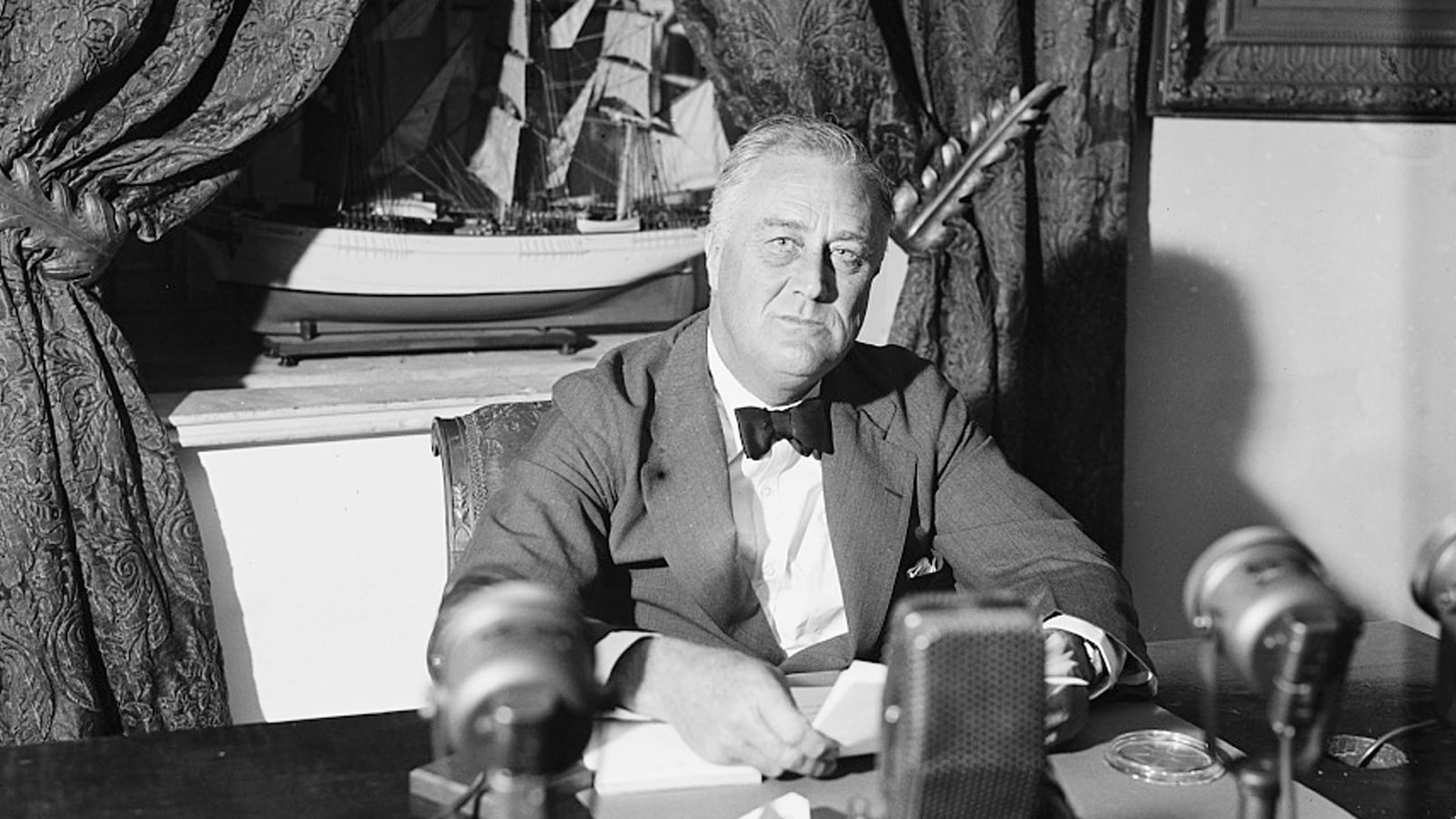

If you look only at the old newsreels and black-and-white photos, it can be hard to understand the secret of FDR’s success.

The paralyzed patrician politico transformed himself into a popular icon by embracing the new technologies of his time and working closely with the press to project himself into the hearts and homes of Depression Era Americans. He became, in the words of one contemporary forgotten man, “the first man in the White House to understand that my boss is a son of a bitch.”

JFK was famously the first president to master television. Barack Obama used the Internet and social media to propel himself to the presidency. But the new technology of FDR’s time was radio. The radio revolution represented an evolutionary leap beyond the telegraph, allowing voices to travel through the air and reach the ears of otherwise remote citizens in their living rooms and local gathering places. And though his presidential predecessor, Herbert Hoover, had pioneered the promotion and regulation of radio, FDR fully grasped the potential of radio as a tool to connect emotionally with Americans in times of crisis.

