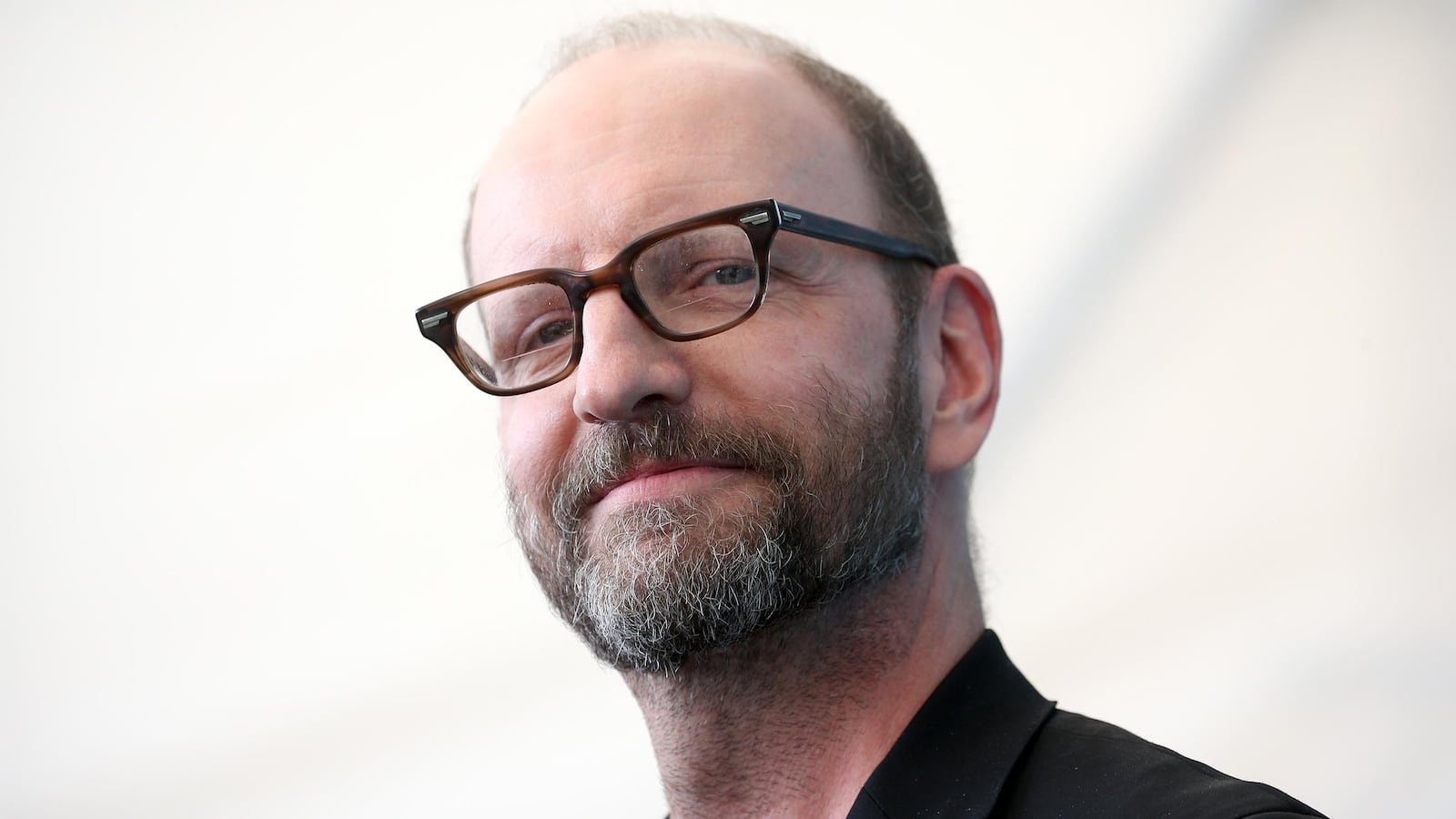

Steven Soderbergh remains American cinema’s most exciting pioneer. From his groundbreaking indie debut sex, lies, and videotape, to his Oscar-winning Traffic and Erin Brockovich, to his blockbuster Ocean’s 11 trilogy, to his more unconventional efforts like Kafka, Bubble, The Girlfriend Experience and Unsane—not to mention his forays into TV with Cinemax’s stellar The Knick, and his inventive branching-narrative project Mosaic—the 57-year-old auteur never rests on his laurels, finding new and unexpected ways to push himself and the medium, all while maintaining his signature, electrifying flair and incisiveness.

