I first met Rick Bass in the late 1980s at George Plimpton’s townhouse, at a party jammed with literary folks eager to meet the young author of The Watch. Bass’s first story collection had launched an important fiction writer, already anthologized in New Stories from the South 1988 and the 1989 O.Henry prize anthology and honored with a PEN/Nelson Algren award. Bass ended up being one of the authors Plimpton touted when talking up The Paris Review (“It’s where the early work of Philip Roth appeared, and Rick Moody, Rick Bass, T. Coraghessan Boyle, Richard Ford, Terry Southern…” was a standard Plimpton line).

“He was such a champ for me,” Bass recalled the other day. “He published so many stories and essays, even poetry—maybe a dozen pieces over about the same number of years. I miss him and the incredible fun he brought to everything.”

Bass looked slightly out of place at that long-ago Paris Review party, despite being the centerpiece of the evening. He said he was living in a valley in Montana, which seemed a non sequitur in that setting. But sure enough, Bass, who was born in Texas and worked as a petroleum engineer before turning to writing, had moved to Yaak Valley in northwestern Montana in 1987.

Montana’s outdoors culture suited him—he grew up hunting and fishing with his dad—and gave him solitude to write. The two activities work well together, he told me. “The cells are electric with focus and awareness, when hunting—this is pretty good cross-training for inhabiting the emotion of a story, in the writing process. Searching for something you can’t see, but which you believe or hope is out there, is also pretty much like what the story-writing process is for me.”

He has continued to live with his family in relative isolation. (He has called the Yaak “my garden—the tiny million-acre island of the Yaak, which exists like one powerful shining cell in the bloodstream arterial of the once-upon-a-time wildness that stretched, and might still stretch again, from the Arctic tundra down to the farthest reaches of Yellowstone and beyond, hundreds of millions of acres of sanity, logic, and the radiant and uninterrupted grace of wild things.”) He’s published more than two dozen books. His story collection The Hermit’s Story was a 2000 Los Angeles Times Best Book of the Year; his memoir Why I Came West was a finalist for the 2008 National Book Critics Circle award.

He also has been deeply involved in environmental issues, drawing comparison to Wallace Stegner for his eloquent writing inspired by love of the land. He was arrested at the White House in February while protesting the Keystone pipeline.

