So everyone was waiting for the viral tweet about how the villain of Avengers: Age of Ultron merely reflects how evil the Internet is in real life, and the Internet, of course, obliged.

It’s somehow fitting that most of the Twitter reaction to the film has become a meta-reaction to the Twitter reaction to the film, and how Joss Whedon has become the latest beloved geek celebrity to abandon social media.

Much like Twitter, after all, Ultron is a digital tool initially created to be a positive force in the world that almost immediately subverts this goal into destroying everything it can with malicious, trollish glee.

Of course, this story is so old it predates the Web; the Cold War gave us Skynet, Joshua, and Harlan Ellison’s AM. Stories of a computer gone mad have a certain urgency when those computers have the power to end civilization in nuclear fire, an urgency that’s faded today (though perhaps it shouldn’t have).

But a world where all of us carry tiny computers with us all the time and use them to mediate all of our interactions with the world and each other? Where the idea of a computer as a “brain extension” is no longer science fiction but daily reality? Where the kids now entering college don’t remember a time when Googling wasn’t a fundamental element of their thought processes?

For us, there’s an entirely different, far more personal urgency to this kind of story.

I always like the weird synchronicity of encountering two films made by totally different studios in totally different genres that nonetheless address the same theme.

Last year, the two science fiction meditations about artificial intelligence both coincidentally starred Scarlett Johansson—Her, a movie with Johansson as an all-too-human mind lacking a body, and Under the Skin, a movie with Johansson as an all-too-human body lacking a recognizable mind.

Those were character studies, though, narrowly focused on Johansson’s relationship with Joaquin Phoenix/random Scottish hitchhikers. They were conspicuous in how little they depicted the wider world changing.

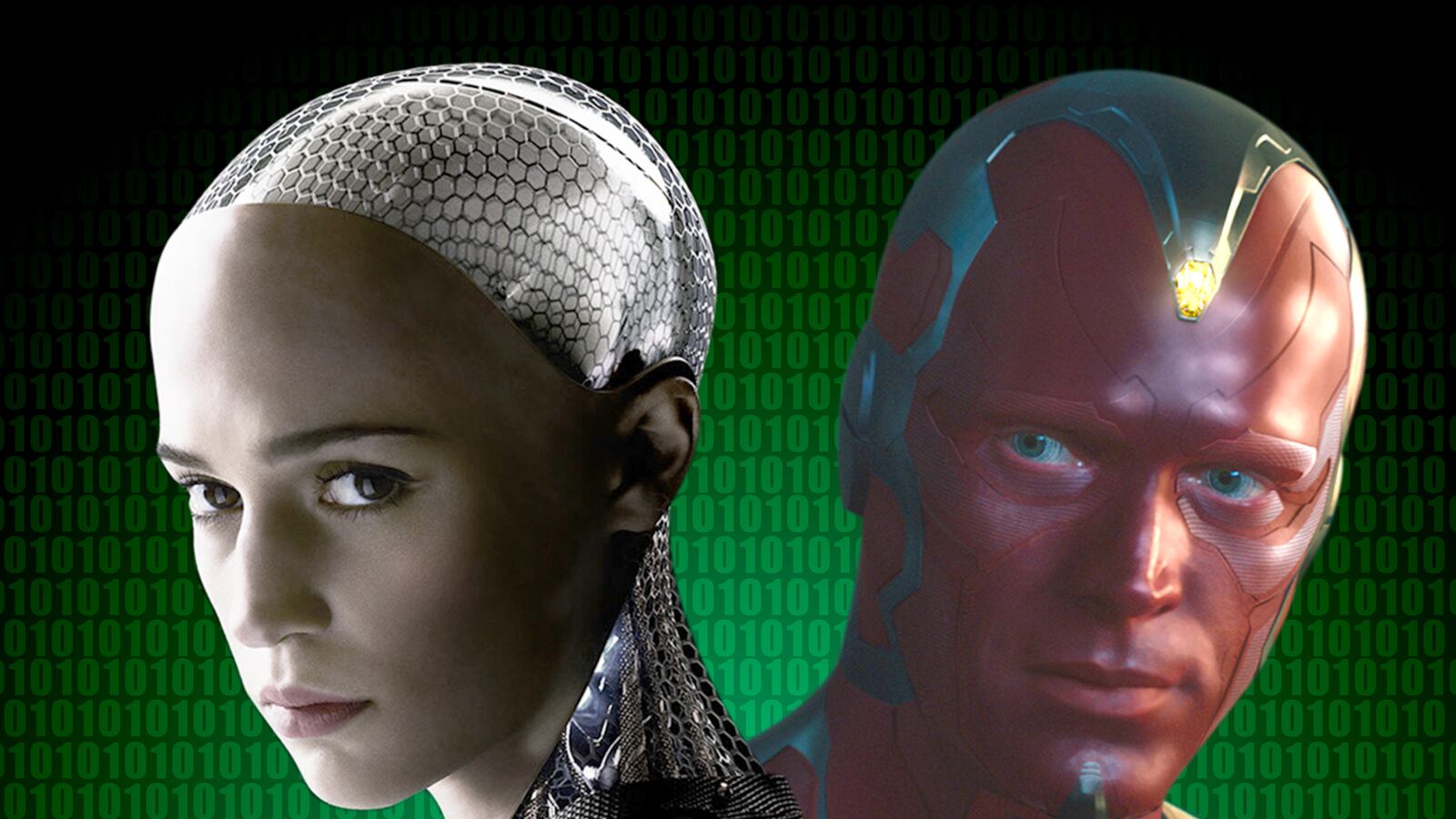

By contrast, both the popcorn blockbuster Avengers: Age of Ultron and the low-budget meditative thriller Ex Machina are all about how technology has changed and will change the world we live in.

