If you believe prosecutors, Richard Wershe Jr. is serving a life sentence for cocaine possession.

If you believe Wershe, he’s really behind bars because he put away crooked cops and the mayor of Detroit’s nephew.

Either way, Wershe has been paroled after 30 years.

On Friday, Michigan’s longest-serving prison inmate jailed as a juvenile for a non-violent drug offense was granted parole from a life sentence by a unanimous vote by the parole board. It was four days short of his 48th birthday.

“I’m coming home,” an emotional Wershe told his lawyer’s secretary in a call from Oaks Correctional Facility in Manistee, Michigan.

In an email, Wershe said he hasn’t been able to sleep all week.

The news of his pending freedom was delivered by the prison warden’s assistant.

"He was obviously emotional," Eric Smith told The Daily Beast. "I sat with him for about two hours and we talked about the future and the next steps. Pretty much what you would expect from a guy waiting for news that changes his life."

His life is being turned into a movie including Matthew McConaughey set to be released next year. Wershe told a TV reporter: “White Boy Rick is dead.”

This is how “White Boy Rick” was born.

Wershe’s involvement in the drug underworld began when the FBI recruited him as a confidential informant at age 14. He had not been involved with drugs before then. Wershe was a streetwise white kid in an increasingly black Detroit neighborhood. The youngster was known and trusted by the leaders of the Curry Brothers, an up-and-coming black drug gang that was the target of an FBI investigation.

FBI agents listed Richard J. Wershe Sr. as their official informant in the agency’s files, but the intelligence actually came from the younger Wershe. The boy’s father, a self-described business hustler, was happy to receive FBI informant money for things his son knew about dangerous criminals. (Wershe Sr. died in 2014.) Records were falsified to cover up that a juvenile was the FBI’s source. Several retired FBI agents have come forward and admitted the younger Wershe was the real informant.

Young Wershe was good at being an informant. In fact, Wershe was too good, as detailed in a previous Daily Beast story.

Not only did he brief the FBI about drug trafficking, he also told the agents about obstruction of justice by the head of the Detroit Police homicide section to protect gang leader Johnny Curry. After he was convicted and sent to prison, Curry told FBI agents he paid a $10,000 bribe to Detroit Police Homicide Inspector Gilbert “Gil” Hill to divert a murder investigation away from the Curry gang.

Members of the gang had inadvertently killed a 13-year old boy. FBI files show police feared an honest homicide investigation because Curry was married to Cathy Volsan Curry, the niece of then-mayor Coleman Young, who ruled Detroit like an emperor for 20 years. Young was known to end the careers of police command personnel who crossed him.

Inspector Hill later became chief of police and president of the city council before he died in 2016. Hill was never indicted for the cover-up.

Not only did Wershe implicate Mayor Young’s extended family, he got involved with Young’s niece, Cathy Curry (née Volsan), after Johnny Curry went to prison.

Young sought revenge, according to Wershe’s late attorney.

“Stay out of this,” William E. Bufalino II quoted Young telling him. “This is bigger than you think it is.”

Wershe’s intel about the killing of the boy and Inspector Hill’s cover-up meant his role as an FBI teen informant was increasingly at risk of public exposure. The Detroit FBI and U.S. Attorney’s Office dropped him as an informant without warning.

