Writing is a solitary business. The scaffolding behind a work can appear baffling to the non-writer, as can the idea that, even when not putting a single word on paper, the writer might be at work. It is no surprise, then, that the bonds between writers can provide some of our most complex and intimate records of friendship.

The Company They Kept: Writers on Unforgettable Friendships, Volume II, is the second offering on the subject from New York Review of Books. Across the two volumes, the essays chosen by editor Robert B. Silvers cover friendship in a great range of guises, from the fond and funny account of a May-December love affair between Prudence Crowther and the humorist S.J. Perelman to Anna Akhmatova’s touching remembrance of Osip Mandelstam. We are also privy to the admiration Daryl Pinckney felt for his mentor, Elizabeth Hardwick, who told students, “There are really only two reasons to write: desperation and revenge.” Susan Sontag’s portrait of Paul Goodman centers on her ambivalence toward him; she never really felt Goodman liked her, nor was she especially fond of him as a man, but “Everything he did on paper pleased me.”

Another particular highlight is Gore Vidal’s tribute to Dawn Powell, whom he remembers as “a small, round figure, rather like a Civil War cannon ball.” Vidal had turned to drama at that time and Powell confronted him, amusingly: “How could you do this? ... How could you give up The Novel? ... The security of knowing that every two years there will be–like clockwork–that five hundred dollar advance?” Great names run throughout these volumes: Oppenheimer on Einstein; Murray Kempton on Sinatra; Bellow on Cheever, and dozens more, a rich and varied set of reminiscences.

Few of us are fortunate enough to be the subject of the sort of loving, incisive portraits as those which appear in these two volumes. “A memoir of a talented friend risks sentimentality,” Silvers writes in the preface to the first volume. But to the credit of the writers whose work is featured, and Silvers’s credit as editor, these pieces seldom hit a false note. Here are 10 other literary friendships which are also unforgettable:

The great poets met in the last decade of the 18th century and remained friends for 15 years thereafter, during which time they collaborated on the first volume of Lyrical Ballads, which marked a seismic shift in the tastes of the English reading public. In time, though, their friendship soured – Wordsworth included a poem of his own in place of Coleridge’s “Christabel” in the second volume of their collaboration, and some years later, he learned that Coleridge thought of him as “a rotten drunkard.” Nonetheless they are inextricably linked, long after their initial, fruitful bond dissolved. Adam Sisman traces their ups and downs in The Friendship: Wordsworth and Coleridge.

