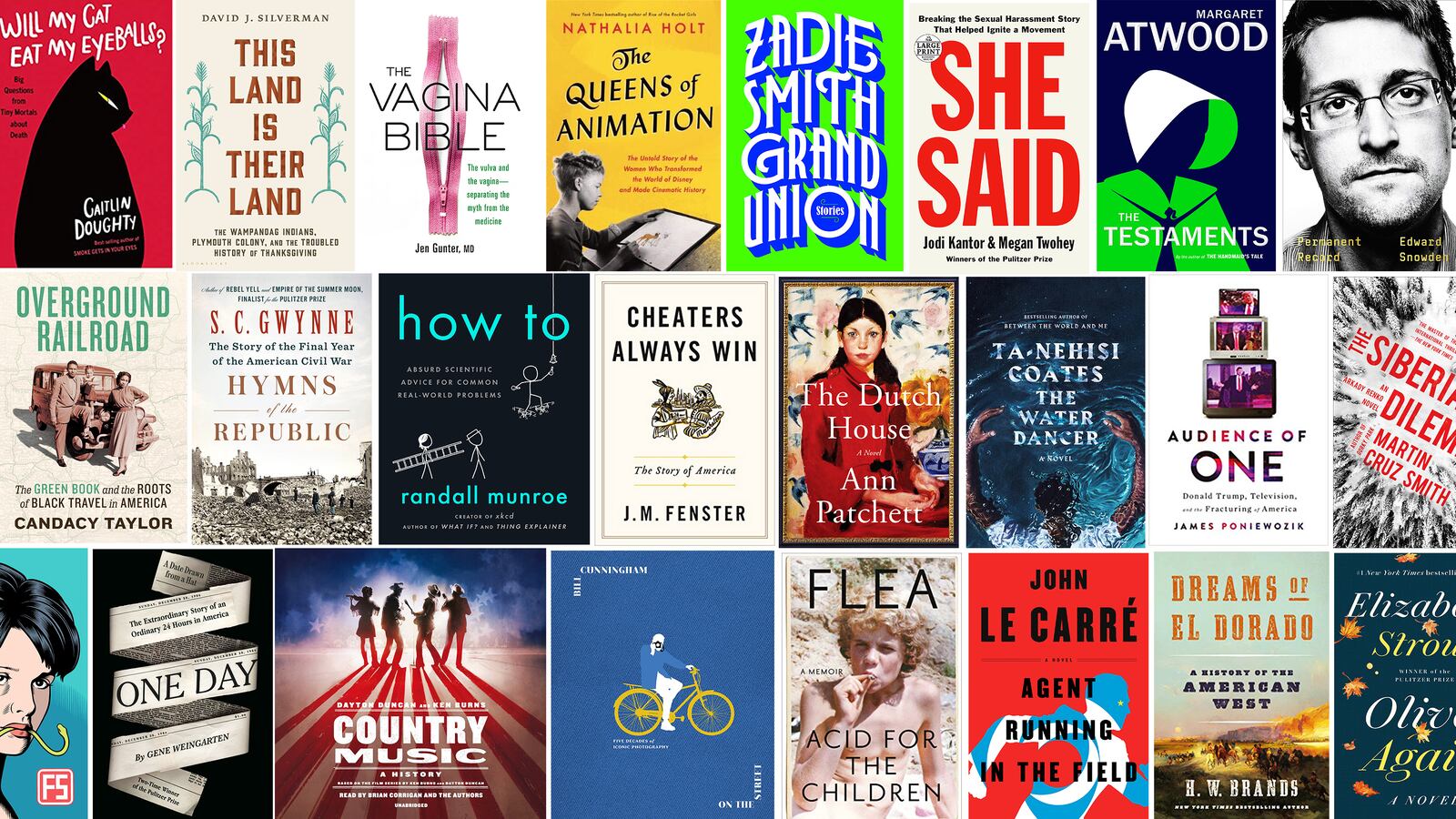

A sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale. A Sequel to Olive Kitteridge. The return of Arkady Renko. Salman Rushdie rewrites Don Quixote. Call it the season of retreads if you must. We call it many happy returns to best loved characters. And that’s just in the listings for fall fiction. Between now and Christmas, we’ll also see a memoir from Edward Snowden, a new book on the Civil War from historian S.C. Gwynne, the backstory of the Harvey Weinstein saga from two reporters responsible for breaking much of that saga, and shrewdly revisionist takes on cheating and Thanksgiving. As far as books are concerned, we’re calling this Fall Fully-Loaded.