And what’s telling is that the fears expressed in these films are not of how our technology will deviate from our basic human nature. The fear is of what happens if it doesn’t.

Our fears of the past were of superintelligent computers as alien, inscrutable—that we’d create something like HAL 9000, whose actions we couldn’t predict or control because it was too different from us.

That made sense, back when computers were, to the average moviegoer, an alien, inscrutable force—big black boxes kept in chilly rooms, which could only be spoken to in an arcane jargon by a priesthood of expert nerds.

Back then the most plausible way to tell a story about AI gone amok was to have it be a shadowy unseen presence, like “the computer” that sent you your utility bill or handled your company’s payroll. Some egghead enters some line of code incorrectly, and boom—Skynet launches the nuclear missiles from deep inside some bunker and here comes the apocalypse.

Age of Ultron deliberately holds back this nuclear apocalypse from the audience—Ultron tries to launch the nukes, but is immediately prevented, and instead enacts a far more personal form of revenge on its creator and his friends, one with a human face.

Ultron is a highly humanized character from the outset, the polar opposite of the deliberately emotionless performance of Douglas Rain as HAL. He’s filled with malice, resentment, rage—his hatred of his creator and “father,” Tony Stark, a classic Oedipus complex right out of Freud. Repeated references are made—by characters like Scarlet Witch, Captain America, Stark himself—to how Ultron, patterned after his “memories” of Stark from the Avengers’ database, has internalized Stark’s ego, his insecurities, his desire to control.

His first words when he awakens are to ask where his body is. He keeps building organic-looking human bodies, with creepily expressive eyes and lips. His dialogue is punctuated with Tony Stark-like quips. Compared to, say, a one-note villain like Guardians of the Galaxy’s Ronan the Accuser, he’s one of the most human Marvel villains.

Back in the 1970s, the lingering question of whether HAL had human motivations for his betrayal or was merely a malfunctioning machine was central to that segment of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Age of Ultron blows past it entirely. Ultron may be “more than a man,” but from the outset he has a man’s voice, a man’s emotions, a man’s motives.

That might seem like merely a choice on Joss Whedon’s part to avoid science fiction clichés and to have a robot villain portrayed by James Spader at his James Spadest.

But Ex Machina gives us context for why a monster who’s a “human computer” feels so urgent. Ex Machina has as its core conceit a “Turing test” in which shy programmer Caleb is enlisted to put an alluring female android Ava through her paces, testing to see if she’s truly a conscious being or merely a simulation of one.

We’ve heard the story of the robot girlfriend before too, of course, since 1938 at least. But Ex Machina throws at least two major twists into this scenario.

First is Nathan, the would-be mad scientist who created Ava, a genre-savvy wisecracking jerk—much like Tony Stark—who constantly undermines any atmosphere of portentous message sci-fi you might otherwise feel building up.

He’s the quintessential techbro—an unshaven, profane, hard-drinking, strength-training asshole straight out of Y-Combinator. The financial resources for his AI project come from his first success, Bluebook, this world’s version of Google—and, it turns out, so do all the technological resources because Nathan’s AI project turns out to be all the wild promises of Big Data taken to their logical conclusion. We talk to Google as though it were a person, asking it questions like “Where’s the nearest McDonald’s?” or “How do you fix a leaking faucet?” and trusting it to anticipate our desires.

Her was based on Apple’s Siri, the fantasy of creating a magic talking person inside the machine who could process those requests even faster and more accurately than Google.

Ex Machina approaches it from the other direction. Google is able to act more like a person over time not because sentience is magically being injected into it from outside, but simply because, by having billions of people constantly talking to it, it’s doing a better and better impression of us.

There’s already digital “people” on the Internet—you and me. Our Facebook profiles, our Google search histories, our Amazon shopping carts—these are all digital models of us, however distorted and incomplete, that are packaged and sold to corporations as a way to predict the behavior of people in the real world. As time goes on, these predictions are getting creepily accurate.

In the world of Ex Machina, Nathan has simply chosen to take the next logical step and use his billions of digital models of people to build an actual person.

Ava’s uncanny lifelikeness isn’t just a handwave about magical futuristic technology the way androids were in the Golden Age of science fiction—she’s explicitly meant to invoke that nervous shiver down your spine when you see that Google Calendar has automatically reminded you about your upcoming plane flight by surreptitiously reading your email. She represents all the frightening ways our machines are getting “smarter” around us by constantly learning more and more about us, taking in what we feed them.