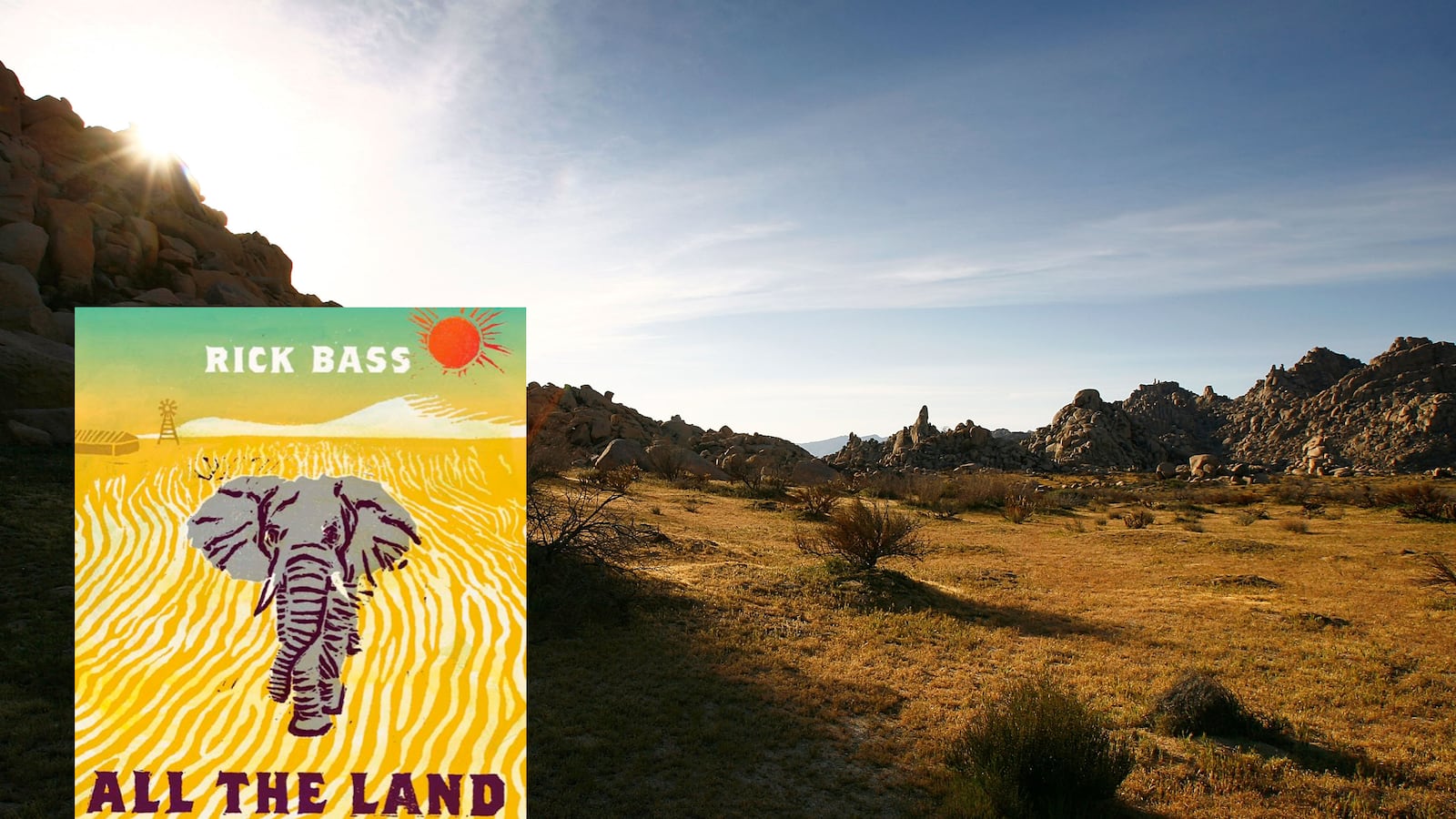

Bass’s majestic new novel draws upon his passion for the land, and also on his background as a geologist in the oilfields in north Alabama and Mississippi. All the World to Hold Us is set in a vivid imaginary landscape: a desert land he calls Castle Gap in West Texas, Horsehead Crossing, and an inland salt lake, Juan Cordoba Lake.

“I have never seen this place, these places—but have seen similar landscapes throughout the West, on a smaller scale,” Bass explained. “I magnified and imagined a landscape to fit the novel, or a hybrid-landscape. I’m not sure what drew me to write about it. The novel is about desire, and it strikes me that landscapes that are typically characterized by paucity, such as deserts, are a perfect vessel or reservoir for holding vast quantities of desire.”

Bass says he “kind of identifies with” Richard, the geologist who anchors the novel. Richard has a “vision for various things—not just for hidden oil and fossils, but the power of landscapes, the magic spirits beneath seemingly inanimate masks, and the places of refuge and sanctuary.” This geologist narrator works with a drafting pencil, “reconstructing the topography of an old, old world below, partly by data and partly by intuition. Seeking the oil, and seeking the gas, with the sharpness of hunger known to any hunter.” Finding oil is indeed an intuitive process, Bass said. “I grew up in a milieu in which searching, moving forward looking for things that were not visible or apparent was the baseline. I can’t help but think that has influenced me as a writer.”

Bass has populated the novel with characters driven by obsession. Richard is driven by his need to hunt beneath the surface—and his love for his girlfriend Clarissa. Clarissa is obsessed with keeping her fair skin protected from the sun, and getting out of Odessa, Texas. Omo, a German immigrant, is obsessed with harvesting salt from the lake. Herbert Mix is obsessed with harvesting skulls, bones, fossils, pocket watches, and other treasures, from beneath the earth’s surface.

And the oil men in the novel are obsessed with finding oil and gas and striking it rich. What else drives them? “I think at that level the acquisitive hunter-gatherer gene influences them more than riches,” Bass said. He hasn’t been in West Texas and the region of Mexico at the base of the Sierra Madres where the novel is set in nearly thirty years. “For me, now, it’s all memory and imagination.

He has filled the novel with mythic stories—of a circus elephant lost in the desert, of a skeletal wagon train found intact, with horses still in harness. “A strange and powerful landscape summons strange and powerful happenings,” he writes. These stories seem to be based on truth or legend, but are, he said, invented.

Bass’s early stories were as clipped as Hemingway’s (“Mexico,” the first story in The Watch begins, “Kirby’s faithful. He’s loyal; Kirby has fidelity. He has one wife, Tricia.”). All the Land to Hold Us, is layered with paragraph-long sentences that meander from one rich clause to the next, ending with surprising yet predestined conclusions. They beg to be read aloud. This was an intentional stylistic choice for the new novel, Bass said. “I love hearing stories read aloud and find that as I get older and write slower, I often speak the words as I am writing them. And definitely the phrasings and transitions and conjunctions are in line with the idea of strata and repetition-with-curious-variances.”

The tone he intends is “hopeful, hope tested, waiting, sustained anticipation and hope. Sustained yearning and exploration of those yearnings.”

To what extent is his description of the environmental damage caused by oil drilling up to date? “I go pretty light on the real-time aspects of drilling and production (and transport); about the worst thing a writer can do in fiction is to preach, and anyway, How unoriginal would that be, for oilmen to be naughty? Equally stiff and forced however would be to try to make them be swells, for contrast’s sake. So instead I tried to make them be interesting, but neither good nor evil—just hungry, hungry, hungry, like almost everyone in this novel.”

I asked if he ever thought back to the time when his life as a writer began.

“I do think back surprisingly often to the earliest days,” he said. “I guess as people like Plimpton and Carol Houck Smith and Harry Foster depart—people who helped me—I remember those early days. Hanging out with Ron Carlson, Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, among the living, thank goodness, and, departed, Eudora Welty, Barry Hannah, and my dear friend, Larry Brown. It was all so new and I was so hungry: such a sponge. I’m actually working on a big book project, Eating with My Heroes, where I travel around the country (as well as to France, to see John Berger), where I visit my literary mentors and cook a nice meal for them and tell them thank you, and also introduce one of my mentees—one a fiction writer, the other a nonfiction writer—to them.”