By Alaa Latif

SULAYMANIYAH, Iraq — One of the smallest and oldest religions in the world is experiencing a revival in the semi-autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan. The religion has deep Kurdish roots—it was founded by Zoroaster, also known as Zarathustra, who was born in the Kurdish part of Iran 3,500 years ago, and the religion’s sacred book, the Avesta, was written in an ancient language from which the Kurdish language derives.

In this century, however, it is estimated that there are only around 190,000 believers in the world. After Islam became the dominant religion in the region during the 7th century, Zoroastrianism more or less disappeared.

Until—quite possibly—now.

For the first time in over a thousand years, locals in a rural part of Sulaymaniyah province conducted an ancient ceremony on May 1, whereby followers put on a special belt that signifies they are ready to serve the religion and observe its tenets. It would be akin to a baptism in the Christian faith.

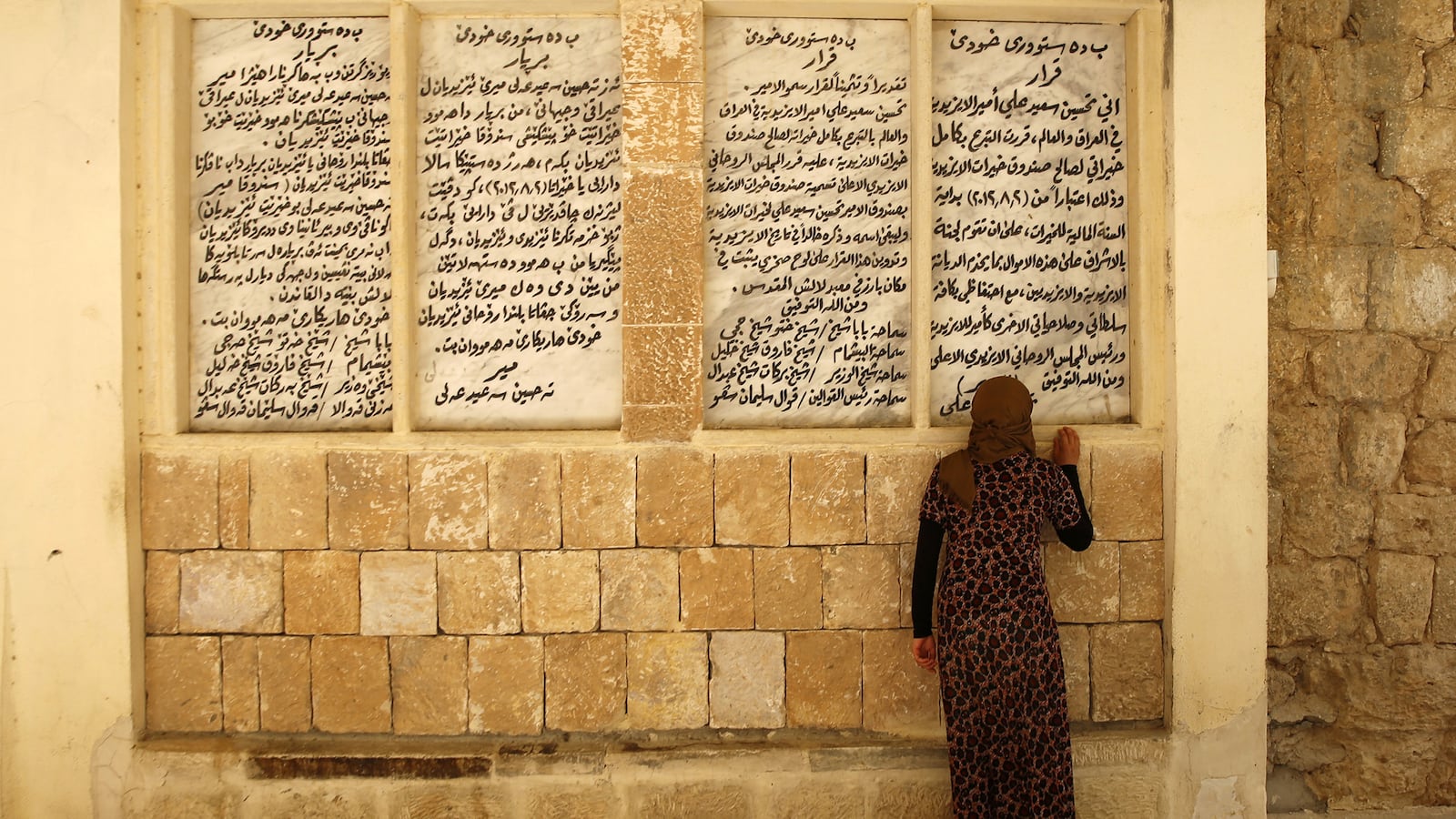

The newly pledged Zoroastrians have said that they will organize similar ceremonies elsewhere in Iraqi Kurdistan and they have also asked permission to build up to 12 temples inside the region, which has its own borders, military, and Parliament.

Zoroastrians are also visiting government departments in Iraqi Kurdistan and they have asked that Zoroastrianism be acknowledged as a religion officially. They even have their own anthem and many locals are attending Zoroastrian events and responding to Zoroastrian organizations and pages on social media.

Although as yet there are no official numbers showing how many Kurdish locals are actually turning to this religion, there is certainly a lot of discussion about it. And those who are already Zoroastrians believe that as soon as locals learn more about the religion, their numbers will increase. They also seem to be selling the idea of Zoroastrianism by saying that it is somehow “more Kurdish” then other religions — certainly an attractive idea in an area where many locals care more about their ethnic identity than religious divisions.

“This religion will restore the real culture and religion of the Kurdish people,” says Luqman al-Haj Karim, a senior representative of Zoroastrianism and head of the Zoroastrian organization, Zand, who believes that his belief system is more “Kurdish” than most. “The revival is a part of a cultural revolution, that gives people new ways to explore peace of mind, harmony and love,” he insists.

In fact, Zoroastrians believe that the forces of good and evil are continually struggling in the world, and this is why many locals also suspect that this religious revival is related to the security crisis caused by the extremist group known as the Islamic State and the deepening sectarian and ethnic divides in Iraq.