On the heels of last year’s one-two Netflix punch of High Flying Bird and The Laundromat, Soderbergh returns to the streaming world this week (Dec. 10) with Let Them All Talk, a jazzy, semi-improvised drama for HBO Max—with whom he’s signed a wide-ranging production deal—that stars Meryl Streep as a celebrated author who attempts to reconnect with her two college friends (Candice Bergen, Dianne Wiest) by taking them on a New York-to-London cruise aboard the Queen Mary 2 to attend an awards gala. Also featuring Lucas Hedges and Gemma Chan, it’s a simultaneously breezy and profound (as well as intriguingly ambiguous) story about communication, art, and betrayal, and it proves another triumph for the director.

With Warner Bros. recently announcing that its entire 2021 movie slate will premiere on HBO Max, Let Them All Talk arrives at a moment of potentially historic industry change, and that was one of the many topics we discussed with Soderbergh during our wide-ranging chat ahead of his latest’s debut—a conversation that also touched on everything from filming on a cruise ship pre-pandemic, to collaborating with Streep, to re-editing some of his earliest gems.

First, I have to ask: were you one of the 14 lucky individuals who received $1 million from George Clooney?

[laughs] No. Much to my dismay, I did not make the cut.

Did you have words with him about it?

No. When I heard about this, I knew that this was a very tight circle of George’s, and I didn’t really meet the criteria for it. But I thought it was an incredibly kind gesture—not uncharacteristic of George, who’s incredibly generous and loyal, and the world’s best host. I’m sure it was an incredible evening.

Any plans to reunite with George on a new movie?

We’re still in regular touch, and talk about trying to find something to do that would allow us to work together again, but would also be something unlike anything we’ve done before together. We’ll figure that out.

It feels like a lot of people have been revisiting Ocean’s 11 during quarantine. What do you make of the film’s enduring popularity?

I don’t know what to attribute that to. It’s certainly unusual that we were able to keep that entire cast together and make three films in six years. That’s hard to do, just in terms of cat herding. And that’s all Jerry Weintraub’s doing. I think the first one just felt like the planets aligned in a really positive way, in every direction, and it resulted in a good version of what we all imagined a Hollywood movie should be. If you could conjure that at will, you would do so. You never know, but that one certainly felt like we had all the elements we needed to come up with something really enjoyable and satisfying for an audience. When you can do that and also be smart, then you’ve hit the jackpot creatively.

The industry has appeared headed toward a streaming world for some time, and COVID has sped up that transition—highlighted by the recent announcement that Warner Bros. will debut its entire 2021 film slate on HBO Max. Is this the beginning of the end for theaters?

No. Not at all. It’s just a reaction to an economic reality that I think everybody is going to have to acknowledge pretty soon, which is that even with a vaccine, the theatrical movie business won’t be robust enough in 2021 to justify the amount of P&A you need to spend to put a movie into wide release. There’s no scenario in which a theater that is 50 percent full, or at least can’t be made 100 percent full, is a viable paradigm to put out a movie in. But that will change. We will reach a point where anybody who wants to go to a movie will feel safe going to a movie.

I think somebody sat down and did a very clear-eyed analysis of what COVID is going to do in the next year, even with a potential vaccine, and said, I don’t see this as being workable in 2021. Because let’s be clear: there is no bonanza in the entertainment industry that is the equivalent of a movie that grosses a billion dollars or more theatrically. That is the holy grail. So the theatrical business is not going away. There are too many companies that have invested too much money in the prospect of putting out a movie that blows up in theaters—there’s nothing like it. It’s all going to come back. But I think Warners is saying: not as soon as you think.

Are you worried that once the genie is out of the bottle, it’ll be difficult to put it back in?

No. I think it’ll finally push the studios and NATO (National Association of Theater Owners) to have some practical and realistic conversations about windowing. Because there needs to be more fluidity. There’s not going to be one template that fits every movie. Every movie is different. You need the flexibility. If you’re in a bad situation, and you’ve got a movie that you opened wide, and you know Friday at 3 p.m. it’s not working, you need to be able to get it on a platform as soon as possible. You spent so much money trying to make this work, and if it didn’t, you should be able to do whatever you want to do. Theaters are going to be pushing you out anyway because you bombed. They’re looking for the next thing that’s going to work. I just think we live in a technological world that allows for fluidity that we’re just not seeing right now. We’re still seeing this broad template that’s supposed to work for everything, and that’s not how it’s going to get solved.

Will theaters wind up being only the domain of big-budget spectaculars?

