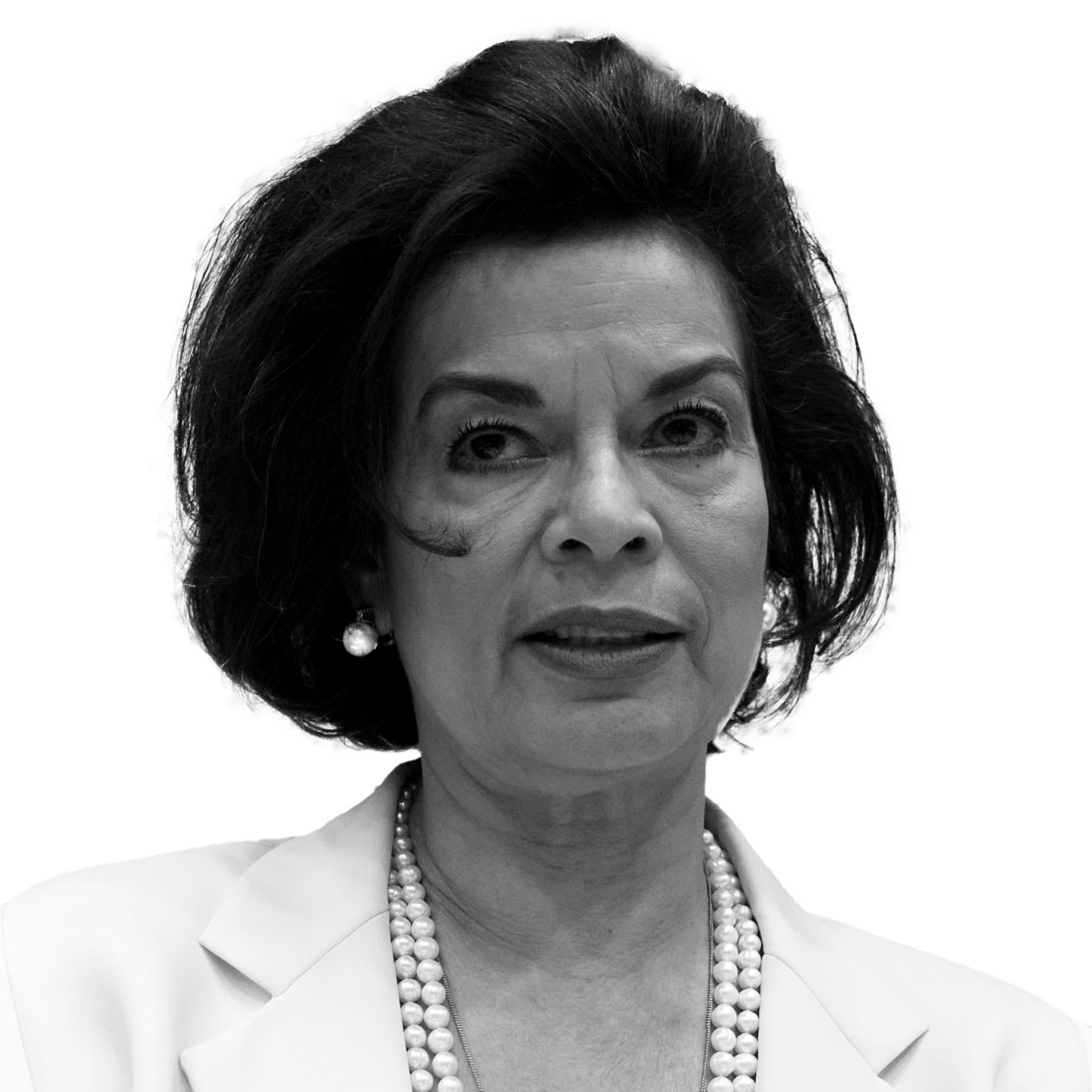

Bianca Jagger is on the phone from Nicaragua. Over the past two weeks she has campaigned for human rights in her native country, and borne witness to mounting violence as the regime uses murder to hold on to power. We had talked several times over several days, but now, as she spoke about students she had met with, and who had been shot down, she choked back tears.