Audience of One: Donald Trump, Television, and the Fracturing of America by James Poniewozik. Liveright, Sept. 10.

Say what you will about the old days when the three major networks dominated television, but at least then everyone was more or less on the same page. Then all we had to complain about was blandness and the way the networks insulted their viewers’ intelligence at every turn. Now, in the era of “a channel for everyone,” we’re siloed into our particular echo chambers, and your neighbor has a totally different set of reference points. The Tower of Babel never really goes out of fashion as a metaphor. Tracing the evolution of TV from three channels to three zillion, the astute New York Times TV critic explains how we have arrived at the so-called Golden Age of Television and why that so precisely overlaps with the Age of Trump.

Country Music: An Illustrated History by Dayton Duncan and Ken Burns. Knopf, Sept. 10.

Every major Ken Burns documentary gets its accompanying coffee-table book (Follow along at home!). But while the crucial ingredient of the latest Burns effort, i.e., music, is missing here, let’s face it: the “look” of country is almost as important as the music (and, lately, maybe more important). Cowboy hats. Those poofy square dance skirts. Nudie suits. Guitars dripping with mother-of-pearl inlay. Swimming pools shaped like guitars. So an illustrated history of country music is nothing to sneer at, especially when the text is written by Burns and his longtime collaborator Dayton Duncan. The book is like the eight-part doc that debuts Sept. 17 on PBS: scrupulously comprehensive and occasionally inspired; a good introduction to a subject that needs a good introduction.

Permanent Record by Edward Snowden. Metropolitan Books, Sept. 17.

His publisher is letting no one near this book until it comes out in mid-September, and they swear it’s not a policy book or really a book about public affairs at all. Instead, it’s being billed as a memoir, the story of how Snowden grew up to become the sort of man who kept secrets and then made those secrets public. For that he’s been called a hero and a traitor. Snowden forces people to take sides. And he’s complicated in ways that can trouble even his defenders, as with his at best lukewarm criticism of Putin’s authoritarianism, not to mention the fact that his asylum in Russia gives Putin cover as an almost principled leader. But for all his fame or infamy, Snowden remains more cipher than man. Love him or hate him, but you can’t say you know much about him or what makes him tick. Here’s probably your best chance to find out.

The Queens of Animation: The Untold Story of the Women Who Transformed the World of Disney and Made Cinematic History by Nathalia Holt. Little, Brown, Sept. 17.

Author of Rise of the Rocket Girls, Holt recounts how women worked their way into and held their own in Disney’s boys’-club animation departments.

Let’s face facts: women understand wickedness and purity, stepmothers and princesses better than men. It’s all in a day’s overcoming and achieving! Stories of leaving an insufferable castle for a new empty castle—albeit with a prince installed—are at the heart of Disney’s Princess oeuvre. Behind the scenes, however, women were all but erased from the creative process at Disney. Sylvia Holland and Bianca Majolie were two exceptions. Both worked as storyboard artists on Fantasia and suffered inside a male-dominated industry at a time when few women worked outside the house. The subjects in The Queens of Animation mostly passed away without ever seeing their names in the credits. Diaries, memos, interviews with family members and some Disney archives color in the lives of women contributors who were hired to ink the characters that are icons of Americana. It was a long, hard road from Fantasia to Frozen, the only feature-length Disney film to be directed by a woman.

She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey. Penguin Press, Oct. 1.

Pulitzer Prize-winning reporters Kantor and Twohey give us the backstory of how they uncovered Harvey Weinstein’s sexual misconduct, the bombshell case that helped ignite the #MeToo movement and made Kantor and Twohey this century’s Bernstein and Woodward. The balance of power in the workplace can be tipped by men in a number of ways, but none more sinister than sexual predation by a person who can make or break careers. Only so much insight can be shed in The New York Times to illuminate three decades of payouts and a culture of silence. This book expands the story, offering a broader account of the reporters’ findings, insight into their investigation, and the aftermath.

Edison by Edmund Morris. Random House, Oct. 22.

