I’m sitting in the most quintessential Irish pub I’ve ever been in and am enjoying a perfect pint. I wandered in off the street with no idea what to expect. But I’m quickly reassured by the ten years of Guinness Perfect Pour certificates that line the wall and the inviting atmosphere. Even better the Irish Coffee is impeccable. But I’m not in Dublin or at New York’s Dead Rabbit or San Francisco’s Buena Vista Café—I’m actually sitting in, of all places, Osaka, Japan.

I first visited Tokyo two years ago and immediately fell in love with the city. During the course of a week, I crisscrossed the city diving into every little nook and cranny that I could squeeze my 6’5’’ body into. I wanted to soak in as much culture from the trip as I possibly could. And, of course, being a bartender, I wanted to drink at all of Japan’s best bars. I was very much a “bartender abroad” going from establishment to establishment in order to cross each name off my extra-long list of must-see spots.

The influence of the Japanese bartending style on the modern American cocktail movement is undeniable. And its influence on my own personal career, is hard to quantify. I’ve watched hours of Japanese videos online trying to teach myself ice carving techniques and perfect legendary barman Kazuo Uyeda’s signature hard-shake.

But once I was actually in Tokyo something unexpected happened.

I was standing at the door of one of the best bars in the world. I had been politely told that there were no seats at the moment and while they didn’t know when one would be available I was welcome to wait. So, I waited. I read over the list of rules of behavior posted at the entrance. I listened to the snippets of conversation that slipped out of the bar.

After a few minutes, I had a realization: I had been to this bar before. Maybe, not this exact bar but like other great bars I’ve been to, it would have phenomenal drinks and impeccable service but it would be extremely familiar. So, I left.

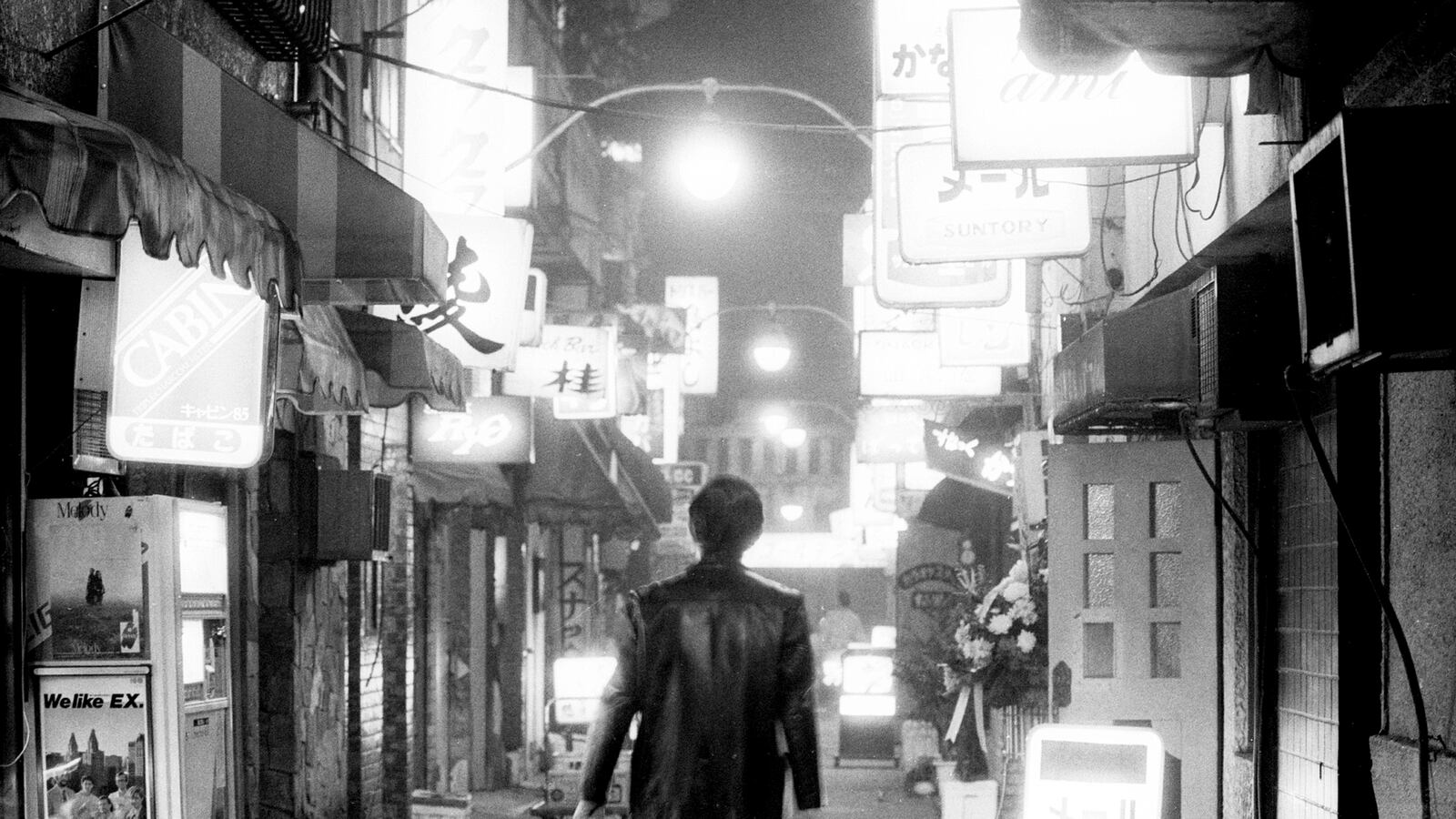

I began to wander aimlessly. I ended up being (politely) refused entrance to a members’ only jazz club before finding a seat at a bar that had no English name. I ordered a Suntory Highball and despite the language barrier the bartender pulled every Suntory product from the back bar to make sure I got the exact Highball I wanted. I then watched the him brûlée half of a passion fruit as a garnish for a single drink and the businessman I was sitting next to bought me a shot of Hibiki 17 because he saw how excited I was to see a bottle of it.

The bartender squeezed fresh juice to order, had better knife skills than many of the chefs that I’ve worked with, and ran an entire bar with just the help of a single barback. There was an attention to detail and a thoughtfulness that I had never seen before coming to Japan. And now I saw it everywhere I went—from the world-famous bars to humble ones.

It was this mindfulness that I brought back to the States with me. It completely changed my perspective. I began to examine not just how I do things but tried to figure out why I do them. It pulled my focus away from the technical aspects of simply making a drink and helped me explore how to improve the entire experience for a guest.

So, when I was in Japan again recently, it was no longer about being a “bartender abroad” and I didn’t try to finish my list of all-star bars. Instead, I looked for another dose of spontaneous inspiration. And because I wasn’t trying so hard to hit every famous bar and landmark, I was actually able to relax and absorb more. There is, of course, an ephemeral quality to life that I think is perfectly captured by food and drink. These are experiences that are by their very nature temporary, yet at the same time immensely impactful because they mean so much to our continued existence. We have to eat and we have to drink. But how we eat, how we drink, and how thoughtful we are about the whole affair makes a world of difference.

Which brings me back to the Irish pub, because there’s always an Irish pub. It wasn’t something I was looking for but was the perfect example of the forethought and hard work that is so often put into improving even the most quotidian of things in Japan. That lesson resonated so strongly with me that I’m now half a world away singing the bar’s praises.

I love Japan because it makes me see myself and the world in a different light. What I will forever strive for is that sense of thoughtfulness and hope that one day someone will love the experience I was able to give them even without knowing my name.