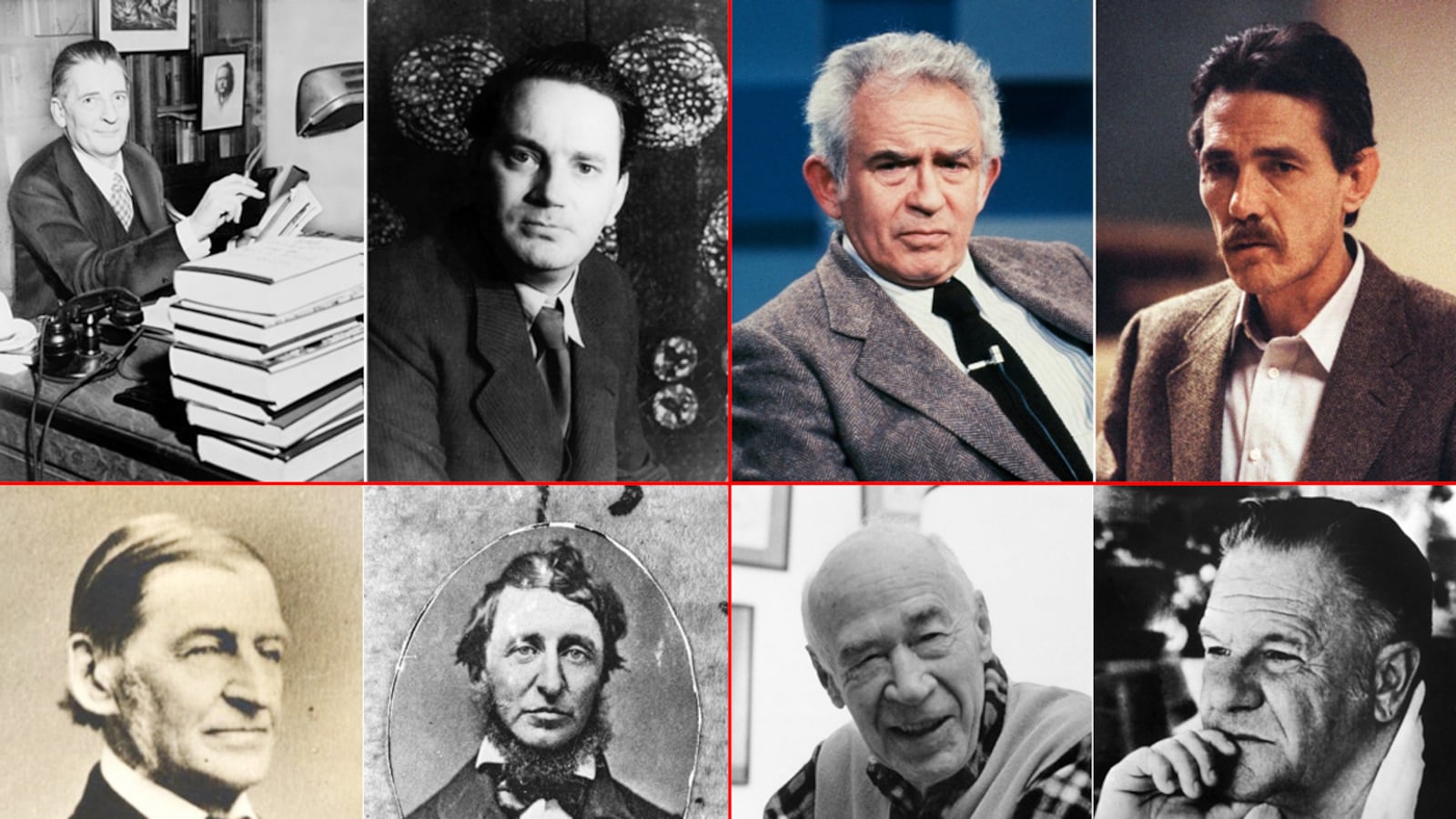

AP Photo (2)

Few names in literature are more frequently paired than Boswell and Johnson. From 1763 onward the men were friends. Boswell’s admiration of Johnson, who was highly esteemed for his Dictionary of the English Language, led him to undertake the writing of a book about his friend, surely a project neither man imagined having such a massive impact. Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson was published in two volumes in 1791, following more than a decade of work. It marked a great leap forward from biography as written up to that point, and is widely considered one of the finest books of its type. Both the friendship and the making of Boswell’s classic book are examined in Boswell’s Presumptuous Task by Adam Sisman.

World History Archive / Newscom

Emerson and Thoreau were kindred spirits, major figures in the Transcendentalist circles of the 19th century. Emerson was 14 years Thoreau’s senior and acted as a mentor to the younger man, first in a highly supportive manner but later with a more critical eye. By 1850, they had drifted apart somewhat—they had known one another for more than a decade by that time—and while Thoreau appears to have taken the rift harder than his mentor did, no one has managed to provide a definitive answer to what was behind the shift in feeling. Emerson and Thoreau: Figures of Friendship chronicles their bond in considerable detail, in a series of essays by scholars from various disciplines.

Arthur Rimbaud was an aspiring poet when he tracked down Paul Verlaine in 1871. Their relationship in the following years was dynamic and unpredictable, fueled by drugs and drink. Verlaine favored absinthe and Rimbaud began to partake as well. Verlaine left his young pregnant wife to live in the carefree style Rimbaud favored. The two poets were lovers (though not to hear Verlaine tell it, at least in print). Their affair ended in appropriately dramatic fashion. Young Rimbaud attempted to sever ties with Verlaine who, perhaps frazzled and worn by the intensity of their exploits, shot the younger man in the wrist. Their tempestuous relationship has been recorded in a number of places. In the past few years Edmund White’s Rimbaud: The Double Life of a Rebel, and Bruce Duffy’s novelization of Rimbaud’s life, Disaster Was My God.