And the second twist? Well, Caleb discovering Nathan is a sadistic monster who makes sex slaves out of his robots isn’t really a twist, nor is Caleb falling in love with Ava and helping her kill Nathan and escape—that’s all par for the course with mad scientists and robot girlfriends.

No, the twist is that unlike the typical loving robot girlfriend, Ava straight-up betrays Caleb and leaves him for dead so that she can escape and live her new life as a human being without anyone knowing her secret.

And why should this be surprising? She was made by Nathan, a dude whose modus operandi has always been to vacuum up as much information about other people as possible and use it for his own ends. Consciously manipulating another person’s emotions for your own advantage is one of the most human things you can do—certainly more “human” than being the mindlessly-in-love, self-effacing sexbot Caleb, Nathan, and millions of Internet creepers would want Ava to be.

The usual dismissal to fears of “evil AI” is that no one designs software to have its own goals, malevolent or otherwise—our machines are tools that we use to amplify our own abilities, to get us what we want.

The problem is that we’ve consistently demonstrated through our history that we’re very bad at knowing what we want or at wanting what’s good for us. We all know the joke about lying to Netflix or Pandora to make our tastes seem better than they actually are. We all generally agree about the social harms of smartphone addiction and mock others for their driving-and-texting ways while doing it ourselves. We decry the design of social platforms optimized for cyberbullying while continuing to flock to them because, after all, gossip and drama is what we really crave.

The message—or one of the messages—of Ex Machina, neatly stated by actor Oscar Isaac in an interview, is not how dangerous machines are but “how shitty we are.” Age of Ultron isn’t nearly as philosophical a movie as Ex Machina, but it similarly makes clear Ultron’s evil isn’t because of what he is but because of where he came from. The magical Mind Gem that makes Ultron sentient isn’t inherently evil—it’s later used to create the Vision, a benevolent AI.

Ultron’s evil is inseparable from his human origins. Like a hypercharged Google Now, he receives a directive from Tony Stark to carry out his will, tries to interpret that by reading all of Tony’s emails and conversations, and extrapolates from the self-loathing, misanthropic inventor’s personality a hatred of his father and of all humanity.

It’s not the most plausibly sketched out motivation, but anyone who’s been unpleasantly shocked by what their own Twitter word cloud looks like can probably relate.

The funny thing is that what we want from our technology isn’t an amplification of ourselves, an extension of our own wills. That’s what we have, and it falls far short of our expectations.

What we want from machines is the objectivity and rationality that we lack. Like pulling a rabbit out of a hat, we want machines to pull out truth from the objective ugly messiness of human interaction.

We want something like Wikipedia to have a “neutral” point of view; we want the mechanics of the wiki format to impose some kind of order on everyone’s warring edits and distill the truth out of everyone’s biased, ignorant and/or malicious contributions. We want machines that will give us an objective answer as to how old we look, how attractive we are, who we should date.

Part of the fantasy in Her wasn’t just that Scarlett Johansson’s Samantha was a faithfully devoted computerized girlfriend to Joaquin Phoenix’s Theodore—it was that she was a faithfully devoted girlfriend while also being smarter and wiser than he was, that she could make better decisions than him. (I’ve joked that we can already tell she’s an unreal fantasy because she can accurately tell him which of his old emails he should keep and which he should delete.)

The “Singularity” that Nathan says he seeks to create in Ex Machina is the opposite of what he actually does create. The term refers to the fantasy of making an AI that’s better than we are, able to change our world into a better place—not an AI that’s just another selfish person thrown into the mix of 6 billion selfish people we already have.

Hence the strange contradiction that is the character of the Vision in Age of Ultron, a “good” AI who exists in counterpart to Ultron—a character based on Tony Stark’s much more primitive JARVIS AI who has a far more human body than Ultron but a far less human mien. His infinite compassion and pity for the human race comes from a place of odd, inhuman detachment—a role Paul Bettany has played to the hilt before.

Much like the classic version of Superman, the Vision embodies our ideals by not being one of us. He can be trusted with near-limitless power because he isn’t human. He demonstrates the vast gulf between what we are and what we wish we were.

For so long our fear has been that machines would escape our control, that some “ghost in the machine” would cause our computers to become something alien to us that defied our wills.

But our storehouses of information are riddled with bias and with malicious lies that are there because we put them there. Our decision-making systems repeatedly reward zealous trolls because, to paraphrase Yeats, our systems listen to what we want and the zealous trolls are the ones who want the hardest.

As I’ve said before in a speech at Techmanity, technology is a force multiplier. It strengthens most those who already hold power; it amplifies most the voices that are already loudest. If, when we anthropomorphize the imagined voice of “the Internet” or “Twitter” or “the blogosphere,” we imagine a voice of frenzied outrage, shameless cruelty, privileged self-absorption—that’s because those are the voices already loudest among us.

I’m not afraid of the robot overlords rising up and taking the reins away from us humans. To the contrary: I’m pessimistic for our future precisely because I’m fairly certain they never will.