After seven years sifting through five million pages of archives, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Morris has left us this biography as his last act—Morris died of a stroke in May at the age of 78. But what a finale. Sure, door-stop sized biographies are the noxious norm these days, but if anyone deserves a long look at a long life, it’s Thomas Alva Edison. He’d be famous for the invention of the electric light bulb and the phonograph, but Edison took out 1,093 patents in the U.S. alone, and once dreamed up 112 inventions in a single day. Explaining this complicated, visionary eccentric (he lived almost exclusively on seven pints of milk and a quarter of an orange a day for the last years of his life) is a herculean task, but Morris pulls it off with the same elan he displayed with his multi-volume bio of Teddy Roosevelt.

One Day: The Extraordinary Story of an Ordinary 24 Hours in America by Gene Weingarten. Blue Rider, Oct. 22.

Six years ago, Pulitzer-winner Weingarten asked three strangers to select a date at random. They picked Dec. 28, 1986, a Sunday. Then Weingarten went to work, digging and digging to find out everything he could about what happened on that day in what we usually think of as the deadest week of the year. The stories he turned up were sad, happy, funny, tragic, and everything in between. The only thing the stories had in common was that they demolished the very idea of normal and everyday: in Weingarten’s cosmos, there is no such thing. This snapshot of the nation on one particular day is one that deserves pride of place in America’s family album.

Dreams of El Dorado: A History of the American West by H.W. Brands. Basic, Oct. 22.

We are constantly rewriting the history of the American West. No longer, for example, do we speak of the settling of the West, since for significant, non-white populations, unsettled would be the more appropriate word. Brands, the kind of writer who gives the title “popular historian” a good name, manages to give all his protagonists—from Lewis & Clark to Geronimo to John Muir—sufficient respect while still managing to tell a host of rousing stories about the Gold Rush, the Indian wars, and cattle drives. As his title implies, this is not a story about destiny, manifest or any other kind; it’s a story about dreaming and desire and, too often, destruction.

Palm Beach, Mar-a-Lago, and the Rise of America’s Xanadu by Les Standiford. Atlantic Monthly Press, Nov. 5.

Between them, railroad magnates Henry Plant and Henry Flagler divvied up the early development of Florida, with Plant working the Gulf Coast and Flagler dominating the Atlantic side. If you had to pick a winner, it would be Flagler, probably because he had the better beach. Long term: both were winners, because in Florida, the developers always win. But Flagler certainly knew how to attract a more noteworthy clientele. The rich people who rode his trains and inhabited the faux Mediterranean mansions cooked up by Paris Singer and Addison Mizner in the early 20th century weren’t much different from aspirational wannabes like Donald Trump, whose Mar-A-Lago once housed Marjorie Meriwether Post, the doyenne of Palm Beach high society, when there was still a high society to rule. Now it’s just pink buildings, billionaires, and little people with more money than sense.

Hymns of the Republic: The Story of the Final Year of the American Civil War by S.C. Gwynne. Scribner, Oct. 29.

The acclaimed author of Empire of the Summer Moon and Rebel Yell drills down on the agonizingly slow, murderous crawl that was the last year of the Civil War. At this point in the conflict, all thoughts of the romance of war had been washed away by rivers of blood, leaving the players—Grant, Lee, Sherman, Lincoln, and, surprisingly but fittingly, Clara Barton—exposed and etched like the figures in a Greek tragedy.

This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving by David J. Silverman. Bloomsbury, Nov. 5.

That fun story about Squanto fertilizing crops with dead fish to help the poor starving Pilgrims is rubbish. In 1620, after England finally washed its hands of religious fanatics, the Pilgrims became the Natives’ problem. For a hot second, there was an arms-for-food agreement—the Pilgrims knew nothing of this New England they were settling. The Wampanoag came in peace so they could defend themselves against their Indian foes with shiny modern weapons. But the Natives didn’t have the immunities to fend off the diseases the Pilgrims dumped on the shores of Massachusetts. Indians dropped like flies, lending instant credence to the manifest destiny idea. And the English tromped through the new colony as Native Americans died in their wake. Yes, there was a feast of thanks for the bounty in 1621. But it was more a “thanks but no thanks” in retrospect. And Squanto didn’t factor in, because he had been enslaved and shipped to Europe, which is why he spoke killer English.

Acid for the Children: A Memoir by Flea. Grand Central Publishing, Nov. 5.

