facebook. None of the advertisements focused on existing legislation or elections.

The FDR library’s ad read, “Women’s History Month: A Conversation on Women’s Suffrage... From the convention at Seneca Falls to the passage of the 19th Amendment, the fight for equality laid the foundation for the work of Eleanor Roosevelt and the UDHR.”

Visit Connecticut’s ad read, “Connecticut is rich with stories of women who powerfully influenced American history—and March is the perfect time to honor them.”

And the Mormon church’s ad read, “We say thank you on this International Women’s Day to all women who lift and serve as Jesus Christ did.”

Facebook has made similar blunders before. In 2018, the company removed ads that contained the words “Black,” “African-American,” “Hispanic,” or “LGBT” for running without political disclosures despite containing no political point of view. In 2019, The Daily Beast reported that the social network had repeatedly disabled ads from hospitals and state health departments about vaccines but allowed paid bulletins from anti-vaccine conspiracy theorists.