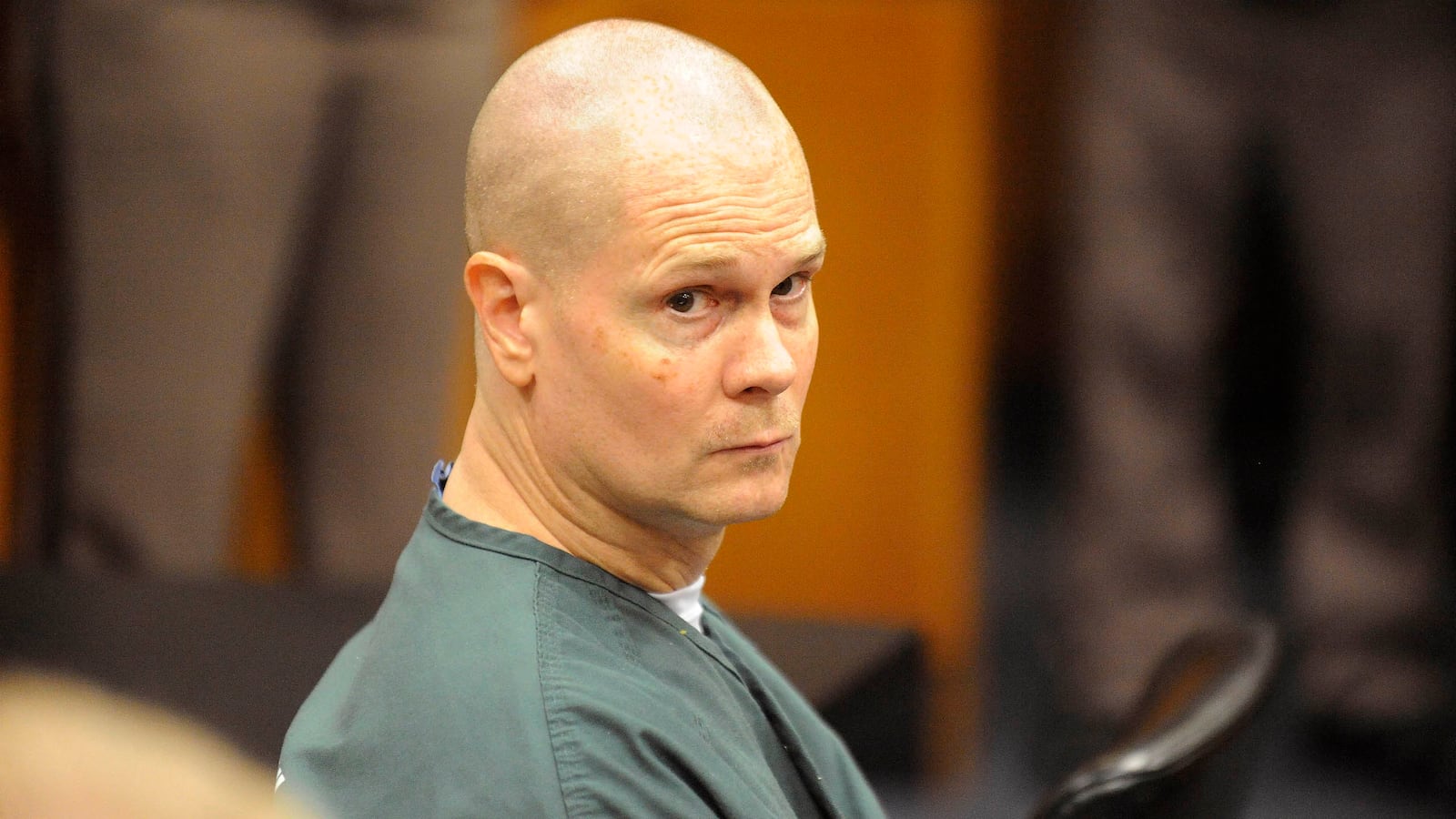

Police photo of Richard Wershe Jr., 1988

Facebook/Free Rick Wershe Jr/Michigan Department of CorrectionsAdrift and out of money, Wershe turned to the only trade he knew — the one the police had taught him: drugs.

Wershe tried to become a cocaine wholesaler, but he didn’t make it. He was busted by the Detroit police with more than 17 pounds of cocaine when he was 18.

Wershe’s case became a media feast. Local papers and TV stations churned out sensational but dubious stories depicting a white teenager as the godfather of the deadly multi-million-dollar cocaine trade in Detroit’s inner city. There was no evidence to support stories that a baby-faced white kid was a drug lord or kingpin ruling the roost and calling the shots amid adult black criminals in a multi-million-dollar criminal enterprise, but the White Boy Rick tale became a local legend, anyway.

Wershe was convicted and given a mandatory life sentence by a Michigan law that has since been discarded. The FBI and federal prosecutors did not step forward to help his defense because they would have had to admit they had been using a teen informant.

Wershe’s only previous parole hearing, in 2003, was a sham built on demonstrably false law enforcement testimony. Wershe was described as in the top echelon of Detroit’s drug underworld, yet police and court records show he was never charged with drug racketeering, conspiracy or operating a continuing criminal enterprise, the usual charges brought against major dope dealers. Wershe was never named as a co-conspirator, un-indicted co-conspirator or even as a trial witness in any of the major drug trials of that era. He was never charged with a violent crime or with ordering a violent crime. He admits he was guilty of selling drugs but he and his supporters say the punishment has been totally out of proportion. Admitted drug hit men who have killed multiple victims have been imprisoned and released in the time Wershe has been behind bars.

“I told on the wrong people,” Wershe said.

Rick, his lawyer (William E. Bufalino II), and parents outside the courthouse during his trial in 1988.

Facebook/Free Rick Wershe JrHis lawyer, Ralph Musilli, agrees. “He cost some powerful people a lot of money,” Musilli said.

Retired FBI agent Gregg Schwarz concurs: "He is in prison for the politics of the City of Detroit."

Another retired FBI agent, John Anthony, says Wershe was arguably the most productive drug informant the agency had in Detroit in the 1980s. In addition to the Curry drug case (the reason for his initial recruitment as an FBI informant), Wershe helped send a dozen corrupt police officers to prison, along with the common-law brother-in-law of Mayor Young.

But Wershe won’t be marching out of the prison door anytime soon. He still faces two years in prison in Florida after he pleaded guilty to participating in a car-theft fraud scheme while he was serving time for the drug case. His attorney plans to petition the Florida judge to modify the sentence to be concurrent with his Michigan case, rather than consecutive. Wershe said he was trying to help his mother and sister earn money when he got caught up in the auto case.

If Florida revises Wershe’s sentence there to run concurrent with his Michigan sentence, he could be out of prison by the middle of August. He’s had multiple job offers, including two phoned in to his attorney’s office after the parole decision was announced.

Wershe didn’t learn a craft or trade in his 29-and-a-half years in prison because the corrections system isn’t geared toward rehabilitation. It’s all about punishment.

Even so, in a hearing before the Michigan Parole Board last month, Wershe said of a legitimate career, “I’m willing to learn.”

Asked why he should be released, Wershe said, “I’ve lost 30 years of my life. All I can give you is my word. I’ll never commit another crime.”