Most punk rockers have a name and a punchline for a last name (Lee Ving, Pat Smear, Lorna Doom). Flea needs only one. He is set apart by a healthy list of other things: most notably playing bass super well (understatement), co-founding the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Silverlake Music Conservatory, and movie acting (not to mention his million and one appearances in documentaries about punk). And now he proves to be an enchanting writer, all those years on the road having made a bibliophile out of this quiet, sensitive man with a gift with words. He was born Michael Balzary in Australia, his early life took a confusing turn when the family moved to Westchester County, New York, where he lived in a fairly conservative home until his parents divorced and he and his sister ended up in Los Angeles with their mother and her jazz musician boyfriend (before he found punk, young Flea was a jazz fanatic). From there he would go on to drugs, parties, and a band known for antics both on and off stage. But music anchored him. Somehow that sweet boy with angelic blond curls found his way and pays it forward.

Cheaters Always Win: The Story of America by J.M. Fenster. Twelve, Dec. 3.

J.M. Fenster holds a mirror up to Americans in her thoroughly entertaining charting of historical moments where cheating won the day. In all of us, a low-key or brazen cheater lurks. From the banal marital affair to cutthroat political backbiting, Cheaters Always Win spotlights America’s can't-quit-you-baby relationship with deception. Wickedly fascinating accounts detail how America came to accept cheating as a resource for getting ahead, getting what you want, and using it to get more. (And how our ethics were stretched by western expansion into a twisted idea of fairness.) Even with charities, Americans get away with what they can.

Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America by Candacy Taylor, Abrams, Jan. 7.

During Jim Crow, the back of the bus was how it was for many Americans on holiday—black travelers had to seek out separate hotels, restaurants, beauty parlors, and barber shops. Even finding a bathroom could be perilous—and not just in the South—well into the 20th Century. From 1936-66, Victor Green, a Harlem postal worker, published The Negro Traveler’s Green Book, a directory of addresses and phone numbers for black-friendly establishments where African Americans would be welcomed and safe while on the road. The overarching story of the Green Book reminds us that individual acts of bravery contributed immeasurably to standing up to segregation.

The Vagina Bible by Jen Gunter. Citadel. Aug. 27.

This is a fun—and useful—addition to every bookshelf or bedside table: a basic owner’s manual for the care and maintenance of our vaginas from OB-GYN and New York Times columnist Jen Gunter. The Vagina Bible begins with a diagram and basic terminology. In short, everything touching the underwear is vulva; the inner workings compose the vagina. From there, things just get more intriguing, sometimes laughably so: Most female junk is named for men, e.g., Gabriele Falloppio and the fallopian tubes—sounds like a band! Thanks to MRI technology, the function and structure of the clitoris have now been revealed: A mindblowing four components make up the clitoris, and most of it can’t be seen. And, turns out, it is the only part of the human body built entirely for pleasure, and capable of multiple orgasms. Bye-bye, “miniature penis” myth.

How To: Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems by Randall Munroe. Riverhead, Sept. 3.

How To is downright ridiculous in the best ways. From Randall Munroe—a NASA roboticist and author of What If and the webcomic XKCD—come the most difficult solutions to everyday problems, replete with supporting footnotes and equations. If you want to throw a pool party, the first order of business is building a pool. The most efficient way to send a large data file to a friend in the mountains in Mexico? Encode the information into the DNA of butterflies. All the data contained in the internet can be transferred that way. Otherwise, it’s millions and millions of suitcases full of SD cards, and that’s just silly. The kicker is, Munroe’s loony but logical-to-a-fault solutions actually work. If you want to find the best way to go around your elbow to get to your thumb, he can tell you precisely how to overthink that.

Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs: Big Questions From Tiny Mortals About Death by Caitlin Doughty. Norton, Sept. 10.

Call her Lady MacDeath, or the funerary Miss Manners. Mortician, funeral director, and disarming author (Smoke Gets in Your Eyes—and Other Lessons From the Crematory), Doughty here answers a lot of questions she’s been asked by kids, who don’t yet suffer the squeamishness so often afflicting their elders when it comes to death and dying. So, let’s get to it: No, your cat probably won’t eat your eyeballs. Your lips, maybe, but only once the cat gets really hungry. Dogs, though, will snack more indiscriminately. And so it goes: Do conjoined twins always die at the same time? If someone is trying to sell a house, do they have to tell the buyer someone died there? And maybe the best one: At my grandma’s wake, she was wrapped in plastic under her blouse. Why would they do that? OK, it isn’t Proust, but unlike Proust, you’ll almost surely finish this one.