Over the last two months, largely unnoticed by the rest of the world, unrest in Nicaragua has grown into a nationwide uprising that has fought to remain peaceful. What began in mid-April after a violent crackdown on protests about pension reforms has continued to gain popular support, and to be met with increasing brutality and deadly force, especially by the paramilitary gangs known as “shock forces” or turbas.

Human rights groups have recorded more than 140 deaths, more than 1000 injured, and counting. Families search for relatives, especially young people, taken violently on the street and disappeared into the country’s prisons—or disappeared altogether. Bianca, representing the Bianca Jagger Human Rights Foundation, participated in a press conference where Amnesty International presented its investigation of the violence. The title summed up the government’s policy in three words: “Shoot To Kill.”

The regime of Daniel Ortega has shown it will stop at nothing to crush the opposition. Yet the spirit of the opposition will not be crushed. “The students are exhausted,” Bianca said, sounding exhausted herself. “They are worn out. They are drained. And they are aware of how much in danger they are. How threatened they are. Their courage and determination to achieve justice and democracy and free elections is astonishing given the horror they are facing.”

As we talk, I am in something of a time warp. Bianca Jagger and I have known each other for almost 40 years, having met in Nicaragua when the Sandinista revolution still seemed like it might be something to celebrate. She was a passionate defender of human rights and democracy even then, although best known in those days as a beautiful actress who had married a rock star.

In this uprising there are so many echoes of the past, so many images from the old days. For the young men and women at the barricades today, even the smells must be much the same as they were during the uprisings 40 years ago—the lacerating fumes of tear gas, the dust of cinder block barriers, and the sweat dripping off young men and women waiting under the hot Central American sun for the inevitable attacks on their thrown-together redoubts. They are far too young to remember first hand. But what they do know is that one aging, corrupt leader of that old revolt has become the savage enemy of this one.

Another key difference: These protests are non-violent. It’s the government that’s doing the killing, not the kids who’ve cordoned off their colleges and set up scores of roadblocks on the nation’s highways. In some contested areas people carry makeshift “mortars,” but not guns. “They are determined to have nonviolent resistance,” says Bianca. “When people have shown up with weapons they have sent them away. Nobody in the uprising wants ‘armed struggle’ in Nicaragua.”

But despite efforts by the Catholic Church and others to mediate, the government response remains ferocious, and in the world of 2018, as we know all too well by now, this is the way horrible disasters start. In recent memory, we saw the inspiring enthusiasm of the young people who thought they could overthrow the dynastic “revolutionary” regime in Syria in 2011. But they were met with gruesome repression as the leader preferred to drag his country into the maelstrom of civil war rather than surrender his dictatorship.

A paradigm closer on the map and much closer in culture is Venezuela, where the regime of Nicolás Maduro faced massive protests in recent years, and wore them down, and tore the opposition apart, then did the same to the whole political system of his country until he could guarantee his own re-election. The suffering of his people be damned; he has survived. At least for now.

All that said, Nicaragua is its own place, and it may yet surprise us. The problem there is focused very clearly on two people at the top, former Sandinista commander and junta member, and now president, Daniel Ortega, and his wife Rosario Murillo. And, realistically, at this point the solution must not be to compromise with their rule but to end it.

On Monday two weeks ago, Bianca and Erika Guevara-Rosas of Amnesty International visited the Jesuit university in Managua, the UCA (Universidad Centroamericana de Nicaragua). They wanted to meet its rector, José Alberto Idiáquez, known as Father Chepe, who has received numerous death threats.

Just a few days earlier at a little before 1 a.m. on May 27 two Hilux pickup trucks, the preferred vehicles of the turbas, pulled up in front of the main entrance. Hooded men in the back of one of them shot a one-pound mortar at the two guards. They missed, but not for want of trying. Father Chepe denounced the attack and declared, “The UCA, faithful to its Christian principles, will continue demanding what our people demand: justice for the dozens of people murdered in the massacre of April that continues in May.”

