By Patrick Malone and Peter Cary. This article originally appeared at The Center for Public Integrity.

Consolidating the management of two critical sites where nuclear weapons are assembled would yield huge taxpayer savings, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) promised in 2013—as much as $3.27 billion over a decade.

Hundreds of millions of dollars in savings were to be spent on the modernization of the nuclear weapons production complex, and billions of dollars were to revert to the public treasury. The government was so pleased with the promised benefits that in 2015, it gave one of the department’s highest awards to the 14 sharp-eyed officials who processed the single-contract paperwork.

But four years after the consolidated contract was won by Consolidated Nuclear Security (CNS) LLC, a group of corporations led by Bechtel National Inc., there’s not much to celebrate, government documents and reports show:

In particular, much of the promised quick savings haven’t shown up, while the annual federal costs of running and overseeing the two sites—the Pantex Plant in Texas and the Y-12 site in Tennessee where nuclear weapons are disassembled and modernized—have risen more than 30 percent from nearly $1.85 billion to $2.48 billion. Despite these numbers, the government still awarded the contractor extra profits for cost savings.

As a result, the funds needed to keep these two vital sites operating over the next decade threaten to eat up a sizable chunk of the new money the Trump administration wants to spend upgrading the safety, security and quality of the U.S. nuclear arsenal, and enlarging its size. The cost increase, combined with rising fees for nuclear weapons work and physical modernization needs at other facilities, casts doubt on whether Trump’s ambitious nuclear agenda can be completed.

Workers handle armaments at the Pantex plant in Amarillo, Texas.

PantexAn examination of the contract award by federal auditors also revealed that the evaluation process—which parsed bids from some of the nation’s largest defense contractors—was marked by unusual actions that helped Bechtel’s group win the bid. And a powerful lever to force the Bechtel-led firm to achieve as much savings as possible was quietly removed from the contract last September, making it easier for the firm and its partners to win lucrative contract extensions.

The savings that CNS initially promised were supposed to come from cutting what the corporations and their federal overseers claimed were excess jobs and employee benefits at the Texas and Tennessee sites. But key lawmakers and congressional staff in Washington have said this aim was misguided from the outset, coming as it did just as the Department of Energy was launching, at the Obama administration’s direction, a three-decade-long trillion-dollar weapons modernization program, which would seemingly require many new personnel.

“It raises an interesting question: Did the left hand talk to the right hand?” said Gordon Adams, a former White House national security budget official, about the process.

Many workers at the plants have chafed under the new management approach and complained about its consequences, noting in a confidential staff survey that they feel profit has been prioritized over safety. Those workers have been startled to learn abruptly of lost medical benefits at the same time they say their work has become more dangerous due to staffing vacancies.

Contractors get bonus profits

Bechtel and its partners haven’t suffered serious consequences so far from failing to show they met their promised economies. Instead, they have earned extra federally-paid profits of $74.2 million from mid-2014 through 2016, including $36.9 million in cost savings bonuses.

A spokesman for the consortium, Jason Bohne, said these rewards are fair because the group had made significant progress. “Cost savings are being achieved, validated and reinvested,” he said. He added that the consortium “is meeting or exceeding all key mission-related deliverables and has enhanced the sites’ security posture, decreased safety incidents, and improved the sites’ infrastructure, all while implementing cost savings.”

Similarly, Bechtel spokesman Fred deSousa said “the CNS leadership and site employee teams have worked with NNSA to deliver on the mission by advancing national security … and making operations more efficient amidst changing and growing mission demands since the contract was originally awarded.”

NNSA spokeswoman Lindsay Geisler confirmed that the cost of running the two plants has increased, but said it was due to the expanded nuclear work they are doing and the expense of needed modernization. She said that NNSA is benefiting from “more efficient execution of overhead functions, savings in supply chain and procurements, and through restructured [worker] benefits,” and that the previous arrangement would have been even more costly.