His Oval Office radio addresses were famously labeled “Fireside Chats” and he called listening citizens “my friends.” His delivery was warm, casual and conversational. FDR wanted to project easy grace rather than stiff formality—especially when communicating complicated matters. The most complicated of matters was the national banking system and the failure that had set off such a national panic that the new administration determined that it must close all banks to assess their strength and solvency. With typical flare, FDR pronounced this nothing more than a “bank holiday”—something breezy and light, rather than the temporary federal freezing of assets, which it was.

His fireside chat announcing the bank holiday during his first days in office remains perhaps unequaled in the long slog of presidents trying to explain financial matters simply and directly without sacrificing detail.

FDR began simply, speaking as he would to a small group of friends rather than falling back to the politician’s typical oratory of the time—essentially shouting to be heard above the crowd. It might seem like a small, obvious thing, but at the time it was a revolution in personal presidential style.

“My friends, I want to talk for a few minutes with the people of the United States about banking,” FDR began, “with the comparatively few who understand the mechanics of banking but more particularly with the overwhelming majority who use banks for the making of deposits and the drawing of checks. I want to tell you what has been done in the last few days, why it was done, and what the next steps are going to be.”

Simplicity was key in FDR’s explanation and he began with the basics.

“First of all let me state the simple fact that when you deposit money in a bank the bank does not put the money into a safe deposit vault. It invests your money in many different forms of credit-bonds, commercial paper, mortgages and many other kinds of loans. In other words, the bank puts your money to work to keep the wheels of industry and of agriculture turning around….”

The next challenge was to explain the panic that necessitated in the bank closures in a way that wouldn’t cause more panic.

“What, then, happened during the last few days of February and the first few days of March? Because of undermined confidence on the part of the public, there was a general rush by a large portion of our population to turn bank deposits into currency or gold. — A rush so great that the soundest banks could not get enough currency to meet the demand. The reason for this was that on the spur of the moment it was, of course, impossible to sell perfectly sound assets of a bank and convert them into cash except at panic prices far below their real value….”

FDR was also careful to frame the unprecedented government action as something common sense and essentially pragmatic.

“I hope you can see from this elemental recital of what your government is doing that there is nothing complex, or radical, in the process…”

He was also honest about potential losses—leveling with the American people rather than promising rosy outcomes that could undercut his credibility.

“I do not promise you that every bank will be reopened or that individual losses will not be suffered, but there will be no losses that possibly could be avoided; and there would have been more and greater losses had we continued to drift…”

Finally, he offered a call to action for the American people rooted in simple confidence—emphasizing that they would solve this problem together rather than simply through presidential action on high. He asked for emotional buy-in and a sense of shared responsibility that could ultimately change the culture.

“After all there is an element in the readjustment of our financial system more important than currency, more important than gold, and that is the confidence of the people. Confidence and courage are the essentials of success in carrying out our plan. You people must have faith; you must not be stampeded by rumors or guesses. Let us unite in banishing fear. We have provided the machinery to restore our financial system; it is up to you to support and make it work. It is your problem no less than it is mine. Together we cannot fail.”

With a shared sense of mission and compelling, clear explanation, the new president was able to put himself and the American people on the same side, committed to solving a common problem.

But mastery of the new medium was not FDR’s only trick. Projecting a happy warrior persona, FDR did not simply try to use the radio as a means to get around the news media to communicate directly with the American people, as subsequent presidents have attempted with the dominant media of their time. Instead, FDR engaged the White House press corps with an extended charm offensive, drawing them close and often acting as a source for their stories. He promised the reporters regular press conferences and exceeded their expectations—conducting 337 in his first term and 374 in his second. FDR would go so far as to suggest story frames and offer off-the-record tips from the highest source in the land.

Flattered by the attention, the press corps returned the favor by quadrupling the amount of Washington coverage in 1934 as they had devoted during the presidency of Herbert Hoover. “Power in the wake of the Depression was waiting to be taken, and Franklin Roosevelt was going to take it, and those in the media were going to be his prime instrument,” wrote David Halberstam in The Powers That Be. “He understood from his Albany days [as Governor of New York] that the very high public official who gives the greatest amount of information can dominate the story, often define the issue in question and thus dominate the government.”

FDR was a performer whose artistry was the portrayal of easy authority. He did not show the heaviness of responsibility. He projected confidence and optimism at a time when the country had neither. He played journalists with precision by seeming to actually enjoy their presence and making their jobs just a bit easier, aided by the cozy confidences of the time (for example, by mutual agreement no photographs were published of Roosevelt in his wheelchair, effectively hiding his disability from the American people). But he broke down barriers by embracing new technology that could close the tyranny of distance and achieved his goals with an easy charm that was at least part an act, a triumph of will as much as disposition. As FDR once told Orson Welles, “You and I are the two best actors in America.”