The U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Monday finally gave America’s most popular COVID-19 vaccine—the two-dose messenger-RNA jab from New York pharma Pfizer—full, unqualified authorization.

Experts hope full licensure, along with the expected expansion of vaccine eligibility to include Americans under the age of 12, will nudge hesitant parents to vax their kids. Getting the youngest Americans jabbed is shaping up to be a critical battle in America’s long, painful war with COVID.

Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock hailed the Pfizer authorization as a confidence booster. “While this and other vaccines have met the FDA’s rigorous, scientific standards for emergency use authorization, as the first FDA-approved COVID-19 vaccine, the public can be very confident that this vaccine meets the high standards for safety, effectiveness and manufacturing quality the FDA requires of an approved product,” Woodcock said in a statement.

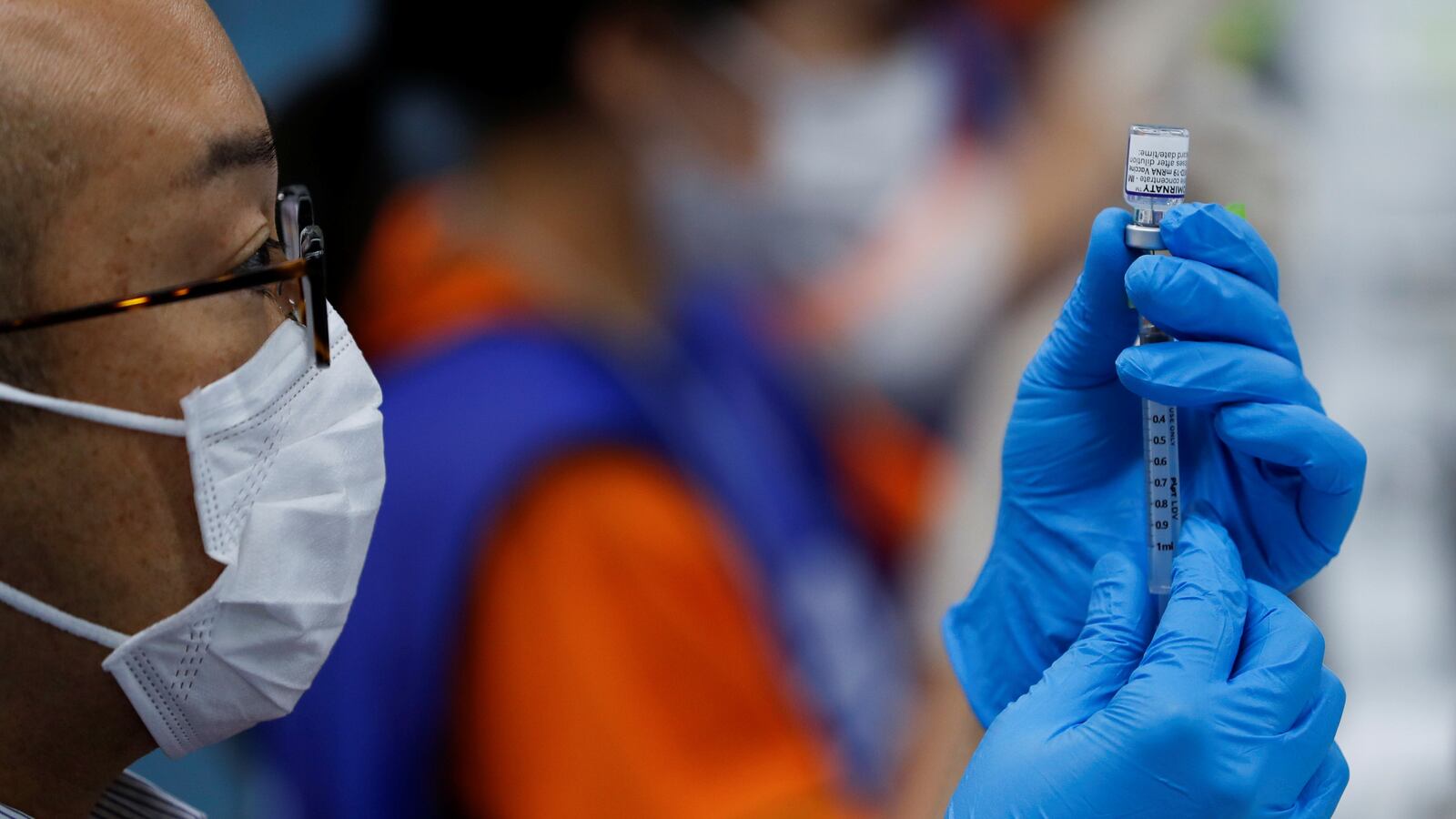

In its announcement, the FDA said the Pfizer vaccine will be rebranded as Comirnaty. It’s been approved for anyone over the age of 16 and will retain emergency use authorization for minors 12 through 15 years of age, and for giving a third booster shot to people who are immunocompromised.

The licensure comes nine months after the FDA granted Pfizer an emergency-use authorization that allowed the company to begin shipping doses. More than 100 million Americans have gotten the Pfizer jab, making it by far the most popular of the three vaccines with some level of FDA approval.