I think there are a lot of factors to consider when wondering if that’s the way things are going to go. One variable that hasn’t really been scaled up is that, now that we live in an all-digital world, all of these big theater chains have the ability to turn themselves into repertory cinemas in which they screen films from any period of the last 120 years for audiences who’ve never seen them in a theater. There are all these movies from the ‘70s, ‘80s, ‘90s, and early aughts that nobody has seen in a theater. Big hits, great movies. And I’m waiting for somebody to go, OK, we’re going to have a program where everybody knows that on these certain nights, or on the weekend, you put [them] out. When I was growing up, the repertory cinema had the calendar for the fall, and you would know, oh, they’re going to show Deliverance, they’re going to show this. There are options here to get people back into the habit of going to see movies, and giving them something they’ve haven’t seen before, that aren’t being explored at any sizeable scale. So that’s one thing.

The other thing is, every time we think that it’s just going to be tentpoles and blockbusters—and art-house movies on the other end—something shows up in the middle and works. Downton Abbey made a lot of money. That movie was coming out when we were in discussions with Warners about Let Them All Talk, and I pointed to that as an example of what I consider to be our audience. That’s our demographic; that’s the audience I want. And look, they showed up for that.

Absolutely. But it does feel like more mid-range movies—including Let Them All Talk—are now heading to streaming platforms.

It’s economics. The cost of putting something out is rising faster than the revenue on the return. And it’s a trajectory that nobody’s happy about and nobody can seem to stop. The competition for eyeballs now is really fucking intense. There are a lot of people spending a lot of money to get eyeballs. For the studios, fifteen years ago, they didn’t have to compete with Netflix and Disney+ or whatever. So your marketing dollar went a longer way than it does now, because you spend a dollar now, and everybody else is spending the same amount, including some people that didn’t exist before.

Earlier this year, you signed a production deal with HBO Max. What drew you to that arrangement?

It was a combination of things. I felt a real kinship with Sarah Aubrey, who was running point on the Let Them All Talk negotiations. We quickly fell into a discussion about a larger relationship. What I liked about the scenario was: a) it’s a studio I have a history with, and b) they have a lot of different outlets for things. As someone who has a variety of projects going, either for myself to direct or as a producer, the range of potential homes that the WarnerMedia empire provides was very appealing.

Also, the kinds of movies I tend to make, and that I’m interested in making over the next couple of years, seem to fit right into what a streaming platform wants most, which is, hopefully, smart good movies with movie stars in them. That’s what they want, and I’m like, look, that is a train that I am happy to jump on. Because that’s what I’m most interested in. If you look at everything I’ve done since Che, it’s been a genre film. That’s what I want to do—smart genre stuff, with actors that people like playing the leads. I just want people to watch the stuff.

Lucas Hedges and Meryl Streep in Let Them All Talk

Peter Andrews/HBO MaxHow did Let Them All Talk come about?

It was actually an idea from 12 years ago that Greg Jacobs and I were kicking around while we were finishing The Girlfriend Experience. We were interested in doing another film in that style of highly structured improvisation, but maybe with professional actors this time instead of non-professional actors. We’d come up with this idea of these women of a certain age who go on a boat together. At that point, I think we were thinking of a more traditional kind of cruise. We talked about it a bit and had some basic ideas, and then we tabled it because other things presented themselves. I forgot about it, and when we were finishing The Laundromat, Greg said that maybe we should ask Meryl if she’d be interested in that idea that we’d talked about years ago. I thought that was a great idea.

So I emailed Meryl and said, look, we have this idea, here’s how it would be done—is this something that would appeal to you? She said yes, and then Greg said, I think we should call Cunard, and try to get on the Queen Mary 2, and shoot on a crossing. He called them and we told them the basic idea and that we had Meryl, and they said yes. It was at that stage that it got serious. When Greg asked who should write this, I said, it’s funny, I’ve been thinking about Deborah Eisenberg. I’m such a huge fan of her work, and I don’t know why, but I felt that this reminds me of her stories. I didn’t know her, so I reached out and asked if this interested her at all, and she said, “Anything is better than me having to face a blank page and come up with prose.” We met and I described it to her and she said, sounds great, and she started in. This was March, and we were shooting in August, so it all came together very quickly.

Did you ever imagine the film might become a document of the last gasp of the cruise world?

What was weird was, it kind of felt like that even when we were doing it. Then, when the pandemic took flight, I thought, wow, we just turned into a period film, literally. Like, this is the before-times. I was really curious to see if it would be accepted on those terms, or if that would be a problem, and I guess we’ll find out.