The U.S. nuclear weapons program depends on Y-12, located at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, for the highly enriched uranium components that fuel a nuclear blast. The Energy Department projects that the workload at both plants will climb during the next five years as the arsenal’s modernization ramps up, and a draft of President Trump’s Nuclear Posture Review—leaked to the public on Jan. 11—recommends developing still more nuclear weapons that would inevitably add to the workload at both sites, in addition to the budgets and the bonuses available to contractors.

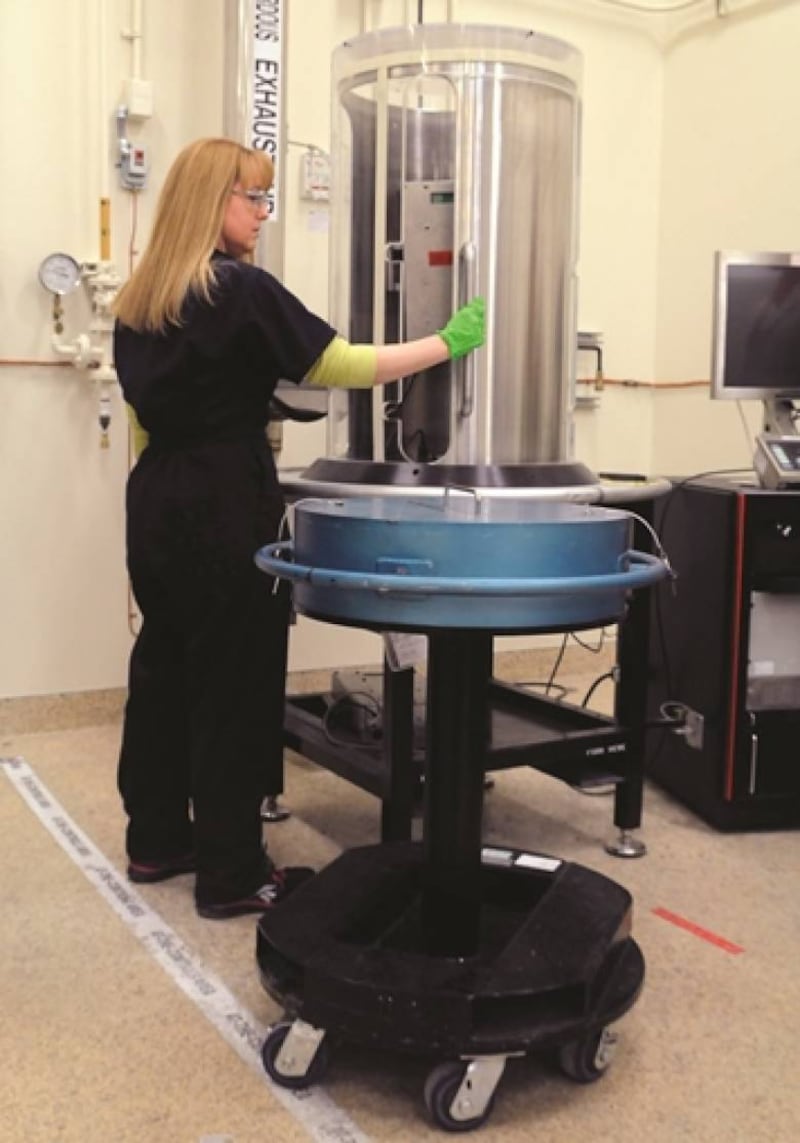

At Pantex’s Special Nuclear Material Component Requalification Facility, pits — a nuclear weapon’s heart — are probed for analytical data.

PantexContracting snafus and cost overruns are not new to the Energy Department, which has been on the Government Accountability Office’s high-risk list for fraud, waste and abuse since the list’s inception in 1990. A 2017 Center for Public Integrity analysis of nuclear weapons contractors’ bonuses over the preceding decade revealed that the firms have received 86 percent of the maximum available to them—$2.6 billion in pure profit—despite these problems, including repeated, avoidable accidents that put workers and sometimes the surrounding populations in jeopardy.