The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last by Azra Raza. Basic Books, Oct. 15.

As her husband’s oncologist, Azra Raza offers a profound, personal account of navigating cancer treatment options that have not changed much in 50 years—for a cancer patient today is as likely to die in the same amount of time as a cancer patient 50 years ago. Doctors are constantly beating the disease back, killing bad cells after they appear—but they’re still struggling to prevent the malignancies from showing up in the first place. Raza weaves literature, personal narrative, history, and science into a compelling truth: Medicine hasn’t triumphed in the “War on Cancer.” Outcomes are as grim as ever, making this book a tough read. The further you get in Raza’s story, the more you understand how much has to change, and how unlikely that change is—the business of curing cancer has become too big to kill, as well.

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson. Doubleday, Oct. 15.

Bill Bryson, author of A Short History of Nearly Everything, should write textbooks to keep bored kids off Adderall. Bryson’s approach to teaching is anecdotal, accessible, and imaginative. The Body isn’t just a physical, circulatory, and neurological map. It’s a story about ourselves and how scientists came to discover the intricacies inside us, how everything conspires to keep us upright and walking around despite some common invaders—bacteria, viruses—that constantly seek to undermine us. Bryson would be a great companion at the doctor’s office, but if he’s not available, his book is handy. This fun ride through the human body will have you simultaneously laughing and blushing about how surprisingly little you know about your personal meat suit.

Bill Cunningham: On the Street: Five Decades of Iconic Photography. The New York Times/Clarkson Potter, Sept. 3.

A retrospective of Bill Cunningham’s 30 years spent cycling through New York City to document street fashion trends that would later influence haute couture, is timely. In the era of the iPhone and “Humans of New York,” it’s good to remember the man who did street fashion photography first and best. Of course, Cunningham was as recognizable as the people in the photographs he took for The New York Times society pages. He was uptown and downtown on his bicycle. He watched as subcultures became mainstream. His images contain the strangest of creatures and the most glamorous, too. He was at the Met Gala for his column Evening Hours and the drag balls for On the Street. He preferred to snap people expressing themselves through clothing over photographing a stylist’s choice imposed on an individual. Personal liberty was priceless to him. Until 1994, when he was hit by a truck, he remained a freelance photographer, only yielding to full-time employment once he realized health insurance was a good idea.

Free S**t by Charles Burns. Fantagraphics, Sept. 24.

Charles Burns, author of the graphic novel Black Hole and early contributor to RAW, has been giving the stuff collected in Free S**t to his close friends over the last couple of decades. So now you can be at the exclusive party with this compilation of almost 20 years of work previously seen by a select few. Through unfinished sketches, polished drawings, centerfolds, characters recognizable to CB fans, and other stuff, readers and art lovers get an all around sense of the kind of guy Burns is—and it’s good.

Rusty Brown by Chris Ware. Pantheon, Sept. 24.

There can’t be many, if any, books—and no graphic fiction—more lovingly, painstakingly, or minutely conceived and executed than Rusty Brown. You don’t have to read a word of the text of this collection of interlocking stories about a boy growing up in Nebraska, or follow even one of the several plotlines it contains, in order to love it. All you have to do it is look at it, from the heavily decorated hardcovers to the detailed book jacket to the pages upon pages filled with the intricate cartoon panels that are the beating heart and soul of this wonderful book. Ware’s narrative sweet spot is the inner lives of uncool, unsure kids. The way he tells it, those lives are not only redeemable but redeeming. Rusty is far more interesting—and admirable—than the superheroes he worships. That nerd in the third row of homeroom finally gets his due. And the best is saved for last: When you are done reading all the stories, when the last page with the final panels is turned, you come upon a two-page, full-color layout with just one word: INTERMISSION

Avedon Advertising by Richard Avedon. Abrams, Oct. 8.

