This week, Dior scrapped the advertising campaign for its fragrance Sauvage after it was accused of cultural appropriation and insensitivity.

Dior had consulted with Americans for Indian Opportunity in creating the campaign, but received criticism over its use of stereotypes, the word “Sauvage” (seen as too similar to the word “savage”), and the presence of Johnny Depp in a landscape-based commercial, which majored on his experience as a white man rather than Native Americans who provide Depp’s brooding self with a decorative backdrop.

Over the past several years, many fashion brands have found themselves in trouble for cultural insensitivity and alleged racism. What’s astounding is that in the year 2019 corporate ignorance still flourishes.

Surviving public fallout isn’t as easy as it used to be either. Business of Fashion reported that Dolce & Gabbana sales fell in China after backlash from a racist ad and comments made by Stefano Gabbana. U.S. shoppers seemed to have cooled on Gucci following the black face sweater controversy, with their sales lagging in Q2.

Last December, as reported by The Daily Beast, Prada shut down a New York City storefront and pulled a $550 keychain from its stock after the accessory went viral for resembling blackface imagery.

Coach, Givenchy, and Versace recently found themselves in controversy in China where they all had to apologize for producing T-shirts that were regarded as having undermined the country’s “One China Policy”, which states there is only one sovereign state under the name China.

The apparel in question identified the semiautonomous regions of Macao and Hong Kong as countries, causing an online firestorm, and resulting in actress Yang Mi dropping her brand ambassadorship with Versace. Unfortunately for the brands, there is no instant fix for these controversies.

“There is no format to figuring out how to deal with these problems yet,” said Iris Chan, international client development director and partner at Digital Luxury Group. “These kinds of controversies, specifically in China, once they happen, they spread. If one brand does something, then a witch hunt begins to find another brand to take down for the same offense.

“There’s a number of factors at play for why these things happen. For brands that are not in these foreign markets as much or don’t have people on the ground there to be a guiding board for cultural sensitivity, they see these types of controversies happen.”

Chan acknowledges that while many of these problems are not unique to China, Chinese consumers are more vocal now thanks to social media, and with a country of 1.3 billion people, they are easily heard. Asian and Asian-American consumers won’t tolerate spending money with brands they feel disrespected by.

Chan’s colleague, Pablo Mauron, a fellow partner and managing director for Digital Luxury Group in China, said that, “Social media is a way to check the pulse of the general opinion. What’s funny is that any brand should be able to avoid these controversies by asking the opinion of local people, but opinions aren’t asked for until after the fact, and it’s amplified with a million voices behind it.”

Even with the University of Google at our fingertips, neither Mauron nor Chan sees a simple solution to these problems becoming apparent anytime soon. “Having more voices in the conversation that aren’t all one-sided, from one perspective, from one culture, and one view will help,” Chan said. “However, that won’t solve everything. There’s still some levels of common sense that need to be put in place.”

Mauron added, “Some brands do have great local teams in place, but there are still consumers who end up feeling disrespected, and the cause and origins of that are often obvious.”

Many of these companies would do well to add a human checkpoint to their production process. Marie Tulloch is a senior client services manager at Emerging Communications U.K., a company focused on B2B, education, and beauty brands ensuring clients have the best possible experience reaching out to Chinese consumers abroad and in the U.K..

Tulloch, who has handled her share of crises over her years working in communication, said, “Part of the issue with these cultural controversies is the lack of human touch or human reasoning. Brands need to look at these things through a cultural lens.

“The Western view has always been the prominent view, and designers and marketing people aren’t used to having to culture check their content. They are used to putting it out there and it being accepted whether that consumer was Western, or from APAC countries, or from China. Everything Western was once seen as new and cool.”

She added, “In other countries, especially China, there is so much national sentiment and pride, anything that threatens or demeans that becomes a big issue for consumers. The current internet generation is more vocal than their predecessors and are more willing to voice opinions if they don’t like something. Things are rolled out from a global standpoint, and the companies find out about issues later down the line.”