Newscom

Thomas Wolfe was a prolific writer. His novels ran well beyond commercially viable length, and it fell to the legendary editor Maxwell Perkins at Scribner to trim them. The process was at times contentious; Wolfe was fiercely protective of his work, and resistant to the cuts Perkins deemed necessary. In the case of Look Homeward, Angel, for instance, Perkins excised more than 100 pages from the original manuscript. They had fallings out, as would be expected in such a relationship, but through it all, Wolfe viewed Perkins as a close friend. What could be better evidence of this than the fact that Wolfe, so vigilant in defense of his work, named Perkins his literary executor?

Lawrence Durrell wrote to Henry Miller after reading Tropic of Cancer. Durrell, of course, is not the only writer Miller enthralled; James Salter has said that Miller’s voice “makes you want to linger at his elbow until long past closing time.” And, in time, Miller invited Durrell to linger. He became part of Miller’s Villa Seurat circle, and the two men grew to be friends. They spent time together on Corfu, and corresponded when apart, from the 1930s all the way to Miller’s death. Those letters were published as Lawrence Durrell and Henry Miller: A Private Correspondence.

AP Photo; Getty Images

Ginsberg and Kerouac became friends in the 1940s. Ginsberg was 17 and Kerouac was 21 at the time. They remained friends until Kerouac’s death in 1969. They were fathers of the Beat Generation, Ginsberg perhaps the movement’s best known poet, and Kerouac the most prominent novelist. Their openness and daring marked them as major talents, particularly at a time when America had not yet experienced the upheaval of the 1960s. Their frenetic, eventful lives and their friendship play out beautifully in the course of their correspondence, which was published in 2010 as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters.

AP Photo (2)

For many years, Nabokov and Wilson enjoyed great mutual respect. Wilson was helpful to Nabokov upon his arrival in America, though it is difficult now to imagine the formidable Nabokov needing much assistance from anyone. Wilson was drawn to Russian literature and subsequently the Russian language, subjects on which Nabokov could fairly be called an expert. Their most contentious moments came when Wilson was critical, in print, of Nabokov’s four-volume translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin. They crossed swords in The New York Review of Books, with Nabokov casually asserting his superior facility with the Russian language. Their letters were published as Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya: Correspondence between Vladimir Nabokov and Edmund Wilson, 1940-1971 and, curiously, show little evidence of ill-feeling related to the public dispute.

Jack Abbott was serving time in the Utah State Penitentiary when he learned of Norman Mailer’s work on The Executioner’s Song, an account of the life of convicted murderer Gary Gilmore. Abbott’s letters (there were roughly 1,000 of them) impressed Mailer favorably. Mailer had considerable fame at the time, and arranged for a selection of the correspondence to appear in The New York Review of Books. He was not alone: Random House published selections from the letters as a book entitled In the Belly of the Beast. Mailer campaigned for Abbott’s release, and it was granted in April of 1981. Abbott, Mailer believed, was a significant new literary talent, and perhaps he would have been, if not for the fact that he murdered a man named Richard Adan some six weeks after being released. Abbott returned to prison. Mailer was contrite, and the friendship, such as it was, came to an end.

John Bayley met Iris Murdoch in the 1950s at Oxford. He had no idea at the time that she was a novelist (her first book was finished but not yet in print), nor was he entirely sure of her interest in him. She seemed to have discrete spheres of friends, and Bayley was unsure how he stacked up next to some of them, though her fondness for him gradually became apparent. They were married for more than 40 years, during which time Murdoch built a reputation as one of the finest English novelists of the day, winning the Booker Prize in 1978 for The Sea, The Sea. Sadly, Alzheimer’s disease struck Murdoch toward the end of her life, a turn of events Bayley chronicles in his lovely memoir of their life together, Elegy for Iris.