The Pfizer vaccine has proved overwhelmingly safe and highly effective. The FDA’s belated stamp of full approval won’t change how the vaccine is manufactured, distributed, or administered. It won’t change how safe and effective the jab is.

But it might change minds, Woodcock noted. “FDA approval of a vaccine may now instill additional confidence to get vaccinated,” she said.

Skeptical parents of school-age kids are especially important as the U.S. struggles to build population-level “herd immunity” against COVID. Experts aren’t sure what percentage of Americans need vaccines or antibodies from past infection before the country reaches herd immunity—80 percent? 90 percent?—but it’s clear that a high youth vax rate is a prerequisite.

People under the age of 18 make up a quarter of the population, after all. “The math doesn’t work without most children getting the vaccine,” Irwin Redlener, the founding director of Columbia University’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness, told The Daily Beast. “But getting large numbers of parents to agree to vaccinating their kids may well be a major political [and] ideological battle and an unprecedented public-health messaging challenge.”

Unqualified FDA approval of the Pfizer vaccine could help this messaging. For some vax-hesitant parents, a formal stamp of approval from the feds might be just the thing to finally break through the skepticism. “Some people may think, ‘Now I can trust it,” Paul Offit, a director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said of the Pfizer vaccine.

There was a time, not long ago, when the FDA either fully approved a drug or didn’t. There was no such thing as an emergency authorization.

AIDS changed everything. The disease spread so quickly and killed so many people in the 1980s that Anthony Fauci—then and now the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases—helped create a so-called “parallel track” for releasing certain urgently needed drugs that didn’t have the usual, extensive safety and effectiveness data behind them.

A 2004 law, motivated in part by a post-9/11 fear of biological terror attacks, created a formal emergency-use authorization process that was essentially a codification of Fauci’s parallel track. Under EUA, the FDA can release a vaccine or other biological product on an emergency basis after reviewing data from large-scale trials.

While the drug begins circulating, the FDA keeps an eye on its long-term safety and effectiveness, aiming to eventually upgrade emergency authorization to full authorization. If there are signs something might be wrong, the FDA can yank EUA and halt distribution of the drug. That’s exactly what the agency did with hydroxychloroquine, a malaria drug that then-President Donald Trump touted as a COVID treatment early in the pandemic.

Under pressure from Trump and his allies, the FDA gave hydroxychloroquine emergency approval for COVID patients back in March 2020. But evidence of its effectiveness was thin. And there were worrying signs the drug was contributing to cardiac problems in some takers. The FDA revoked the EUA in June 2020.

In contrast to hydroxychloroquine, the Pfizer vaccine has continued to be safe and effective even as the number of doses administered in the U.S. exceeds 200 million. For that reason, the belated full authorization came as no surprise. “In a more rational world, it wouldn’t mean anything,” Offit said.

This is not a rational world, however. Despite the overwhelming evidence that the COVID vaccines are safe and highly effective—and despite a surge in COVID infections resulting from the spread of the highly transmissible Delta variant—as many as a quarter of American adults say they won’t get vaccinated.

The hesitancy problem is worse among younger patients. Seventy-three percent of Americans over the age of 18 have gotten at least one dose of vaccine, but in the three months since the FDA expanded vaccine eligibility to include people ages 12 to 16, only around a third of kids between 12 and 17 have received their first dose.

“We hit a wall,” Offit said of low youth vax uptake. “Question is why [parents] said, ‘No thanks.’ I hope the reason they said ‘no thanks’ is because the vaccine hadn’t been approved.” If that’s the case, full licensure of the Pfizer jab might actually drive an increase in kids getting vaxed.

Low vax rates among children is especially vexing as schools reopen and tens of millions of students pack hallways and classrooms. Some schools have mask mandates. Many don’t or, in some Republican-governed states, legally can’t.

While younger Americans are far less likely to die of COVID than older Americans, more and more kids are catching non-fatal infections as the new Delta variant drives up overall case rates. In hard-hit Florida, the seven-day average of new cases in kids under 12 grew sevenfold from late June to late July—from around 200 cases to more than 1,500. Doctors were shocked at the number of kids landing in the hospital with serious infections.

The FDA is trying to head off the looming crisis. Experts anticipate that, as early as this winter, the feds will open up vaccine eligibility to include kids under 12. But eligibility alone doesn’t guarantee uptake, as the low vax rate among 12-to-16-year-olds indicates. “If you take a lesson from the fact that two-thirds of adolescents are not vaccinated, parents aren’t going to rush to get under-12s vaxed, either,” Offit said.

Maybe full licensure of the Pfizer jab will do the trick, and boost confidence among the most hesitant parents in the weeks before those under 12 become eligible for the vaccine. Maybe we’re on the cusp of a big surge in vaccine uptake that will make the coming school year a lot safer.

Or maybe not. Offit for one is trying to manage his expectations. There’s a good chance full FDA authorization won’t make a big dent in vaccine hesitancy, he said. “It would surprise me to think that someone would think, ‘Now it’s safe,’” he said.

It’s sad but true—the combination of full vaccine licensure and expanded eligibility might not solve America’s COVID problem all at once. But every additional shot in an arm is a small step toward herd immunity. If FDA authorization even slightly boosts confidence in the Pfizer vaccine ahead of youths under 12 becoming eligible, it’s part of the overall solution to the big, complex problem of vaccine hesitancy.