Again, there are terrible echoes of Central America’s past, including the murders in El Salvador of Archbishop Oscar Romero in 1980, and of the Jesuit educators at the university in San Salvador in 1989. But, then, the death squads served the interests of the fascist right wing. In Nicaragua, they serve Ortega and Murillo.

Pope Francis, a Jesuit who has vivid memories of the repression in his native Argentina, spoke out publicly, condemning the “serious violence" in Nicaragua "carried out by armed groups to repress social protests.”

One of the most powerful voices for the people has been Silvio José Baéz, the auxiliary bishop of Managua, a “heroic priest,” says Bianca, who has been the object of many death threats himself.

The church was instrumental pressuring Ortega to allow a mission by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to visit Nicaragua on a fact-finding tour in mid-May.

Ortega had claimed that people killed in the protests were “murderers.” Murillo accused them of “fabricating deaths” and acting “like vampires hungry for blood to feed their personal agendas.”

That is not what the human rights commission found: “Dozens of persons killed and hundreds wounded; illegal and arbitrary detentions; practices of torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment; censorship and attacks on the press; and other forms of intimidation such as threats, harassment and persecution, all aimed at dissolving the protests and inhibiting citizen participation.”

As Bianca and Guevara-Rosas talked in Father Chepe’s office, “we suddenly heard shots and mortars outside,” Bianca told me. Guevara-Rosas remembers “the terrible thunder of gunfire was relentless.” The action was at the engineering university across the street from the UCA. It was under attack by the turbas. As Bianca watched from the street, crowds rushed to the scene to try to stop the attackers. Then the anti-riot police arrived in force, some of them with AK-47 assault rifles. “They came on as if they were going to war,” Bianca remembered. By that evening, the staff at Bautista hospital said they treated 41 young people, one of whom died from a chest wound.

The next day, Amnesty together with the Bianca Jagger Human Rights Foundation officially presented the 36-page report, “Shoot to Kill: Nicaragua’s Strategy to Repress Protest” (PDF), and Bianca spoke at the press conference. She started by pleading with Ortega to stop killing the students, the journalists, the workers. “What we have here is a dirty war,” she said, using a phrase that evoked the gruesome right-wing repression in Latin America in the 1970s. She said Ortega’s minions are killing young people “like dogs” and called on them to stop.

Tensions were building in anticipation of the march called for May 30, Mother’s Day in Nicaragua, when the mothers of scores of young people who’d been slain would be at the heart of the procession.

Huge crowds poured into the streets of Managua and other cities. “There were hundreds of thousands of people with Nicaraguan flags,” Bianca told me, and many reports confirmed the phenomenal scale of the demonstration.

Just before it began, Bianca visited students at Nicaragua’s national university, then spoke with Christiane Amanpour on CNN, who asked if she was afraid. And yes, she said, she was.

“On Twitter there are some calls to attack the mothers and all of those who will participate in the march,” she said. “So when I go out I am wondering what will happen. What will happen to them? What may happen to me? I don’t know. I hope that God is with us and that I will come back and be able to talk to you again.

“People who say they are not afraid, they are foolish,” said Bianca. “I know the risks. I am here because I think that my voice is important. I am here because I feel about each of these kids as if they were my kids or maybe my grandchildren. As a mother. And because… I can’t fathom that little children—because they are children, some are 15—have been killed. And that they are prepared to be killed. They are prepared to sacrifice themselves. I have met with them. And they say to me, ‘You know, we think we are dead. Every minute that we live we are living on borrowed time.’”