Here’s how CNS got the work at Pantex and Y-12:

For nearly a decade after 2001, the Pantex and Y-12 sites had been run separately by two different management teams headed by Babcock & Wilcox Technical Services Group, under two contracts. In 2010, the National Nuclear Security Administration—which was straining to control costs—decided to explore the potential savings from merging the two sites under one contractor. NNSA hired Chicago-based Navigant Consulting to study the idea, and the firm projected savings of up to $895 million from the more than $22 billion that it would cost to run these sites over ten years.

In December 2011, the NNSA solicited bids for a single entity to run both sites. Bidders were evaluated on several criteria, including the experience of their management personnel and the fees the bidders sought to run the sites. But the solicitation was blunt: “One of the principal purposes of this consolidation is to realize cost savings.”

Revising the bid evaluations

They are all big Washington players, having spent a total of at least $350 million on lobbying about multiple issues in the decade preceding the contract award, according to data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonprofit group.

The fees and savings proposed by the Babcock & Wilcox and the Jacobs-Fluor groups are not known, because the bidding documents are largely redacted. But records show the Bechtel group said it could cut $3.27 billion from the proposed budgets over a decade—three times what the NNSA’s consultant had predicted. Under its proposal, CNS was to be paid special profits if it made this promise come true, amounting to as much as $262.8 million, on top of the $400 million in profits its contract stipulated for good performance.

The Bechtel group’s bid was not a clear winner, initially. According to an April 29, 2013, review of the bidding process by the Government Accountability Office, an audit agency that reports to Congress, a group of Energy Department experts rated the largest portion of the Bechtel group’s proposed savings as “partially reasonable,” but said another part was “not reasonable.” CNS also lagged behind Babcock & Wilcox in internal DOE ratings of corporate experience, project management and key personnel.

The review process was not smooth. During most of 2012, the bid process was overseen by Neile Miller, the NNSA’s deputy administrator. But eight days before the bid decision was to be made, on December 12, she learned she would soon be named acting administrator and handed off the selection responsibility to a deputy, Michael Lempke.

He intervened, upgrading the ratings of all bidders’ proposed savings to “feasible,” and raising the Bechtel group’s grades in other areas where it lagged Babcock & Wilcox, according to the GAO review. That created a two-way tie. Then Lempke ascribed some strengths not noted by other evaluators to the CNS proposal, including organizational structure and experience in consolidating two other Energy Department facilities, the GAO said. The adjustments tipped the scales just enough for CNS to prevail.

A Pantex production technician performs work on a W87 warhead.

PantexThe two losing bidders howled. Their protests went to the GAO, which declared in its review that Lempke hadn’t adequately heeded the “documented contrary conclusions of the agency’s own financial management specialists” that some proposed cost savings may not be feasible. It said the procurement was “flawed” and called for a re-bid.

So the NNSA reopened the bidding process and conducted another review. This time, the Babcock & Wilcox team’s savings plan was officially rated as offering “a significant benefit to the government.” But Lempke had left by then, and his successor raised the Bechtel group’s ratings in three categories, again creating a tie, a later GAO review stated. In the end, the official decided that CNS, the Bechtel group, held the edge and awarded it the contract.

Adams said he found it odd that “all the system [was]…bending towards one contractor twice over,” almost as if “from the beginning Bechtel[‘s team] had to win.” The Babcock & Wilcox team again protested, calling NNSA’s judgments “disparate, unequal and prejudicial.” But the GAO said the Babcock & Wilcox team had failed to show NNSA’s judgments were unreasonable, and denied the protest on February 27, 2014.

But Miller defended the decision, saying that even though CNS’ savings estimates were obviously tailored to meet NNSA’s hopes, the losing Babcock & Wilcox proposal was even more extreme. “From Day One, they were going to be getting rid of people.” She said she was “really taken aback” by that bid.

