Don Thompson, the chief executive officer of McDonalds, makes more in a day than the average fast food employee makes in a year. And some employees are starting to get upset.

In the latest in a string of recent actions designed to call attention to low wages and abusive labor practices, employees of some of America’s largest fast food chains—McDonalds, Burger King, KFC and Taco Bell—on Monday joined protests in Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit, Milwaukee, Kansas City, and Flint.

Once viewed as the go-to part-time job for teenagers (PDF), jobs in the fast-food industry are increasingly occupied by older workers seeking to support families. The median worker age is over 28 according to BLS data cited by The Atlantic. But as the fast food industry continues to grow, wages have not kept pace. The real value of the minimum wage has decreased continuously since its peak real value in 1968 (PDF), while living costs have risen. A full-time minimum wage employee makes $15,080, well below the poverty line for a family of three.

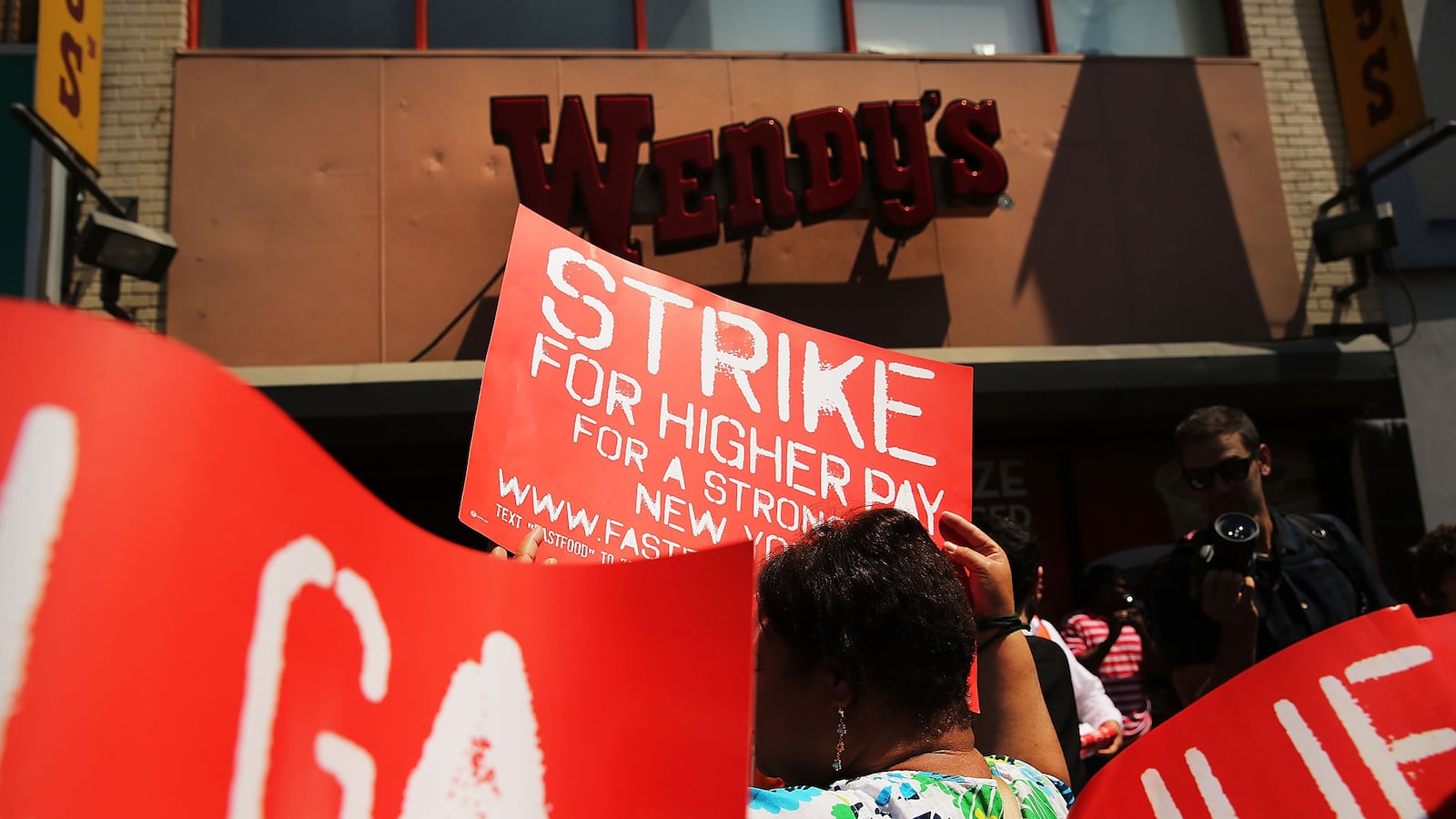

Last November, similar protests took place at fast food chains across New York City. The demands this time are similar, as workers have yet to gain anything close to the $15-an-hour they called for last fall.