Richard Avedon was one of the most versatile fashion and portrait photographers of the 20th century. He began with Harper’s Bazaar and then went to Vogue, where he shot most of the covers under Diana Vreeland until 1988. Chanel No. 5 was a career mainstay—Coco Chanel herself was his model, and then Catherine Deneuve for just about forever. He encouraged models to move. No human mannequins for Avedon! There were cat fights in Versace ads. In 1974, he captured Brook Shields’ innocence for Colgate, then returned to her for a steamier campaign with Calvin Klein in 1980. He turned models into brands and shot them repeatedly for various products. Once glamour gave way to minimalism and heroin chic, he posed Kate Moss sans makeup and clothes in a stark ad for Calvin Klein underwear—as stark as the unforgiving portraits in the other collections of his work that had nothing to do with fashion.

Making Comics by Lynda Barry. Drawn & Quarterly, Nov. 5.

Finally we have the follow up curriculum to Professor Skeletor’s (aka Lynda Barry’s) bestselling Syllabus that encourages us to communicate in images regardless of artistic ability. Making Comics offers helpful tips for circumnavigating the stick figure by conjuring Ivan Brunetti. Just about anything counts as a drawing as long as it has a few basic elements: Draw a circle head and a triangle body and put arms, legs, and a face on it. Then stick something in its hands or add detail to the clothing. Pretty soon, it’s alive. Doesn’t matter what the drawing looks like. A picture can tell a story and the story can shift. There are no rules to Making Comics other than to turn off the phone and get busy. Lynda Barry is the encouraging voice offering ways to get that hand moving and the ideas rolling.

Quichotte by Salman Rushdie. Random House, Sept. 3.

Meta, meta, meta. A satirical novel inspired by Don Quixote, the most famous satirical novel of all time. The “knight” in this case is a sad-sack salesman hopelessly in love with a TV star. His Sancho is his imaginary son. His quest takes him across America. Nobody ever said the author of The Satanic Verses didn’t have chutzpah.

The Testaments by Margaret Atwood. Doubleday/Talese, Sept. 10.

As if Handmaid’s Tale fever could not get more intense, Atwood fuels the enthusiasm stoked by the TV series and her 1985 novel that inspired it with a sequel, set 15 years after the first book ended.

Akin by Emma Donoghue. Little, Brown, Sept. 10.

On the verge of embarking for the south of France, where he hopes to clear up some mysteries about his mother, a retired professor in New York City gets a call from social services asking if he can help care for an 11-year-old nephew he’s never met. Feeling obliged to help, the professor takes the boy with him on the trip. It’s an education for both travelers and a breeze for Donoghue, who’s forgotten more about the dynamics of adult-child relationships (Room) than most of us will ever learn.

The Water-Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates. One World, Sept. 24.

The tortured history of American slavery and the separation of families provide the structural underpinnings of this tale of Hiram Walker, born a slave, destined to escape the hell of the South but all the while obsessed with reuniting his family. Acclaimed essayist Coates’ fiction debut may be set in the 19th century, but his themes could be taken from today’s headlines.

The Dutch House by Ann Patchett. Harper, Sept. 24.

In her first novel since 2016’s Commonwealth, the author of Bel Canto returns with a story of a century-old mansion and three generations of the broken family that inhabits it.

Grand Union by Zadie Smith. Penguin Press, Oct. 8.

The first collection of short stories from the acclaimed essayist and novelist (White Teeth).

Olive, Again by Elizabeth Strout. Random House, Oct. 15.

Strout’s 2008 novel Olive Kitteridge won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction and sold more than a million copies. Strout looks back in on the tart-tongued, ornery math teacher, now retired, in old age.

The Siberian Dilemma by Martin Cruz Smith. Simon & Schuster, Nov. 27.

Smith (Gorky Park) may be a fiction writer, but his crime novels featuring the durable, laconic policeman Arkady Renko have over the last few decades supplied some of our most insightful coverage of Russia. Smith, for example, was one of the first Russia-watchers to flag that country’s far-right revisionist embrace of Stalin not as a monster but a national hero. In this latest Renko installment, the detective heads to Siberia to find a missing journalist.

Agent Running in the Field by John le Carré. Viking, Oct. 22.

Le Carré is a superb novelist who happens to write espionage thrillers. In his latest effort, the 87-year-old (!) author conjures a world of spycraft that has less to do with Berettas and martinis and everything to do with bureaucracy and personal entanglements that cloud judgment even as they greatly affect the actual workings of the spy trade. Like George Smiley, le Carré’s greatest creation, the 47-year-old Nat in this novel is a tired and somewhat over-the-hill British intelligence operative. But, like Smiley, Nat has more than a few tricks left up his sleeve when the Russia threat again looms.