Later, on the phone from Managua, Bianca told me, “Everybody thought that Ortega and Murillo couldn’t attack the march because it was a peaceful march on Mother’s Day.” There were the mothers who had lost their children; and many more mothers who could imagine losing their children. Bianca walked with a walking stick, as she does these days. “People came to me and said, ‘Don’t leave us.’” She moved toward the forward ranks of the demonstration, not to the front, but the second rank of mothers. And then the shooting began. “Some of the people got me out of there,” she said. By the end of the day, 16 more people had been killed, apparently by snipers, and 70 or 80 injured.

Ortega first came to power as part of the collective Sandinista leadership after battles had been fought by rag-tag muchachos in many of the same cities and towns that have seen uprisings in the last few weeks: Masaya, Estelí, Monimbo, and of course Managua. On July 19, 1979, at last, the Sandinistas overthrew the Somoza family dictatorship that had been installed by the American Marines half a century before.

In the early 1980s, many people had high hopes the Nicaraguan revolution would find a path forward to democracy for the impoverished peoples of Central America. (Even Henry Kissinger acknowledged some sort of revolution was needed.) Volunteers from Europe and the Americas, including the United States, poured into the country to help. And many on the left saw the Sandinistas as heroes, especially as they faced the calculated wrath of the right-wing Reagan administration, which mined Nicaragua’s harbors and underwrote a brutal covert war by rebels known as “Contras.” Resolutely, and with increasing brutality of its own, the Sandinista regime survived and Ortega maneuvered himself into the presidency. Then, in 1990, when the Soviet Union was collapsing and had no need for clients in Central America, Ortega was defeated in national elections and chose to step down peacefully.

After many long years in opposition, and two failed bids to retake the presidency, Ortega and his disciplined party made a comeback in 2007. Corruption scandals had shaken the interim administrations to their foundations. Indeed, Arnoldo Alemán, president from 1997 to 2002, was named by Transparency International as one of the 10 most corrupt leaders in the world.

In the years since their return, Ortega and Murillo, who is his vice president as well as his spouse, have cut extraordinary political deals to insure their survival. “I know Daniel Ortega very well,” Bianca told CNN last month. “When he came back to power he was perverse. He was corrupt. He made deals with the most corrupt segments of society.”

Ortega stacked the courts and reinterpreted the constitution to allow him to keep his post as president, potentially, for life. (His control over the judiciary also helped protect Ortega from accusations by his stepdaughter, Murillo’s child, that he had sexually abused her for many years, starting when she was 11 years old.) He also bought up almost all the press outlets in the country, and since the unrest began, the few independent voices have come under direct attack. An independent radio station was torched. A reporter was shot and killed on Facebook live.

Over time, Ortega and Murillo have shown there is no one they will not embrace—or betray—to hold on to power. Thus their courts reversed former President Alemán’s 20-year sentence for corruption in an apparent trade-off for conservative votes in Nicaragua’s National Assembly. Ortega and Murillo helped the rich get richer, cementing support from the private sector. These so-called Marxist-Leninist atheists professed their Catholic faith and won the support of the conservative Cardinal Miguel Obando y Bravo by banning all abortions, including those that endanger the mother’s life. (Obando y Bravo died on June 4 this year after several years in retirement.) When Ortega and Murillo met resistance they set out to intimidate and crush protest movements by using the police and the turbas.

“Ortega is a liar, a hypocrite,” Bianca told CNN. He has given himself control over all the powers of coercion—the military, the police, the riot police, the mob—while he has dismantled all legal institutions that might be an obstacle to his total control of the country.

As Univision News wrote succinctly last year, Ortega is “a wily politico who has made a career out of hatching secretive pacts with opponents, then devouring them alive.” And a major concern among Nicaraguans last year was that Organization of American States Secretary General Luis Almagro, in secretive talks with Ortega, would allow the Nicaragua strongman to buy time, and eventually stay in power. In fact, Almagro legitimized Ortega’s completely illegitimate election to a third consecutive term. OAS representatives have been back in Managua in recent days, and many fear they’re going to buy Ortega still more time to do more killing.

The devastating report by the human rights commission might not prevent that, but when it presents its full findings to the OAS, few doubts will remain about the evil of the Ortega regime.