Shanelle Young, a Wendy’s employee at the protest in New York’s Financial District, described frustration at trying to support a child on minimum wage working 35 hours a week. “Half of these people ask for more hours,” she said. “It’s unfair. People have kids to raise.” But with healthcare reform legislation mandating that employers provide health benefits to employees working over 30 hours a week, fast food companies have a greater incentive to keep as many of their workers as possible in part-time positions. (Acknowledging as much led to a huge backlash for Papa John’s CEO John Schnatter.)

The Wendy’s that served as the venue for the protest in the Financial District on Monday was not closed, and neither was the Union Square McDonalds that served as the backdrop for another rally later in the day. Young said that many employees were afraid to participate because managers said there would be consequences.

The protesters, many of whom heard about the protest from organizers from the Service Employees International Union, were joined by representatives from Fast Food Forward, whose petition for higher industry wages in New York has garneredmore than 124,000 signatures. Workers have mobilized with Fast Food Forward under the slogan, “Can’t survive on 7.25!” Kay Smithe, another Wendy’s employee at the Financial District protest, lives with her mother because she cannot support herself on her minimum wage salary. She described coworkers having hours cut back, and said those who are given full-time employment working six-hour shifts without breaks. She criticized high executive compensation in the industry and said she believes protests will succeed because “in the end, solidarity wins out.”

Efforts to unionize are rare but not unheard of in the fast food industry. In 2010, employees of the Minneapolis branches of the sandwich chain Jimmy John’s attempted to unionize to fight low wages and unfair treatment of ill workers. The union activists were ultimately unsuccessful, and the chain fired six of the workers responsible for organizing, though they were later reinstated with back pay by an administrative law judge for the National Labor Relations Board. Starbucks and Whole Foods have also been involved in long term struggles over union formation with employees.

Union-friendly legislation has not fared well in recent years. The Employee Free Choice Act, a bill amending the National Labor Relations Act by allowing workers to form unions if officials can get signatures from a majority of workers, passed the House in 2007 but died in the Senate. It failed again in 2009. Legislation to increase wages has also stagnated. The Catching Up to 1968 Act of 2013, sponsored by Congressman Alan Grayson of Florida and endorsed by a laundry list of economists proposes raising the minimum wage to $10.50 with automatic increases indexed to inflation. It was introduced in the House in March and was referred to the Subcommittee on Workforce Protection a month later, but has made no progress since.

Since they provide a product that derives its appeal largely from its low price point, fast food companies have a strong incentive to keep costs down. One analysis of 160 studies in the American Journal of Public Health found that among all food categories, consumers are most sensitive to price changes in food away from home, reducing consumption by 8 percent for every 10 percent increase in price.

But workers argue that in the case of fast food, a $160 billion a year industry with executive compensation in the millions for many industry leaders, there is room to pay workers a living wage. In 2013 McDonald’s CEO Don Thompson received a compensation package valued at $13.8 million, made up of a base salary, stock awards, options, and incentive pay. The average fast-food worker in New York City makes $11,000 annually, according to Fast Food Forward.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (PDF), only 8% of American workers belong to unions, a decrease of around 20% over the last decade—in the private sector, the figure is 6.6%. Employees in food preparation and service have one of the lowest rates of union membership across all occupations, coming in at only 3.7% in 2012.The only occupations with lower union participation rates were Sales and Farming, Fishing and Forestry, with 2.9 and 3.4% participation, respectively.

Penny Lewis, an assistant professor of labor studies at CUNY, was among the crowd of over 100 that gathered at a McDonald’s in Union Square for one of the protests. “It’s inspiring and necessary given the current labor market and the direction the economy has taken towards low wage work,” she said. “They’re up against long odds.” Lewis expressed skepticism that pro-labor legislation would pass without pressure from the kinds of protests currently taking place.

One of the greatest challenges faced by workers seeking to organize is one of scale. McDonald’s and Burger King alone have over 20,000 locations in the United States, and garnering a critical mass of support among employees seems like a nearly impossible task. Nevertheless, protesters expressed optimism. “This one’s going to be different,” said Elvis Guerrera, a Burger King employee who heard about the protest from SEIU activists who came to his job. “As things get more expensive, people are getting more and more frustrated and they’re not going to take it anymore.”

Meanwhile, at the Burger King around the corner from the Wendy’s protest, a banner advertising the $1.29 Whopper Jr. hung in the window and five cashiers manned the registers as lunchtime traffic began to pick up. Despite the chanting of the protesters echoing from around the corner, it was business as usual.