Steven Soderbergh and the Ocean's Thirteen gang at the Palais des Festivals during the 60th International Cannes Film Festival on May 24, 2007, in Cannes, France.

Sean Gallup/GettyHow did filming on the cruise ship work?

All that ship does is go back and forth. There’s no stopping it. So we had the script, we’d toured the boat multiple times, and we’d broken out where we needed to be on the ship, at what point, every day, and they did a great job of coordinating our movements. The passengers were encouraged to sign up as background, and we had a pretty good turnout of very cooperative people on the ship because they felt it was a fun new thing. So other than the fact that we had to generate a lot of material quickly, it was really fun.

Did it pose any logistical challenges?

I never felt constrained. It’s a really stunning engineering achievement, this ship. This is not a case where you see it on screen and it looks great, and when you go on the ship in real life, it’s not as great. It’s as good as it looks. The Cunard people are very, very serious about this. I would come home from the editing room on board, back to my room at 2am, and there were cleaning crews everywhere. They’re obsessive. I would love to do it again and have a project to do—write a script, or edit something. That would be a great way to work and relax. Because in this case, I didn’t really get to enjoy the trip.

Was part of your motivation that you wanted to make a film led by great older actresses, who rarely get to headline Hollywood projects?

What I thought was worth attempting was a story about these three women, and these two younger characters, in which everybody is given their dignity, and nobody’s making jokes about feeling stiff or what pills they’re on. There’s no diminution of their status in life, and being this age. And also, I feel like I don’t often see—and maybe I’m not looking in the right places, but movies in which these generations are communicating sincerely and respectfully, again without devolving into caricatures or tropes. To see Lucas and Gemma engage with these women at absolute eye level—that’s what I’m happiest with about the film, is watching these generations speak candidly and sincerely to each other.

The issue of communication seems to be at the heart of the film, and in Meryl’s big lecture, she talks about how her own consciousness connected with that of her favorite author. Is Let Them All Talk about how the movies connect with us, in this invisible but profound manner?

Storytelling is a form of time travel, and I think that’s the idea Deborah and I were chasing. That lecture, Deborah wrote it out—Meryl didn’t improvise that. There are multiple situations in the movie in which we had scenes that Deborah and I felt were too critical to be left to improvisation, where something very, very specific needed to be achieved, and it’s not fair to burden the actor with what is essentially a real writing moment. That was one of them. Deborah wrote this great imaginary lecture where you’ve got one fictional character talking about another fictional character, and how they connect. I thought it was really elegant.

How much was improvised?

The problem is the “I” word creates a very negative reaction in the minds of the audience; they’re taking it less seriously, because they imagine the bad version of something improvised. We’ve all seen that. So I would put the ratio at about 70-30, in terms of improv versus scripted dialogue. Now that is on top of the fact that we had a 50-page script that described scenes and everything that’s discussed in those scenes in a lot of detail. What I was giving the actors the room to do was to speak as that character. But the three bullet points of a scene they knew they had to discuss.

Was there a particular reason you went that route?

Yes. If you’re rigorous about it, you can get some really interesting stuff happening spontaneously. I would argue that, if you go back and watch the film with this in mind, there’s a quality to the way people listen when they don’t know what’s coming that is very compelling. I’m setting up situations where the actors feel safe, they know nothing bad is going to happen to them, but they really don’t know what the other person is going to say, and they have to pay attention. I’m playing as often, or more often, on the person who’s not talking as I am on the person who is talking because I love watching them, in real time, try to navigate what they’re being told. That’s what you’re chasing—those moments where you get a reaction or somebody’s saying something that’s so true, it pins you.

Dianne Wiest’s character Susan says that, regardless of technology, human communication basically remains the same because humans are fundamentally the same. Do you agree?

I could argue both sides of that. That’s one take, and you’d have to ask Dianne if she’s speaking as Susan or if she’s speaking as Dianne. She made that up. But I think I could argue both. My concern, and Tyler’s concern in the movie, is whether technology is allowing the destructive aspects of our personalities to move at a faster rate than ever before, and have we lost our ability to rein it back in. But she’s right that people are people; it’s not like we’ve changed. It’s just the extreme connectivity and freedom of moving ideas around has resulted in a doubling down on the empirical fact that destructive ideas move faster, and create disproportionate damage, compared to good ideas, which tend to take longer to play out, require the cooperation of a lot of people, and the result is almost a non-result—which is you’re hoping for peace. It’s not as exciting.

I think you’ve just explained social media.