“The people of Kurdistan no longer know which Islamic movement, which doctrine or which fatwa they should be believing in,” says Mariwan Naqshbandi, the spokesperson for Iraqi Kurdistan’s Ministry of Religious Affairs. He tell us that the interest in Zoroastrianism is a symptom of the disagreements within Islam and religious instability in the Iraqi Kurdish region, as well as in the country as a whole.

“For many more-liberal or more-nationalist Kurds, the mottos used by the Zoroastrians seem moderate and realistic,” Naqshbandi explains. “There are many people here who are very angry with the Islamic State group and its inhumanity.”

Naqshbandi also confirmed that his Ministry would help the Zoroastrians achieve their goals. The right to freedom of religion and worship was enshrined in Kurdish law and Naqshbandi said that the Zoroastrians would be represented in his offices.

Zoroastrian leader al-Karim isn’t so sure whether it is the Islamic State, or ISIS, that is changing how locals think about religion. “The people of Kurdistan are suffering from a collapsing culture that actually hinders change,” he argues. “It’s illogical to connect Zoroastrianism with the ISIS group. We are simply encouraging a new way of thinking about how to live a better life, the way that Zoroaster told us to.”

On local social media there has been much discussion on this subject. One of the most prevalent questions is this: Will the Kurds abandon Islam altogether in favor of other beliefs?

“We don’t want to be a substitute for any other religion,” al-Karim replies. “We simply want to respond to society’s needs.”

Even if al-Karim doesn’t admit it, it is clear to everyone else that committing to Zoroastrianism would mean abandoning Islam. But even those who want to take on the Zoroastrian “belt” are staying well away from denigrating any other belief system. This may be one reason why, so far, Islamic clergy and Islamic politicians haven’t criticised the Zoroastrians openly.

One local politician, Haji Karwan, an MP for the Islamic Union in Iraqi Kurdistan, tells us he doesn’t think that so many people have actually converted to Zoroastrianism anyway. He also thinks that those promoting the religion are few and far between. “But of course, people are free to choose whatever religion they want to practice,” Karwan told us. “Islam says there’s no compulsion in religion.”

On the other hand, Karwan disagrees with the idea that any religion—let alone Zoroastrianism—is specifically “Kurdish” in nature. Religion came to humanity as a whole, not to any one specific ethnic group, he says.