Nicaragua’s population is a little over 6 million, about the size of Maryland’s, with few natural sources and a tiny economy. But Ortega, now 72, always hoped to project himself on the world stage as his generation’s version of Fidel Castro, and he has remained a committed third-worlder hobnobbing with leaders despised by Washington.

In the early days of the Sandinista regime, Ortega embraced the PLO’s Yasser Arafat and Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi. After Ortega’s return to power in 2007, one of his first trips abroad was to Tehran to meet with Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who declared that nothing could separate the two countries, which were united to face common enemies. The revolutions of Iran and Nicaragua, born at the same time in the late 1970s, “are almost twins,” Ortega declared.

But Ortega’s greatest international ally was Venezuela’s late strongman Hugo Chávez, who shared his country’s vast oil riches generously with little Nicaragua. Indeed, Ortega hosted Chávez, along with Ahmadinejad, at his second consecutive inauguration in 2012. At that event Ortega also lamented the death of Gaddafi, and reportedly offered “a brief valediction to Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein.”

Ortega has sought support from Russia’s Vladimir Putin, who paid a brief visit in 2014, and has cultivated ties with Beijing. A few years ago, Nicaragua announced grandiose and improbable plans with a mysterious Chinese financier to build a canal through the center of the country. The project may never be completed, but it gave a pretext to the Ortega regime to seize vast tracts of land by eminent domain, and continues to pose enormous risks to the environment well beyond Nicaragua’s borders. Bianca has called it, with reason, an “environmental crime.”

Despite all this, there’s barely been a ripple in Washington. Where once Nicaragua was the center of world attention thanks to the hostile spotlight put on it by the Reagan administration, its travails now attract little notice from North American media.

“Why is Nicaragua not the center of attention? Students are being killed!” Bianca asked CNN’s Christiane Amanpour, who had no real answer.

Perhaps the media are waiting for Trump to tweet something about what’s going on. And perhaps, when his grotesque feud with the G6 and the circus in Singapore subside, that day will not be so far away.

On Thursday, the U.S. State Department made an interesting announcement: “The political violence by police and pro-government thugs against the people of Nicaragua, particularly university students, shows a blatant disregard for human rights and is unacceptable.” So visa restrictions are being placed on “National Police officials, municipal government officials, and a Ministry of Health official—specifically those directing or overseeing violence against others exercising their rights of peaceful assembly and freedom of expression, thereby undermining Nicaragua’s democracy. These officials have operated with impunity across the country, including in Managua, León, Estelí, and Matagalpa. In certain circumstances, family members of those individuals will also be subject to visa restrictions.” The communiqué did not name names, but the State Department’s targets presumably know who they are.

Meanwhile, the roadblocks and barricades called tranques continue to be thrown up on main roads all over the country. On Wednesday there were at least 40 described by the local press as “permanent,” meaning they stopped all traffic but emergency vehicles, and another 18 or so that allowed staggered passage for traffic, say, once an hour.

On Thursday evening last week, the Catholic bishops of Nicaragua asked to meet with Ortega, to see if they would renew the dialogue that they broke off in May. The goal back then, said Auxiliary Bishop Silvio José Baéz, “was to pave the way for the democratization of Nicaragua.” But that was not happening and the violence was growing worse. This time around, the bishops did not say that they demanded Ortega step down, but they came very close, demanding that new elections be held on an accelerated timetable:

“We have raised to the President the pain and anguish of the people in the face of the violence suffered in recent weeks,” Cardinal Leopoldo Brenes said in a statement. “We have delivered the proposal that reflects the feelings of many sectors of Nicaraguan society and expresses the desire of the vast majority of the population. We await his written response as soon as possible.” They gave Ortega two days “to reflect.”

That same night, Bianca talked again with the exhausted students protesting at the national university who told her they would persevere no matter what.

A few hours later, another Hilux pickup truck rolled up in front of their barricade and opened fire. Two were injured. One was killed.

“That was Ortega’s answer,” said Bianca.