I once had dinner with the great screenwriter Bo Goldman, who died this week. Bo’s oldest daughter Mia is an old friend of mine, so one night in the late ’70s, while I was still in college, I was invited to join her and her dad at the Café des Artistes. Bo had just won an Oscar for his work on One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. (He would win his second for Melvin and Howard).

My impression back in the day—and my memory now—is that dinner with Bo was somehow like playing in a sandbox with the smartest child you’ve ever met. Which is to say he was both brilliant and somehow childlike in the best sense. He had the innocence that is necessary for an artist. As Martin Amis once put it, artists ask, “Why this?” and “Why not that?”

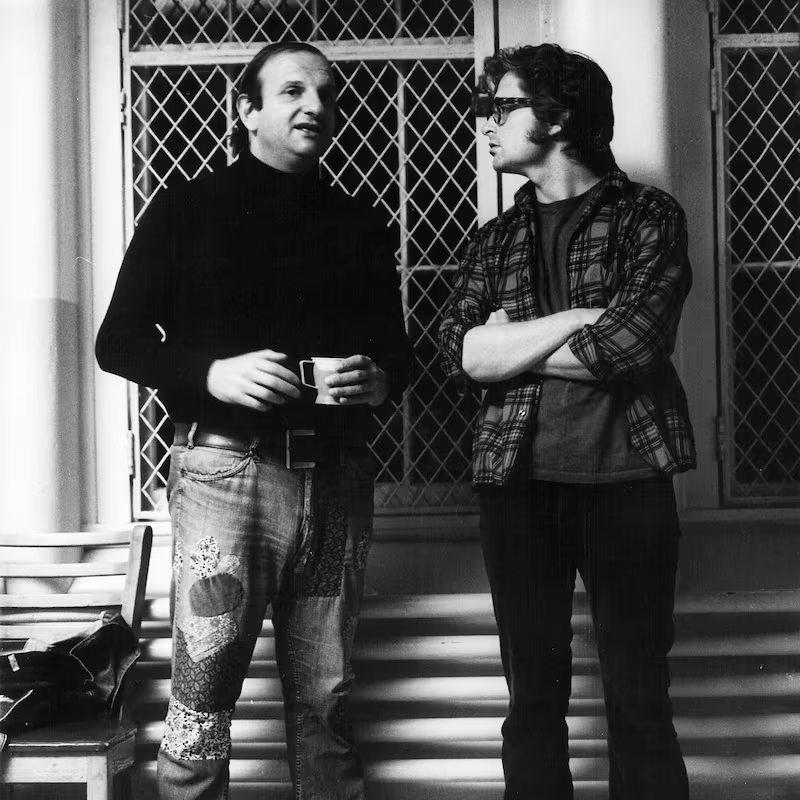

Bo Goldman (left) and Michael Douglas on the set of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in 1975.

Public DomainBo always spoke of himself as a “filmmaker” rather than a screenwriter, and his work challenged accepted ideas of what a movie could be. His films were wittier, more knowing, more sophisticated, more deeply entertaining, and thus more exciting than the work of almost any other writer of his generation. And they were filled with great lines. From Melvin and Howard: “We’re not poor. Broke maybe, but not poor.”

When the film’s anti-hero, Melvin Dummar, who claimed to be the beneficiary of Howard Hughes’ will, tries to force his wife to leave her job in a strip joint, she tells him she can’t quit because “I love to dance.” Only a writer like Bo who struggled to make it in show business until middle age could write lines like that, only a writer who held onto the anger and innocence he needed for his art.

Bo’s greatest film in my view is Shoot the Moon. It was also his first screenplay, and it became his calling card to Hollywood, though it took years to get produced. It tells the story of a divorce between a writer (Albert Finney) and his wife (Diane Keaton). Bo beautifully captures the raw emotions of the couple, but also the ways in which the divorce wounds their children. (Bo had six kids, one of whom, Jesse, died in a motorcycle accident.) And it’s safe to say that no filmmaker ever wrote about children better than Bo. He understood their innocence.

In 1980, I produced Bo’s appearance on The Dick Cavett Show. Speaking about his time at Princeton, Bo, who grew up the son of a once-wealthy retail magnate, said, “I always had a bit too much of the street in me. But in my case, that street was Park Avenue.”

Barbie and Oppenheimer doubtless have their appeal, but I can think of no finer way to spend two hours staring at a screen this weekend than watching one of the great films of Bo Goldman. They are the work of a genuine artist.