She also said all bids promising lower costs and higher efficiency need to be taken with a grain of salt. “What are you going to do? Write a bid that says, ‘Given all the political bullshit we won’t be able to meet the savings expectations?’”

Major problems flagged by evaluators

The Bechtel team started jointly running the two sites on July 1, 2014, and was eligible for $20 million in extra profit for good performance in the first year alone. But the NNSA, in its Nov. 2015 report on the group’s performance, said that it would get just $11.4 million. The amount, representing just 57 percent of the potential profit, was considerably less than what NNSA contractors typically receive.

In its review, the NNSA cited numerous failings, including the falsification of site police training records, the repeated placement of the wrong tail cases on B61 nuclear bombs, and a series of maintenance backlogs for the sites’ electrical power systems. The NNSA also said CNS had not developed a consolidated financial system and that without it NNSA could not validate the contractor’ savings claims.

The following year, the contractor did better, earning 77 percent of its performance bonus. But once again NNSA cited a series of production and safety problems. Some programs were as much as 10 months behind schedule. Meanwhile, costs were skyrocketing: Some nuclear bomb work was seeing cost growth as high as 50 percent. Savings claims remained unresolved, “damaging the credibility of the cost savings program,” the NNSA said.

In both its 2015 and 2016 annual evaluations, moreover, the NNSA faulted CNS for staffing shortages in multiple areas—quality assurance, project controls, metal production, radiological protection, and safeguards and security. For instance, the 2015 performance report states that NNSA “is concerned” with staff losses in radiological protection that affect the ability to survey work spaces and monitor radiological work. That fiscal year ended with 42 radiological personnel contaminations at Y-12, the report states.

The 2015 performance review also says a high rate of attrition continues to plague the two sites’ efforts to defend themselves against computer hacking, citing a loss of senior technical personnel and weak planning as “key NNSA management concerns.” In 2016 the NNSA said, these problems persisted with “no plan for program improvement.” In two other areas, related to the quality and modernization of nuclear weapons, the “lack of staffing identified two years ago remains a significant problem,” the NNSA stated, requiring work-arounds to avoid risks of “defects that could delay work, require rework, or result in an escape,” meaning an accident that spilled radioactivity. At the time of the report, in November 2016, only 16 of 42 vacant positions had been filled.

The NNSA’s Nov. 30, 2017, appraisal was more upbeat, stating that the Bechtel group had “met overall cost, schedule, and technical performance requirements of the contract … in the aggregate.” But it also said the group had failed to jointly “track and clearly identify cost savings,” hampering the success of its efforts.

Two weeks later, the Department of Energy’s Inspector General disclosed that the group had asked that year to be exempted from more than $400 million of the total cost savings it had promised to achieve over 10 years. NNSA responded by quietly agreeing not only to lop off $360 million of those required savings—but also to make the remaining savings a “discretionary” issue in annual evaluations rather than a stipulated requirement for each year of the contract’s life, according to the Inspector General’s report.

It loosened, in short, the conditions under which the Bechtel group can win a contract extension. The modification “allows NNSA discretion in assessing what CNS has achieved in cost savings as compared to mission performance,” CNS spokesman Jason Bohne confirmed.

The Bechtel group, according to the report, had also asked to be paid extra profits for not filling 270 positions that were empty when it started work. But the NNSA declined, saying the group had not done anything to produce these savings. CNS countered that it might then hire the 270 and fire them, according to a negotiation file cited in the IG’s report. (A spokesman for the Bechtel group, in response to a query from CPI, said this was a “hypothetical example.”) So NNSA relented. It agreed to give CNS, the Bechtel group, credit for $68 million in cost savings and to pay the contractor a bonus of $21 million in both 2015 and 2016 for “eliminating” these empty positions.