It’s intense. The cliché of, “It takes a year to build a house, it takes 30 seconds to burn it down,” is absolutely true, and this is what we’re seeing on a massive scale.

What sets Meryl Streep apart?

It’s the trifecta of outsized talent, utter and complete fearlessness, and a total lack of vanity. To see that all in one person is intense [laughs]. And really exciting.

How did that collaboration work?

She and I share a desire not to make anything harder than it needs to be. And at times, it needs to be hard. But when it doesn’t need to be hard, it shouldn’t be. Her process is extremely aerodynamic. There’s no calorie burn on anything that doesn’t matter when the camera’s rolling. I tend to believe that as well—that’s a good way to work. So we very quickly fell into a mutually satisfying rhythm, and understanding. It’s just my bad that it took me 29 years to work with her.

Steven Soderbergh and Meryl Streep attend a photocall for the film The Laundromat on September 1, 2019, at the Venice Film Festival in Venice, Italy.

Vincenzo Pinto/AFP/GettyIs trying new things, creatively speaking, an imperative?

Oh yeah, but it’s sort of selfish in the sense that I’m restless, so I have to seek out things that create just the right amount of terror. Because you need a little pocket of fear all the time to keep your eyes wide open and keep yourself alert. There’s always got to be something about it that I feel like, wow, if we don’t execute that aspect, this thing’s not going to work at all. Some people jump out of airplanes. I decide that we can shoot a movie on a live crossing. That’s how I get a rush. I’m looking for that thing. Both of those have aspects that scare people that do them. And that was the case here. That is my version of jumping out of a plane.

Are there other genres you’re still eager to explore?

I think any filmmaker who’s interested in what a camera can do wants to make a musical. At various stages, I’ve been close to getting something done in that realm, and it hasn’t happened. I think almost every director, secretly or not, wants to try it. But you’re standing on the shoulders of some really talented people. I’m dying to see [Steven Spielberg’s] West Side Story. The idea of his gargantuan staging ability, and that material—I cannot wait to see what he’s done with this.

Between that, Hamilton, In the Heights and more, musicals appear to be back in fashion—so now might be your chance.

It’ll be interesting to see how all these projects play out. Hamilton was, I would think, a very big success for Disney+. Hamilton is kind of Haley’s Comet. I don’t think you can really say, because Hamilton is huge, musicals are going to be huge. It’s its own thing: a complete gamechanger and sui generis project. But I’m just saying, anybody who saw the jitterbug sequence from 1941 or the opening of Temple of Doom has thought, I want to see what [Spielberg] does with a full-blown musical. Because clearly, the thing he does better than anybody else—in terms of pure staging—really plays into what works in a musical. I’m sure it’s going to be bananas.

Steven Soderbergh directs Andre Holland in High Flying Bird

NetflixAnd the kind of film that should be seen on a big screen.

When anybody accuses me—because of my whole day-and-date history—of denigrating, or not being supportive of, seeing a movie in a theater, that’s ridiculous. Anybody who makes anything wants to see it on a giant screen, of course. But hoping for that and wishing for it doesn’t make it so, and so the realities are the realities. At this point, I’m really happy with the fact that Let Them All Talk is going to be seen like this, with HBO Max. I think they’re very happy with it. We’re editing No Sudden Move now, which will be the second movie for them, and I’m really happy with that. It’s completely different than Let Them All Talk—it’s a genre film with a lot of great actors.

No Sudden Move sounds like a return to the crime-drama terrain of the Ocean’s movies, and Logan Lucky. What keeps bringing you back to that genre?

There’s nothing in my upbringing that would signal an interest in crime films, other than the fact that I saw a lot of them and thought they were great. It’s great movie material. People who commit crimes are compelling, because most of us don’t do that and wouldn’t do that, so there’s an inherent drama as soon as you start. At the end of the day, all conflict, and all drama, can be reduced to the idea of betrayal. So when you’re in a criminal world, these issues of trust and betrayal become very amplified, and the stakes are large.

During the pandemic, you’ve re-edited three of your prior films: Schizopolis, Full Frontal, and Kafka. Will we see those new versions at some point?

I’m hoping next year to put out a limited-edition box set of the seven titles that have reverted back to me, or that I have some control over. We’ve been remastering them and cleaning them up. Kafka, I’d always wanted to go back in and alter in some radical way—not to make it more palatable, but to make it into something that I felt mitigated what I wasn’t able to fix. Schizopolis and Full Frontal are just shorter, and the rest are as they were. It’ll be a collection of titles that weren’t made for studios, and in the case of Kafka, hasn’t been available for a long, long time.