Aliza Licht, a fashion industry public relations veteran and author of Leave Your Mark: Land Your Dream Job. Kill It in Your Career. Rock Social Media, says that a large part of the issues still surfacing today are due to lack of diversity within companies.

“Lack of diversity is the core of the problem,” she said. “When designers surround themselves with only one type of person, those are the only people they end up hearing from. Human resource departments need to think about the type of talent being hired and how to add diversity and different backgrounds. When you don’t have people along the journey to say things like, ‘That offends me, or it might offend other people,’ then a crisis can happen.

“There needs to be those sorts of stopping points along the design process where employees feel comfortable speaking up to say these things are problems. The problem is, if you are the minority in the room, which can already be uncomfortable, you need to be in an environment that empowers you to say, ‘That’s not a good idea.’ It’s important not to squash those voices.”

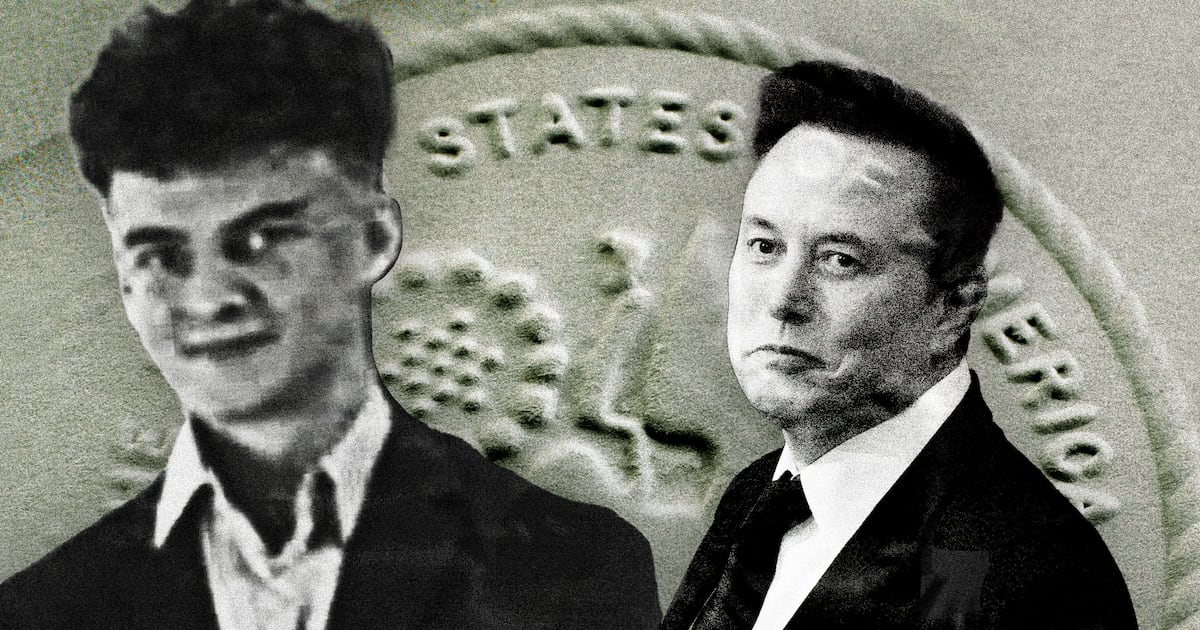

Licht believes that in addition to diversifying their employee pool, companies can avoid these controversies through media handlers. “Not every CEO in the world needs a Twitter handle,” Licht said. “If you have a CEO or executive that can go tweeting things that can make the company look bad, that’s someone that doesn’t need to be on Twitter.

“I spent most of my career working with other publicists who very carefully contained their clients’ mouths and social media feeds. It’s entertaining to read all these scandalous tweets and see everyone’s true colors, but if you’re a company with someone that can fly off the handle at any minute, you need to know that’s not someone who should have a Twitter handle.”