The group also claimed it had achieved another $92.5 million in cost savings, but NNSA said the amount was actually $44.3 million, only 16 percent of the $272.8 million it had contractually promised to save through 2016. However, NNSA gave the Bechtel-led group credit for sustaining $121.3 million in “prior-year cost savings,” and in the end gave the group a healthy bonus for its cost savings work.

NNSA did not respond to a question about why it took the pressure off such a key contractor. “NNSA is in the process of performing the requisite analysis of savings achieved through the first three years of performance, and therefore, it would be premature to discuss savings achieved to date and whether or not the contract will be extended,” said NNSA spokeswoman Geisler.

“CNS generated significant verified savings to the NNSA for Fiscal Years 2014 through 2016,” NNSA spokeswoman Geisler said in an email. “Verification of Fiscal Year 2017 savings is currently under review.”

In their conversations with the Inspector General auditors, NNSA officials agreed that CNS is behind on delivering promised savings, but expressed optimism that the group will find more or new ways to cut costs in the future. The contract itself had predicted the opposite—that the highest savings would occur at the outset.

Workers complain about turmoil and safety risks

Asked by the IG if the job cutting had had harmful effects, NNSA responded that it did not see a direct link between staffing shortages and any issues at the plant. But the Center for Public Integrity’s reporting, the NNSA’s own records, and a survey commissioned by the contractor in 2015 suggest otherwise.

In early 2016, the Bechtel team announced it would hire 1,150 people at both sites over 19 months. But the actual number at Y-12 and Pantex grew only 2 percent between the end of fiscal year 2014 and the close of fiscal year 2016, according to the Energy Department, because the team also let 1,304 people go in that period. A significant portion of those hired were managers, not line workers.

Workers have grown disgruntled at the turmoil created by the new operating arrangement, including the loss of the unfilled job slots, the uneven hiring, the difficulty of filling some specialized positions, buyouts and terminations of older workers, and the arrival of workers with little experience.

CPI interviewed six current and former Pantex workers about the new management, including one who said a common joke at the plant is that CNS stands for “cut and slash.” Even as late as last month (January 2018) shortages existed, she said. The plant-wide maintenance department was short 14 electricians, yet the contractor had hired six or seven managers instead, she said. “There’s more managers than there are electricians doing the work. It’s messed up,” she said.

She said the site’s facility for sampling, testing, and replacing a gas that boosts the explosive force of nuclear detonations should have seven workers but only has four. The stress caused by overwork could lead to an accident, the worker warned.

Others complained of poor maintenance of the plant’s buildings. “They don’t have the personnel—they’re not replacing personnel,” one worker said. “You’re just hoping to operate and operate safely. You’re just hoping things don’t go wrong.” A former supervisor complained about the loss of benefits: “The quality of life is going down,” he said. “This is not like working at Walmart, this is serious stuff.”

Asked for comment about these worker complaints, CNS spokesman Bohne said the group was spending some of the extra funds in its budget to “provide safe, modern, and efficient work spaces” for more employees. He also said, “the safety of our workforce and of the public is our number one concern.”

But the concerns expressed to CPI were echoed in a 2015 worker survey about the contractor’s safety practices, after the group had run the sites for about a year. “Decisions and behaviors of [contractor] leaders lead the workforce to believe that cost savings and production take precedence over safety,” said the report, which the Center for Public Integrity obtained under the Freedom of Information Act.

Workers resented that the Bechtel group was given extra profits for slashing costs, the report said. It told the group to “emphasize [instead] how cost savings will be re-invested in quality of life initiatives for the workforce.”

Regarding benefit cuts, Bohne said they were needed to better align them “with comparable benefit plans of similar organizations in similar industries.” He said the government had not awarded the consortium extra profits simply for cutting benefits, and that all benefit cuts “are reviewed to ensure that changes will not degrade safety, security, or quality.”

The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit investigative news organization in Washington, D.C.